How we can best support our loved ones in their final moments?

How a death doula supports the living, and the dying, at the end of life.

Listen 12:53

Reporter Kerry Sheridan with her grandmother Olga Smith making "Kapusta" or cabbage soup in 2019. (Courtesy of Kerry Sheridan)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

In the last several years of her life, my grandmother, Olga Smith, lived a few miles away from me, in Sarasota, Florida. I called her Meema. About once a week, I’d go pick her up at the assisted living place.

We would go for a drive, and get a milkshake, and just chat. Once, I surprised her by bringing along my recording gear. I steadied the mic in the center console, and hit “record” before she got in the car.

“I’m recording you,” I said, after a few moments, as we drove to a local butcher shop.

“Recording? No!,” she said with a laugh. “You should have told me before!”

That day we were on a mission to recreate a family recipe. A soup that her Ukrainian parents always made. It started with a meaty bone, and included carrots, tomatoes, garlic, dill, and cabbage. I thought it was known as Borscht, but she described it as “Kapusta,” which is the Ukrainian word for cabbage.

“Kapusta, they called it. Cabbage soup,” she said.

Sometimes, Meema would say this hearty, healthy soup was the reason she lived so long. But on this day she also told me they ate it a lot … and it wasn’t her favorite. Sometimes she’d protest.

“Soup again? And my father said, ‘Eat!’ “Cause he loved it, you know?”

My grandma loved to make jokes. She lived a long time, and she seemed to live in the moment. She was fortunate to be in good health for most of her life, walking and swimming almost every day. I never heard her complain about anything.

In March, we celebrated her 100th birthday. All her children and grandchildren were there. We had giant balloons and a big, yellow cake. After we sang happy birthday to her, she clasped her hands together, wielding them above her head in a victory sign, like a champion fighter. How we all laughed. Her sense of humor was as strong as ever.

About two months later, she got sick. The first sign was delirium. The overnight nurse at assisted living said she walked out in the hallway in the middle of the night and cried out for someone to go get her husband down at the tavern, she said he needed help.

Her husband, who was my grandfather, died more than 20 years ago.

Eventually, we learned my grandmother had a urinary tract infection, and that’s what led to the delirium. She was hospitalized, got some antibiotics, and did better for a bit. But then, she declined again, and my mother and I decided hospice care was the best option. It focuses on managing people’s pain and symptoms, to make sure they’re comfortable.

Once she settled back into her room, as she slipped in and out of being awake — I saw her do things that I recognized from my years as a health reporter. She was fumbling a lot with her blanket or sweater.

“That condition is actually called carphology, which is grasping at the bedclothes or floccillation which is grasping at something imaginary,” said Fergus Shanahan, a physician in Cork, Ireland, and the author of a book called “The Language of Illness.”

Years ago, he had proposed a simpler term for it, based on literature.

“You actually go to some of the great writers and thinkers who described what they saw. And Shakespeare was one from 400 years ago and it appears in “Henry V,” the play, the death of Falstaff,” he said.

In Shakespeare, a woman describing Falstaff’s death says, “I saw him fumble with the sheets and play with flowers and smile upon his fingers ends, I knew there was but one way.”

Shanahan suggested we call this the “Henry V sign.”

Doctors, nurses, all recognize this is a common sign that a person is near the end.

I had reported on this a decade ago, but I’d never experienced being at the bedside of someone who was dying.

Now, I was watching my grandmother reach for things that weren’t there, pulling on her sweater and blanket. And I wondered, “Is that the Henry V sign? Are those Falstaff’s hands? Is this the end?”

Sometimes, she would wake up and say with a smile that she just cooked a meal with my dad, who was her son-in-law.

My father died of heart failure five years ago. Again I’d wonder, “Is she delirious from the infection? Or is she being greeted by people on the other side?”

Subscribe to The Pulse

My mom was there, too. All the time. She and my grandma were really close. My mom stepped out for a couple hours one afternoon, for a break and to get some things done.

I was by the bedside, alone. And that’s when my grandmother’s agitation began.

She seemed to be sleeping. Then, all of a sudden, she would cry out, almost shout. I’d never heard her yell before. And she’d grab my hand really hard, and twist my wrist, dig her nails into my palm, until it passed — whatever it was.

I didn’t know what to do. A hospice nurse came in and talked to me about upping her pain medication a bit. I agreed. I didn’t want my grandmother to be in pain.

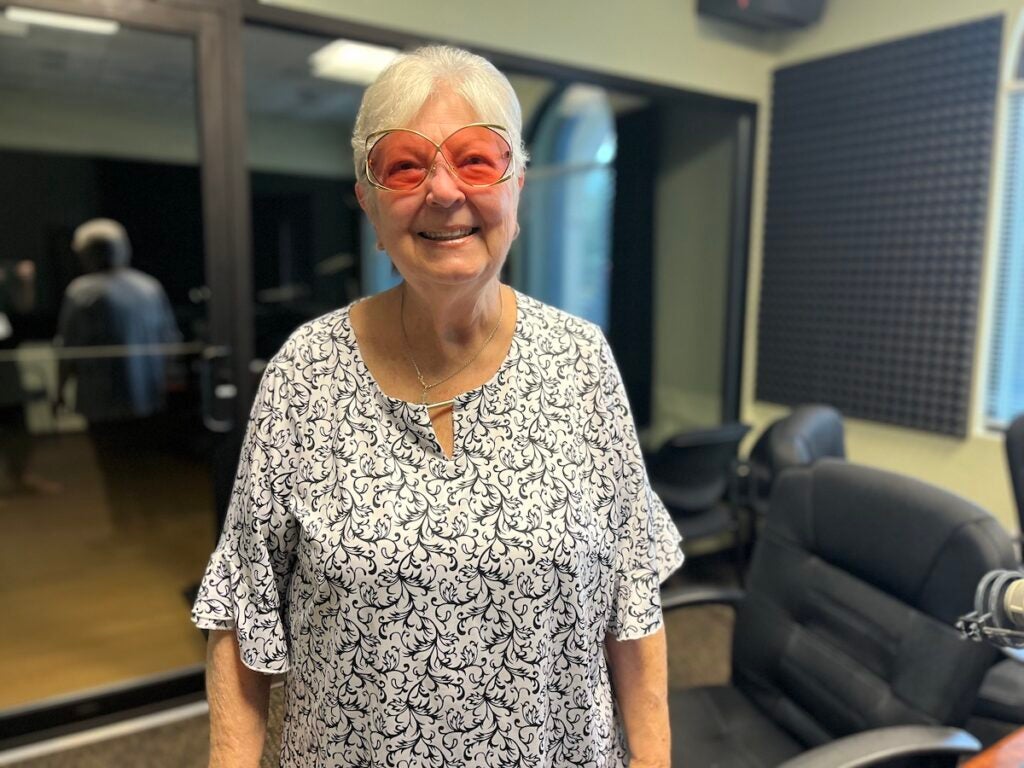

Then in the hallway, a woman appeared. She had short, white hair and wore rose-colored glasses. I didn’t know her, and I didn’t know why she was there. She had a sense of urgency about her. She was an employee of the hospice company, and was there to talk to me.

“My name is Cori,” she told me, waving away the different and much longer name that appeared on her name tag.

She told me she was an end-of-life doula, employed by the hospice company we’d hired, and she was there to help my grandmother and me in any way she could.

Cori told me to stay close to my grandmother. Hold her hand. Talk about fun memories we had. Remind her she’s not alone. Tell her I love her. Anytime I had to step away, make sure that “I love you” is the last thing I say.

She explained that what I was seeing — the occasional visible discomfort, the yelling, it was a natural process. My grandmother was working some things out.

“We have to be respectful and we have to be patient with our loved ones. Because they are fixing their own little issues in a spiritual manner,” Cori said.

“Maybe somebody hurt their feelings when they were younger or older. And in their spiritual mind, because they are already transitioning, they go back to that time and they say you know what? You hurt me. You hurt my feelings. Sometimes the other person might say, ‘I didn’t know I hurt your feelings.’

“‘Yes. Yes you did. So, I want to go in peace. So, I forgive you.’

“Because just as you are fixing all the funeral things and the papers and all the legalities that have to be done, they are fixing their spirit. So don’t rush them. Please don’t rush them,” she said.

Hearing those things was so helpful. Without Cori, coming in at just the right moment, I wouldn’t have known how to be there for my grandmother. And Cori just told me how.

Cori spent some time at my grandmother’s bedside, with me on the opposite side. She spoke softly into Meema’s ear, and rubbed some lavender oil on her hands.

When Cori left, I stayed by Meema’s side, and talked to her about times we walked on the beach together, went out in the boat fishing with my grandfather, how she made that delicious fried fish afterward. I told her to imagine the waves, washing up over her feet and ankles. The sun on her face.

I caught up with Cori later, to talk about that day, and everything that happened.

“When I met you Kerry and you were next to your grandmother … I perceive things. It might be very difficult for you to understand,” she said.

She said the day she came to my grandmother’s room, “I saw this beautiful flow of love going back and forth from Kerry and her grandmother. So, it was a little bit hard for me to understand. There is so much love. Why is Kerry so uptight or so I don’t know, nervous, maybe? Until I explained to her that the love she was giving just being there was the most beautiful gift that anybody could ever receive.”

Truthfully, I had never thought about casting a moment like that in a positive light.

That’s the role of an end-of-life doula. Cori has been working with the dying and their families for decades. At age 78, her work is a product of her training as a cardiac nurse in Mexico, where she grew up, with her faith in God and what she learned from traditional healers in remote villages of Mexico.

Her full name is Laugene Frances Hasbach Wear, but she goes by Cori, a nickname that came from her American mother.

“My parents named me that because my mother had an accent to say sweetheart in Spanish, so she said ‘Ok, Corazon, it’s too long, I’ll just call her Cori.’”

Cori was born in the U.S. Her mom was American, her dad was from Mexico. The family moved to Mexico when Cori was a child.

“I have been a nurse for 60 years and I have never let one of my patients die by themselves. Never,” she said.

That’s the tradition in Mexico. The nurse is there when the patient dies — and afterwards, they wait until the family arrives, she said.

“It is so old-fashioned and respectful. And so sometimes I had to be with a patient 24 hours. Because he was my patient. He died with me. And I couldn’t leave him alone,” she said.

Interacting with villagers near her father’s hometown of Chihuahua, also gave her a deeper understanding. As part of her nursing training in Mexico in the 1960s, she had to visit a lot of very remote towns and villages to provide medical care. She would interact with traditional healers, who were eager to collaborate:

“They’d say, ‘You’re a nurse? So, you teach us things and we will teach you things.’”

“I saw that they used their energy so I said, ‘Explain that to me.’ And they taught me how I could feel my energy, how intense it was and how to make it work better and better, so I learned how to do healing touch, and I learned how to do therapeutic touch.”

Cori told me she has held the hands of all kinds of people as they died. She’s never kept a count. For some, she is the only person there.

“A lot of people can say they are ready for it or they accept their disease, their illness, their sickness — but when the time gets closer everybody says ‘I’m scared.’ And that is when you accompany them all the way,” Cori said.

“When they don’t have a loved one near them, I am the one that takes their hand and holds them tight. And I explain to them: ‘This is going to be a transition, just beautiful. Relax and accept it.’”

Supporting the living, and the dying, at the end of life is a death doula’s key role.

“The whole idea is to renormalize the end of life for everybody. Because it truly is a very natural part of the lifecycle. And the sadness behind that is, is a real part of the lifecycle as well. But the two don’t have to be misery,” said Kris Kington-Barker, director of outreach at the International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA).

INELDA has trained more than 6,000 doulas over the years. And a lot of the work is about translating what is happening to family members.

“If you think about how many times we misinterpret each other just in our daily living, right? How can we not misinterpret people when they’re in their dying too? So, the misinterpretations leave impacts and scars on people’s souls sometimes, and that’s the sad part,” said Kington-Barker.

Interest in death doulas is on the rise but many challenges remain. Hospice often only provides nurses for a couple of hours a week, leaving much work to be done by the family.

And the cost of a doula isn’t paid for by Medicare or most private insurers.

But for those who have access to doula services, the relationship often doesn’t end when the person dies.

My grandmother died peacefully the morning after Cori visited us. My mom was by her side.

Cori said to call her anytime, so a few days later, I did.

“Kerry! Oh I’m so happy to hear from you,” Cori exclaimed, and we both laughed.

And once again, she knew just what to say.

“Remember how I told you, just be so proud of the love you gave to your grandma. It was so beautiful, Kerry. You never let go of her. That’s the beauty of it, Kerry,” she said.

Cori helped me understand that just as the long life of my grandmother was something to celebrate, being there with her at the end was so special, too.

Kerry Sheridan is a public radio reporter in Sarasota, FL. Email: sheridank@wusf.org. Cori Hasbach is a doula in Sarasota, reachable at lhasbach@yahoo.com.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.