How close are we to artificial hearts? New advancements in heart health

Cardiac researcher Sian Harding discusses scientific advances in heart health including growing artificial hearts from stem cells.

Listen 11:51

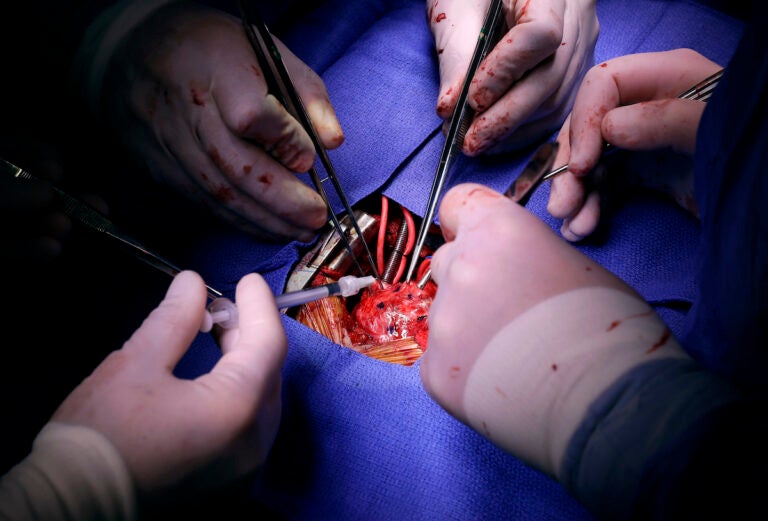

In this Nov. 28, 2016 photo, Dr. Si Pham, bottom left, injects stem cells into Josue Salinas Salgado during open heart surgery at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

To Sian Harding, the heart is a “marvel of construction”. The Emeritus Professor of Cardiac Pharmacology at Imperial College London never ceases to be amazed by this organ and its reliability to keep us going.

“You’ve got three billion heartbeats in a lifetime, 100,000 a day, and you just miss 240 of those, and that’s it,” she said.

In her book, “The Exquisite Machine: The New Science of the Heart,” Harding explores the science behind cardiac care and breaks down the basics of the physical anatomy of the heart, all the way down to our cells.

Harding marvels at how if you separate cardiomyocytes, the individual heart muscle cells, “each one of those will beat like a little heart, beautifully in time.”

However, there are times when the heart doesn’t do what it’s supposed to do, and the perfect coordination of cells gets out of sync. This is called ventricular fibrillation, which prevents the heart from pumping blood. Harding discusses the technological advancements researchers have made in response to conditions like these with devices like an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. This device is made for patients who have already experienced dangerous heart rhythms or “sudden cardiac death” and has the ability to sense irregular heart rhythms and deliver internal shocks to the heart.

Harding spoke with Pulse Host, Maiken Scott, about some of the more advanced research in augmenting the heart through implantable devices, artificial hearts and growing a heart from stem cells.

Interview Highlights

On the challenge of developing an artificial heart

In terms of replacements for the heart, whole artificial hearts [have] been really quite difficult to nail down in terms of engineering. The race for a complete artificial heart was started at the same time as the space race in the 1960s. And you can see what we’ve done with the space race, but whole artificial hearts are still difficult.

The partial artificial hearts, which replaced just part of the lower part of the heart, have been more successful. There are people walking around with those. They started off as a bridge to when you might get a transplant.

On the amount of energy it takes to power the heart

The problem is that it’s the energy required by the heart, the molecule ATP that gives you your energy for the heart and for everything, in fact, is made from glucose. Now, the amount of energy to keep your heart going for one day, if this ATP wasn’t replenished all the time … would be half your body weight of ATP you would need for that.

So it’s just amazing the amount of kinetic energy you need for the heart. And so you need a battery supply outside the body. You can’t get a battery small enough to maintain it.

So you have to have a line through your skin. You have to carry a battery around with you and you have to make sure it’s charged up, obviously. If you think it’s bad for your phone, you obviously don’t want your heart one to go down. So what we’re looking at here is can we do anything in terms of battery technology? And there’s the idea that you might be able to charge up just like you lie your phone on a charger without connecting it. You might be able to have that from outside. So you might be able to charge your device from outside your body. Have a big one of those and lie on it, in fact.

Subscribe to The Pulse

On growing a new heart from stem cells

It’s possible, certainly, to grow cardiac muscle cells from stem cells to turn them into cardiac muscle cells. … Not only can we make stem cells into cardiac cells, we can make many of them, even in my lab which was not a huge lab, we could make billions in a week without problem. They’re also quite good at getting together. If you put them together in a dish they will join up and they will beat like a sheet of muscle. So making large amounts of cardiac muscle is possible, but this is where engineering the heart, you understand how difficult that’s going to be.

So you can inject large numbers of these cells into a heart that’s had a heart attack. …And what happens when … is that eventually after a couple of months they will merge with the heart tissue and they will be fine. But in between that time, between injecting them in and then merging, you’ve got them beating by themselves. You’ve got your heart with one pacemaker and you get these cells that you’ve just injected in — They’ve got another pacemaker. And so the two pacemakers can interfere with each other and produce these kind of dangerous rhythms I’ve been talking about. So getting over that bit and getting them into the heart without disrupting that engineering is our real challenge now.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.