His grandson’s gift strikes a chord with past, helps him tune up physical rehab

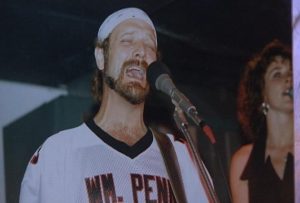

In the 1980s and ’90s, Jimmy Bennett was a regular in the Delaware Valley folk/country music circuit, playing bass or rhythm guitar.

Sometimes referred to as the “New Castle Pirate,” Bennett sang and played at nightclubs, mostly in Delaware. He also played with area folk legend John Flynn at venues such as the renowned Philadelphia Folk Festival.

“We got a big push one year,” Bennett recalled. “We put a band together and we wound up” opening concerts for legends such as Bonnie Raitt, Conway Twitty and Los Lobos.

After taking a full-time firefighting and paramedic job in the late 1990s, Bennett stopped playing gigs. But he often turned to his trusty six-string for relaxation at home.

That all changed in 2012, when Bennett suffered a stroke that left him largely incapacitated on his right side.

He has slowly recovered, but he still uses a cane and has limited use of his right arm — and strum hand.

He tried to play his beloved musical ax periodically, but the attempts proved futile.

“After the stroke, I really missed it,’’ he said. “I picked mine up and found out I have a 45-year-old Guild guitar. Picked it up and tried to play it, couldn’t and cried like a baby.”

Eventually Bennett stopped trying.

William Penn class isn’t your father’s wood shop

This spring, though, a gift from his grandson Andy Walsh turned Bennett’s life around.

The present to his granddad wasn’t something Walsh picked up at a store.

It was something the lanky sophomore built himself at William Penn High School, where he takes construction technology, one of the career pathways at Delaware’s largest secondary school.

William Penn teacher Mac Emerson says his class is not your father’s wood shop as he conducted a tour of his cavernous classroom. It extends outside, where students are framing a large shed.

“Wood shop before was building knickknacks,’’ Emerson said. “Napkin holders. The little roll of paper that you put next to your phone, take notes, and you can pull it down.

“We cover everything from cabinetmaking, framing, siding, custom casework, arbors, custom latticework … to cases, cabinets for the office. Now it’s more career focused, not just going to make a project to take home to mom.”

But Emerson, who fiddles with the guitar, added a music element to his curriculum this past year. It stemmed from a teaching seminar last summer where his group built an electric guitar from a kit.

When he decided to make one for William Penn, his students were delighted.

“They were, ‘I’d really like to do that.’ I was like, ‘Let’s work it out and see if we can get you a kit.’ ”

So two students – Jonathan Magana and Bennett’s grandson Walsh — plunked down $130 for the kits.

The boys spent several weeks assembling the pieces, copiously sanding the body, neck and head, and applying what seemed like endless coats of polish.

“Well, a lot of sanding, a lot. It was to the point where my fingers started to hurt. I had to put on Band-Aids so it wouldn’t rough up my fingers,’’ Magana said.

Magana presented the guitar to his father, who has a renovation business, in May. Fabian Magana is a musical novice, but he said the gift will spur him to learn how to play.

“I’ve done woodworking myself, and I can tell he worked hard at it,’’ the grateful father said. “I’m really surprised. I’m really happy. It’s not something you can buy and give somebody. You build it yourself with your own hands, and that means a lot.”

‘I have to concentrate, and I can’t feel it’

Walsh cherished the opportunity to make the guitar for his musical grandfather.

“I knew he played all the time … when we were little he used to play in the living room while we all watched him,’’ Walsh recalled.

In May, Bennett brought the guitar to school but said he still was struggling to strum and hadn’t played it much. Still, he agreed to try.

The notes he struck were tender and sweet, clear evidence of his talent and experience. But he was obviously frustrated with his inability to really play.

“Can’t do it,’’ he said within a minute.

He tried again, but soon stopped, explaining that his right-hand motor skills were too impaired.

“Where you used to not have to look at the guitar to know where your right hand was or what string it was hitting, now I have to look,’’ he said in exasperation. “I have to concentrate, and I can’t feel it.”

He gave it another try; 30 seconds later, he gave up for good.

“It’s hard. It’s embarrassing because I know what it’s supposed to sound like,’’ Bennett explained.

When a reporter suggested that continuing to practice could help with his stymied rehabilitation, Bennett agreed.

“Absolutely this gives me a reason to. Good reason,’’ he said.

‘Gave him a reason to get practicing again’

In June, at his home in Bear, Bennett was buoyant. It was clear he had been playing. For himself. And for his grandson.

“For him to spend the time he did on that thing, I have to try to play it. I have to,’’ he said, his voice cracking slightly. “He is the reason for all this right now.”

Walsh said he was gratified to see that his guitar had inspired his grandfather to try again.

“I think it just feels good, and I think it gave him a reason to get practicing again.”

Bennett was joined that day by his old bandmate Flynn.

“I think he’s an incredibly talented musician,’’ Flynn said of Bennett. “He’s got the soul and the heart, and that’s as good as anybody for the kind of music I love.”

Then the reunited duo, the legend and his rejuvenated partner, joined in a rousing rendition of a country rock classic, “Me and Bobby McGee,’’ which was written by Kris Kristofferson and popularized by Janis Joplin.

“Feeling good was good enough for me,” the men crooned, their voices and amplified guitars ringing through the house.

“Good enough for me and Bobby McGee.’’

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.