From toilet to tap: Texas town makes the most of its ‘pre-owned’ water

Water shortages forced Big Spring, Texas to begin reusing its wastewater five years ago, but not all locals are on board.

Listen 8:06

The city of Big Spring’s desert-like climate has pushed officials to come up with creative ways to conserve water. In 2013, the Colorado River Municipal Water District opened the nation's first Direct Potable Reuse water treatment plant, in order to recycle the city’s water. (Kristen Cabrera/For WHYY)

Big Spring, Texas doesn’t actually have a spring anymore.

Instead, it gets its water from a handful of man-made lakes — as well as the flushing toilets and draining sinks of locals.

Big Spring became the first U.S. city to adopt a direct potable reuse (DPR) system five years ago amid punishing droughts. The DPR system at the Colorado River Municipal Water District takes treated wastewater from Big Spring, purifies it, and then mixes it with the city’s regular water supply. Eventually, its heads to consumers’ taps.

Some call this system “toilet to tap,” but not University of Southern California environmental Engineer Amy Childress. She prefers the term “showers to flowers.”

Childress says towns used to only worry about how to get rid of wastewater.

“But there’s been a significant change in mindset that now we need to extract the water from that wastewater and reuse it.” she said. “Instead of … looking at how quickly or how efficiently can we discharge the wastewater and send it away, it’s ‘how can we keep it and reuse it?’”

She explains that cities that don’t use DPR are still reusing their wastewater. They just do it in a roundabout way. Wastewater is treated, then dumped into an environmental buffer: a river or lake or underground aquifer. Then, after some time, that water is drawn up and treated again before making it to the taps.

“And the buffer is also talked about as a psychological barrier because it does distract us from where our water comes from — which is a wastewater,” Childress said.

The buffer adds some safety to a water system as well, because treated wastewater doesn’t go immediately back to the taps. If something goes wrong in treatment, engineers have time to fix it before anyone takes a sip.

But Big Spring was losing water to their buffer: surface reservoirs, which are basically man-made lakes.

“Mother nature would take it away from you just as easy as she gave it to you. So we can’t control that,” said John Womack, the systems operations manager at the Colorado River Municipal Water District. “Especially with all the wind we have out here, and all the heats we have in the summertime. This is a very arid climate. That is our biggest enemy: the evaporation.”

But, thanks to toilet to tap, the District now saves 1.7 million gallons of water a day.

Here’s how that wastewater is treated:

Step one is a micro filter. “The beauty of a micro filter is that they have the ability to filter down to one-tenth of a Micron which is a very small particulate,” said Womack.

A micron is a millionth of a meter. This step gets most bacteria, but not viruses.

That’s step two, reverse osmosis. “Water is being diffused by a cellulose membrane so you’re getting down to the atomic level,” said Womack. “Individual molecules of water are going through that membrane and not allowing other molecules to go through.”

Next the water goes through intense UV Processing. They add in a small stream of hydrogen peroxide. Then, that gets shaken up and spread through the water before it enters the UV light chamber.

“Inside each one of those reactors are 72 light tubes. They look like a fluorescent light bulb. So no matter where you are, where ever the water is, it’s getting exposed to this UV light,” said Womack. “And that reacts with the hydrogen peroxide, and it will kill or destroy anything left in the water.”

What comes out is basically pure H2O, no minerals.

Next that water is mixed with some of the regular lake water in the pipes on its way to a city. The whole batch is treated again at the city plant.

But, by the time it gets to Brandi Mayo’s restaurant in Big Spring, it’s no longer mineral-free — and it’s not so great.

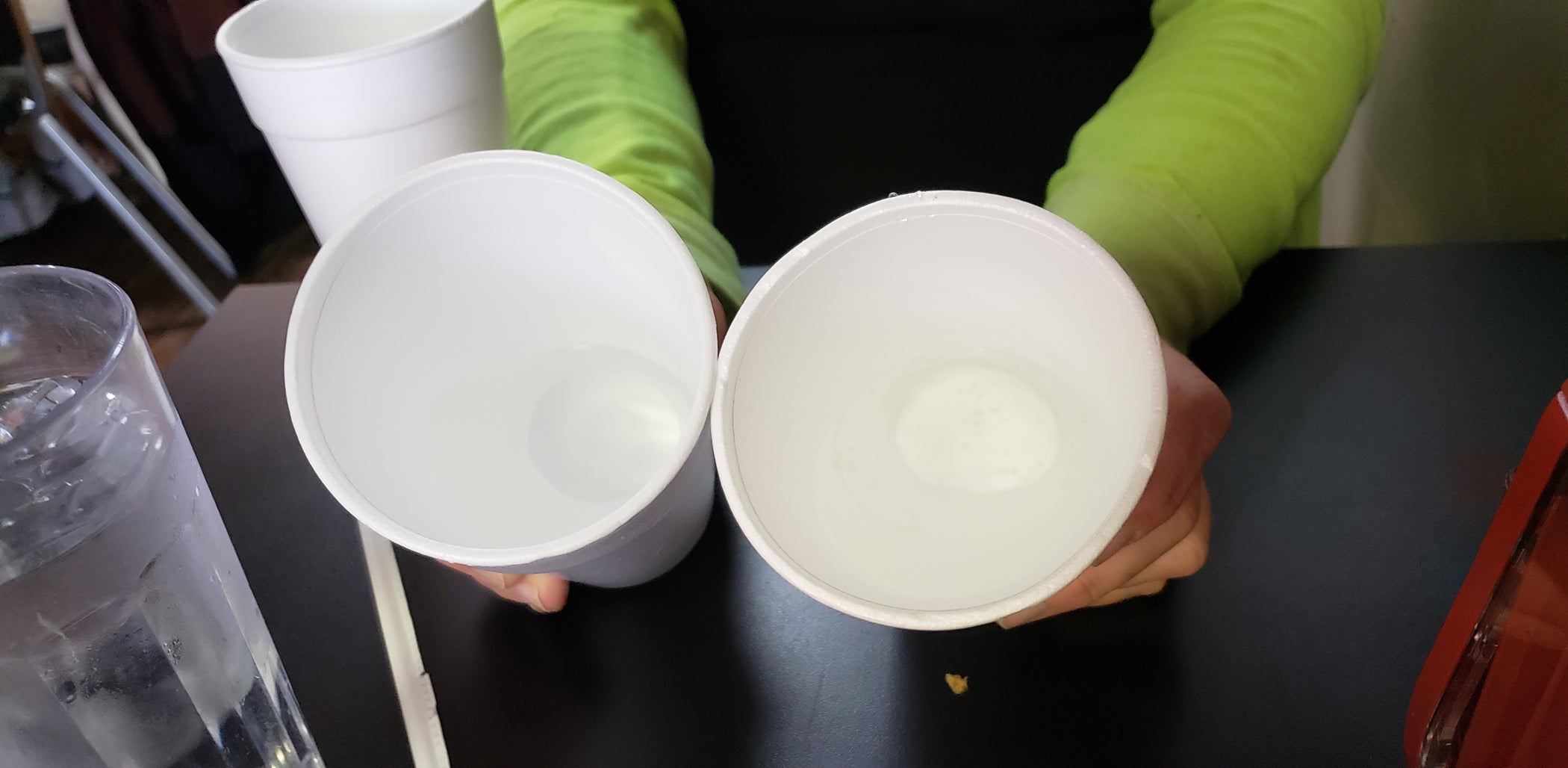

Mayo opened the Mayo Sauce Family Diner two years ago. First on her checklist of restaurant necessities? A reverse osmosis (RO) system. She brings out two glasses to show the difference between the water from the tap and the water from her RO machine.

“Quite the difference actually. One is like nice and crystal clear. The other one kind of has a yellowish tint to it. It taste really awful because it already smells bad,” she says.

And her customers specifically ask about filtered water.

“The first time people order water here they ask, ‘Is it reverse osmosis?”’ she says. “And if, no, surely they would say, ‘Well, I’ll take a Dr.Pepper or something else.”’

In this area, it’s pretty common for a restaurant to have its own reverse osmosis system. That was true even before the whole toilet to tap situation began. The water here has long been yellowish.

But City Manager Todd Darden says, looks aside, the water is fine.

“It’s a quality issue, not a health and safety issue. As far as the state goes, it’s more of a nuisance-type situation,” he said. “A lot of it’s a result of the pipes. You know, most of the pipes in Big Spring are metal, made of iron. That’s the constituent that’s being released from the pipe that’s getting in the water.”

He said an additional reverse osmosis system for the whole city would be overkill.

“That’s just not feasible, and it’s a waste,” he says. “You wouldn’t want to use that on your grass.”

Mayo’s system isn’t cheap — it’s basically step two of the DPR treatment process — but it’s not uncommon for private citizens and business owners to have one in Big Spring.

Dicky Wright is a water purification dealer who has been selling such systems for decades.

“My great-grandma bailed her water and put it in a bucket and brought it in the house. I thought that was cool because I helped her,” Wright said.

He says crystal clear water is just a luxury, and he remembers a time when people didn’t really care one way or the other if their water had a color to it.

“People didn’t care what they got. It was water. Over a period of time they went to these bottled water. You see everyone caring a little bottled water around,” he said. “It’s like all the cars now. All the cars now have air conditioners. When I was a kid, they didn’t have air conditioning. [In] 1956, I rode in a car that had air conditioning, scared me to death.”

The water is tested daily by the city. It’s safe to drink, but people just don’t trust it. That keeps Wright in business.

“People are just more conscientious about it, and that’s it, you know, and they go, ‘Well my kids not drinking city water cause I don’t want them to have it,’” Wright said. “Well, it wouldn’t hurt them a bit to drink Big Spring water. It will not kill them.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.