For some people who stutter, fluent speech is overrated

While researchers are working toward a "cure," some stutters consider that prospect “a little bit eugenic” and say it’s time to embrace neurodiversity.

Listen 10:41

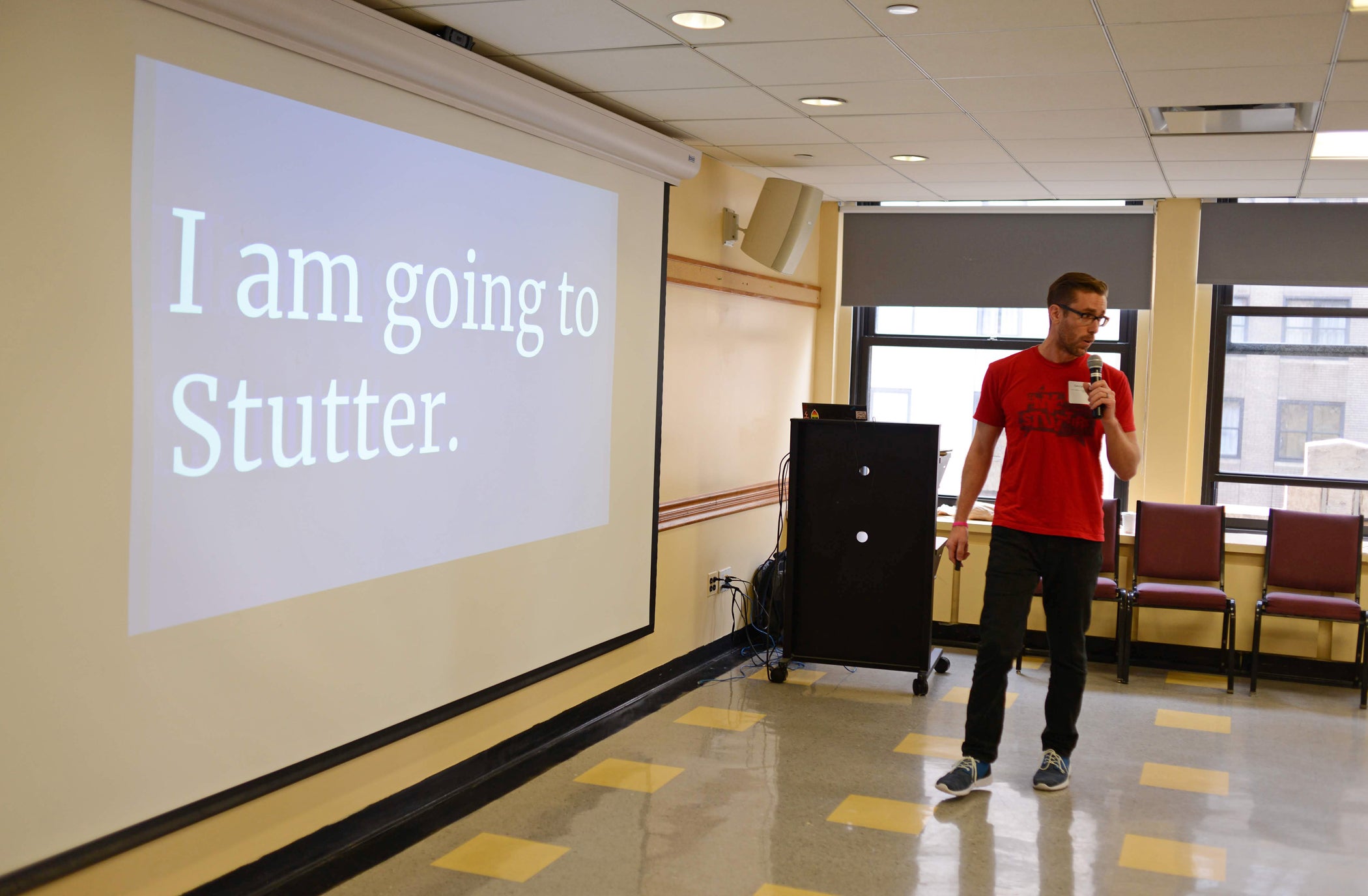

During an icebreaker at the 2018 NYC Stutters conference, attendees play with movement and sound — a treat for those who grew up hating their voices. (Photo courtesy of Paul Isgard)

When I open my mouth to speak, sometimes the sentences flow with an effortlessness that most people take for granted. Other times my face clenches and the words come out in repetitive machine-gun bursts, or else they dissolve into silence.

Like about 1 percent of the world’s population, I stutter.

The condition is complex, and often likened to an iceberg. Above the surface are the repeated words and the visible struggle. Below lie shame, fear and isolation.

Stuttering often begins in childhood.

“Whenever I blew out a candle on a birthday cake, or made a wish in a fountain, or anything else like that, I always made the same wish, which was to not stutter anymore,” says my friend Emma Alpern, a New York copy editor. “My constant overarching goal in speech therapy, and just in life in general, was to not stutter.”

Compounding the distress for me was the unknowability of stuttering. For much of my life, it was a scientific black hole. That’s changing. Researchers are untangling both the genetics and the brain chemistry of people who stutter. And they’ve made progress in drug development, looking at medications that might alter that chemistry and reduce the stuttering.

Many of my peers who stutter are excited about this. From the time we were children, we were taught that stuttering would hold us back in life, and that the only way forward was not to stutter.

In the small, organized stuttering community, there’s a persistent hope for a breakthrough that will lead to a cure. Some people are even raising money to help fund research.

But others who stutter, including myself, believe we should rethink the assumption that stuttering is a defect that needs to be eradicated.

I wanted to talk with people who shared this perspective. On a Sunday morning, I went to a conference in New York sponsored by the group NYC Stutters. It was a day-long brainstorm about how stutterers can support one another better.

Looking at the crowd, the 75 or so attendees seemed to have virtually nothing in common, except for stuttering. Some said they longed for the cure: their lives have been hard, and they wanted their stutter to go away.

Others shared a different vision.

Chris Constantino, an assistant professor in communication sciences and disorders at Florida State University, was a speaker. Constantino, who stutters, is the author of a 2018 article, published in the journal Seminars in Speech and Language, suggesting that people who stutter should embrace an idea called “neurodiversity.”

The theory is that humans have natural variations in how our brains work, and that we should honor many of those differences rather than labeling them pathologies, or problems. The term “neurodiversity” originated in the autism community, according to Constantino. Many groups have championed similar ideas.

For example, some deaf people have rejected cochlear implants, which make it possible for them to interpret sound. They say that deafness is a culture worth preserving. And gay and lesbian activists led the charge against therapies aimed at turning people straight.

For those who stutter, neurodiversity doesn’t just mean tolerating our speech patterns. Rather, it means viewing stuttering as an advantage — for example, as something that can bring people closer by encouraging honest conversations.

“How I like to see stuttering is — it’s as if we’re temporarily stripped of our clothing,” Constantino says.

“We’re temporarily naked. And we don’t have control over when we’re forced to be vulnerable. However, the more time you spend defenseless with others, the more chances you have to connect deeply with somebody, because they’ve seen you. And they’ve seen all of you. And all they need to do is reciprocate. All they do need to do is strip down too. And by stuttering, we give them that opportunity.”

Alpern, who spent much of her childhood wishing for a cure, helped organize the New York conference. She says events like this have helped shift her priorities.

“I really don’t want to begrudge any stutterer for wanting to not stutter,” she says. “It’s very difficult. I get it. To me, it feels a little bit eugenic. I don’t like the idea of us being wiped out. I’ve found an incredible community, and stuttering has brought a lot of meaning to my life.

“Maybe what I really want to say is that I want us to be having deeper conversations about stuttering,” she says. “I think it’s hard to have them when we are simultaneously putting our resources toward a cure.”

Alpern’s point resonates with me. The National Stuttering Association, the country’s leading organization for people who stutter, has the word “cure” in its vision statement. For me, that focus makes it harder to talk about the positive value of stuttering.

The conflict can hit on a personal level, too. Trying not to stutter can feel like full-time work. During the 20 years I went to speech therapy, there were homework assignments that took me hours each week. I called telephone operators and hotel reservation lines, practicing the techniques I’d learned, and hoping not to stumble.

But in a 24-hour day, we can only devote so much energy to thinking about how we talk. When I quit seeking fluency, it freed me up to shift that energy elsewhere.

Some of my friends have had similar experiences. George Daquila works as engineer at the investment bank Goldman Sachs. He’s a snazzy guy who sports a stylish haircut and glasses, and his smile is intense. So is his stutter, but he doesn’t shrink away from it. He says this was not always the case.

“As a child, probably up till I was 28, I would have just wanted to get rid of it as quickly as I could,” he says.

It took both a speech therapist and a counselor to convince Daquila to rethink his fluency quest. By the time he joined Goldman Sachs in 2015, at the age of 31, he was starting to think of his stutter as an asset — a challenge that toughened him for the competitive world of Wall Street.

“Goldman is a very intense culture of some really smart and really driven people,” Daquila says. “What I only understood once I came here was that my stuttering journey was so damn tough, that it really gave me that gift of that really unrelenting drive.”

One of Daquila’s goals has been to connect with others who have disabilities, and to build a more disability-friendly workplace. One of his allies is Vanessa Kelly Smith, an attorney at Goldman Sachs who identifies as deaf. The duo first met over coffee in 2017.

“Our stories were very, very similar in that we had spent a significant portion of our adult life not really comfortable with our disability or fully inhabiting it,” Kelly Smith says.

“I saw George as just someone who was just incredibly comfortable in his skin. We had very similar visions of what we want to do with our advocacy, which is to reframe how disability is seen, and to talk more about the strengths that come from having a disability.”

Daquila wants to help others navigate the corporate job market. He’s organized mock job-interview days for people who stutter. (It’s an idea that has since been adopted by another employer, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation.)

Before they conducted the interviews, Daquila’s colleagues went through a training. They learned the science of stuttering, how people manage it, and how to listen respectfully.

Afterward, Goldman Sachs employees gave feedback to the interviewees — not about how fluently they talked, but rather about their interviewing skills.

“The point of the day was interviews, but it was really more like tearing down the wall that I used to have,” Daquila says. “I was absolutely scared that, inside the walls of a company, there wouldn’t be any acceptance of my stuttering, which was not true.”

Daquila says he was afraid that people wouldn’t take the time to listen to him. He was wrong: they were patient, and they valued him. A few months after his hire, Daquila was promoted to vice president.

Leaving his office, I thought about what stuttering has given me. Like Daquila, I have that “unrelenting drive” — the resolve to prove myself by succeeding professionally. My conversations are more intimate because of my stutter, and I have a community that embodies that drive and that intimacy.

With all those gains, it’s hard these days to think of my stutter as a defect.

If you stutter and want to connect with others, contact a local chapter of the National Stuttering Association. If you have a child or adolescent who stutters and needs support, contact FRIENDS and the Stuttering Association for the Young.

For more resources about stuttering, including information about research, contact the The Stuttering Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.