Fearing drug traffickers in Mexico, family takes sanctuary from deportation in N. Philly church

Federal immigration authorities ordered Carmela Apolonio Hernandez to leave the country by Friday, but she has no intention of complying.

-

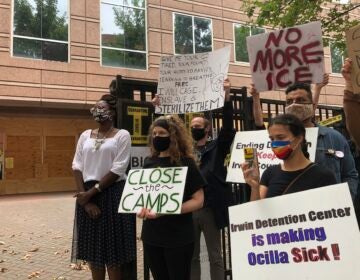

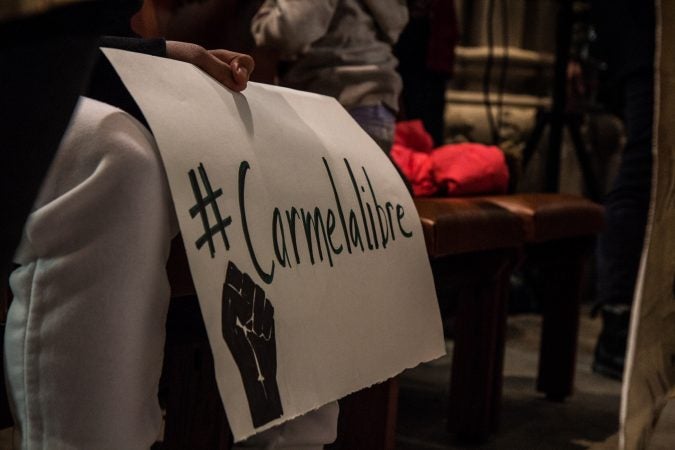

Carmella and her family ask for support on social media. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Carmella and her family listen as Rev. Renee McKenzie addresses the media and congregation.(Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Rev. Renee McKenzie embraces Carmella at the Church of the Advocate in North Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Carmella and her family ask for support on social media. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Rev. Renee McKenzie addresses the media and congregation.(Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Rev. Renee McKenzie addresses the media and congregation.(Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Carmella’s children, Fidel, 15, Keyri, 13, Yoselin, 11, and Edwin, 9, will take sanctuary in the Church of New Advocate with her. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Carmella’s children, Fidel, 15, Keyri, 13, Yoselin, 11, and Edwin, 9, will take sancuatary in the Church of New Advocate with her. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Carmella shares her story of life filled with violence in Mexico. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

-

Church of the Advocade at Diamond and 18th Streets in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This week, 36-year-old Carmela Apolonio Hernandez and her four children moved from their home in Vineland, New Jersey, to a small room in the basement of George W. South Church of the Advocate in North Philadelphia.

Federal immigration authorities ordered her to leave the country by Friday, said Hernandez, but she has no intention of complying.

“I lost three loved ones in Mexico because of the drug wars. Two were my nephews, and one was my brother,” she said. “I was getting extorted and facing death threats, so I cannot go back.”

Her children Fidel,15, Keyri, 13, Yoselin, 11, and Edwin, 9, stood near her as Hernandez talked about her situation to about 50 supporters gathered in the church.

The family is from Guerrero, a state in Mexico southwest of Mexico City, where drug-trafficking organizations have a stranglehold on vulnerable communities. Earlier this year, headlines from The Washington Post proclaimed Acapulco, a major city in Guerrero, the “murder capital of Mexico.”

Hernandez and her family left in 2015, applying for asylum upon reaching the San Diego Port of Entry. They lost their case — and subsequent appeals to the Bureau of Immigration Appeals. Their case is now before the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“The immigration judge in Philadelphia denied her claim, I believe wrongly,” said immigration attorney David Bennion, who represents the family. “The entire system is very hostile to asylum claims, even where there is a clear acknowledgement of danger.”

In the meantime, immigration officers instructed Hernandez to buy nonstop tickets to Mexico for herself and her family.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has had a longstanding policy of avoiding arrests in sensitive spaces, counting churches among them. A spokesman for the agency confirmed that policy is still in effect. That has led some immigrants facing deportation to take “sanctuary” from deportation in places of worship. Earlier this year, Javier Flores Garcia walked out of Arch Street United Methodist Church in Philadelphia, after nearly 11 months of living there to avoid his own removal order.

A kind of voluntary house-arrest, taking sanctuary is seen by many as a drastic last resort. But Hernandez showed no hesitation, and spent eight days looking for a church that would house her family, first in New Jersey and later in Pennsylvania.

“I made the decision because of my children,” she said.

The New Sanctuary Movement, a Philadelphia-based advocacy group, connected the family to the Church of the Advocate. Their basement room has no windows, and three mattresses pushed together on the floor. A whiteboard on one wall and posters of Spiderman betray its former use as a classroom.

“He is protecting me,” joked Hernandez.

—

This article has been updated to reflect comment from an ICE spokesperson.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.