Documentary explores the UFO sighting that changed the course of 62 children’s lives

In ‘Ariel Phenomenon,” filmmaker Randall Nickerson explores who and what we believe

Listen 13:10

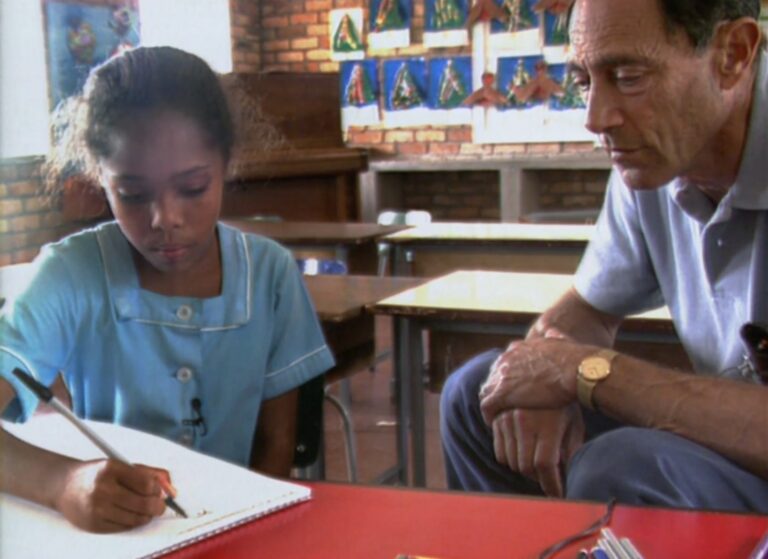

In this still from "Ariel Phenomenon," a student draws a picture of what she witnessed on the day of the UFO encounter while psychiatrist John Mack looks on. (Courtesy of John E. Mack Institute)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

When I asked Randall Nickerson what led him to make “Ariel Phenomenon” — a documentary about a mass UFO sighting by 62 school children in Zimbabwe — he told me the answer was personal.

“I was also very young when I first saw something that didn’t make sense,” he said.

Nickerson doesn’t like talking about exactly what it is that he saw, except to say that it happened more than once while he was out roaming the acres of forests surrounding his childhood home in Massachusetts. He doesn’t consider himself a “believer” — a term that implies faith without proof — so much as a witness.

“I didn’t have to believe it because I saw it — there’s a big difference,” he said. “Nobody’s explained the things that I’ve seen.”

Nickerson describes himself as a nuts-and-bolts kind of guy; a realist. But these experiences never left him, and as he got older, they weighed on his mind.

“It’s very isolating, I think, because you really can’t talk about it,” he said. “And even with other people who have had the same experience, you really don’t talk about it too much because it’s so disturbing.”

The genesis of ‘Ariel Phenomenon’

For years, Nickerson kept his experiences shut away in his mind. He attended a few meetings with other “experiencers,” as they’re called, but mostly, he stayed on the sidelines.

Until he was approached by the family of Harvard psychiatrist John Mack in 2007. Mack had recently died, and his family wanted Nickerson to make a short film about the psychiatrist’s work with UFO experiencers — specifically, about his work at the Ariel School, where the Zimbabwe sighting took place in 1994.

Nickerson agreed, and began poring through hours of video interviews that John Mack had done with the children. Quickly he realized this was a much bigger story than he could fit in a short film.

Over the next 15 years, Nickerson made three trips to Zimbabwe, conducted dozens of interviews, and, along with his team, immersed himself in hours of archival footage — all in an effort to piece together one of the strangest and most haunting UFO sightings ever recorded.

A reporter, a psychiatrist, and 62 school children

For John Mack, it all started with a phone call from BBC’s Zimbabwe correspondent Tim Leach.

In September 1994, Leach — a hardened war correspondent, who passed away in 2011 — had been reporting on the Ariel School incident, and didn’t know what to make of it. It was a bizarre and eerie story, and weeks later the kids remained terrified and disturbed.

His quotes, along with those of John Mack and the school children, are drawn from archival tape included in “Ariel Phenomenon.”

“I could handle war zones, but I could not handle this UFO thing,” Leach said. “It just didn’t make sense. And that’s when I had to call in extra help.”

By that time, John Mack had earned a growing reputation as an expert in UFO encounters. It was considered an odd, even disreputable, choice for Mack, a Pulitzer Prize winner and head of Harvard’s psychiatry department — but, Leach reasoned, Mack’s experience and credentials would bring a level of credibility to his reporting, and maybe help get to the bottom of what had really happened.

When Mack arrived at the school a few weeks later, trailed by a filmmaker, he asked Ariel’s headmaster, Colin Mackie, what he thought had happened.

“Do you think it’s possible that one imaginative child had a story and kind of stirred the rest of them?” Mack said.

“I don’t believe that, I don’t believe,” Mackie said. “I honestly believe they saw something, but for me to actually draw a conclusion as to what it is, I don’t think I could do that at this point in time.”

The rest of the staff at the Ariel School had mixed opinions.

Subscribe to The Pulse

In the documentary, one teacher said he thought the children made the incident up after hearing news reports of what some speculated were meteorites in the sky.

Two other teachers said they believed the children — one, because of the sudden and universal panic that erupted the day it happened, and the other because of drawings the kids had made of the incident.

“So many of the drawings were similar,” she said. “And also when they wrote their stories in their story books, they definitely seemed genuine, because I mean they all wrote completely different stories but they had seen the same thing. And I think that’s what convinced me because I think I was as skeptical as everybody.”

Reconstructing the encounter: ‘It was running in slow motion’

Through a series of interviews, John Mack pieced together a narrative of what happened.

It was a Friday morning, and Ariel’s teachers were inside holding a staff meeting, while the students — kids ranging in age from 6 to 12 or 13 years old — were outside playing.

One little girl who Mack interviewed, named Haley, said that what caught her attention was a strange sound.

“What was it like?” Mack asked her. “Like a roar or a buzz or a hum? Or what kind of a noise?”

“It was like someone was blowing a flute,” she said.

Other kids reported a buzzing sound, like bees or electricity. Several described seeing a silver object whizzing through the sky, and then landing near some trees. The kids all ran over to see what it was.

“We got closer and closer, and we saw this silver thing just shining,” said a girl named Candace in a news interview. “We thought that it was just a house with glass reflecting in the sun and shining. Then we thought, no, it can’t be that, because there’s no houses up there on the rocks.”

It was at this point that the kids described seeing two figures — small, maybe 4 feet tall, dressed in skin-tight black bodysuits. They had narrow, pale, almost plasticky-looking faces with two enormous black eyes. One of the figures stayed on with the ship, and the other started running through the grass.

In one of John Mack’s interviews, a student described the figure running “bouncy, as if a human would run on the moon.” Several other children said it looked like he was running in slow motion.

They were close to the whole scene, just a few feet away — and yet somehow, they said, it looked like the ship and the figures were glitching.

“It was running in slow motion diagonally down the field,” one of the students named Claire recalled many years later as an adult. “And then suddenly, it would reappear in the corner where it started and do the same thing. And then it would reappear and do the same thing. And that was frightening — more frightening than seeing what these things actually were.”

Finally, the figured stopped in front of them. In their interviews with Mack, the children, over and over again, focused on its eyes — big, black, shiny pools that they found they couldn’t look away from.

“It looked evil because it was just staring at me,” one girl said. “As if it wanted to come and take us.”

The message: ‘People would be dying’

The figure never actually said anything, but several of the kids who were looking in its eyes said that they somehow received a message in their minds.

A few of the children said it was “about something that’s going to happen.”

When Mack asked what that something was, the kids returned different answers, but all along the same theme.

“Pollution,” one boy said.

“I think they want people to know that we’re actually making harm on this world,” said a girl with blond pigtails, “and we mustn’t get too technologed.”

Most chilling was the vision of a third little girl.

“It was like in the world, all the trees would just go down and there would be no air and people would be dying,” she said. “I think that in space there’s no love and down here there is.”

What happens when you’re not believed: ‘You think that you’re mad’

After interviewing all the children and several of their teachers, Mack gave a talk to the parents — and he told them he believed them.

“The children we talked with clearly were talking about a phenomenon that occurred in physical reality,” he said. “The stories were consistent and the way they talked about it left virtually no question in our minds that what happened was just about what they said happened.”

For a while, the story was global news — and then it mostly faded away.

Until Randall Nickerson picked up the thread in 2007.

He ended up interviewing 43 of the former students. Some were excited to talk, while others would only agree to share their memories off-camera.

“And that said a lot too — the hesitancy,” Nickerson said, “the fear of ridicule, fear of not being believed.”

Part of what Nickerson found convincing was that, in his conversations with the now-grown children, none of them recanted their former stories. Though since the film came out, one of the students has claimed in a Netflix documentary series that he invented the entire story, and that his classmates were either lying or recalling false memories. His classmates dispute this.

In fact, Nickerson said, their memories stuck almost exactly to their original stories. What had changed for those who wouldn’t go on camera was their willingness to be open about it.

“I think that’s very common,” he said. “You really don’t want to say something to somebody that you really care about or that’s going to scare them away. You know, whether they believe you or not, right? Whether they believe you, and that scares them away, or they think you’re crazy, that scares them away. I really think that people do try to share it, and they get some negative feedback, and then they learn to be quiet about it.”

You can already see that happening in an interview the children did with Dutch TV presenter Tineke de Nooij not long after the sighting. In the clip, de Nooij asks them what happened when they went home and told their parents.

“Some of them didn’t believe us,” one child answers.

Others said that one parent or family member believed them, but the other didn’t.

“Is that hard?” de Nooij asks. “Because if you see something and nobody believes you, what happens?”

The children return a volley of answers:

“People say to you, ‘No it wasn’t true,’ so you think it wasn’t true.”

“And you think that you’re mad.”

“And after that you get all upset.”

“Yeah, and everyone starts teasing you.”

“And my friends over the road, when I go there and I tell them about it, they just say, ‘Oh, he believes in aliens, he’s stupid.’”

Nickerson says whether or not the kids were believed — or even listened to — seemed to have a big impact on whether or not they were traumatized by the memory. Some of the local kids, for example, who grew up in cultures that believed in spirits seemed to fare better. Others did worse — like a woman in the documentary named Emily Trim, whose missionary father forbade his kids from talking about the experience, and soon after returned his family to Canada. Even today, Trim says in the film, she struggles in her relationships and with the memories.

The blackballing of John Mack

Things were also very difficult for John Mack. In the years after the Ariel School incident, he did interviews and wrote books and articles about people who had claimed to have encountered — or in some cases, been abducted by — UFOs. He was a Pulitzer Prize winner and a tenured Harvard professor — but according to his son, Danny Mack, none of that protected him from the fallout.

“There was an inquiry at Harvard and people were challenging his methods, challenging the credibility of what he was reporting,” he said. “And then at some point it became this challenge to his tenure and his professorship.”

Danny says his dad had always been something of a maverick in the field of psychiatry. But UFOs and alien abductions were a bridge too far for Harvard, and even a lot of Mack’s friends.

“That was probably the most painful thing,” he said. “His close friends, colleagues — his sister and my mother, for that matter — were telling him he’d gone off the deep end. People who totally hung with him as he evolved his career into new areas, just couldn’t go there with him. And so that was very painful for him — to not be believed.”

Even Danny was skeptical at first, though he says he ultimately believed his father.

“I think because it was him and, in general, his word was very trustworthy to me,” he said. “Just the nature of who he was — besides that he was my father — he was a scientist first, and an objective thinker first. He just was open-minded and inquisitive in a somewhat unique way.”

In the end, Harvard cleared Mack of any wrongdoing, and in the final years of his life he continued researching and writing about UFOs, until his death in 2004 after being struck by a drunk driver..

But filmmaker Randall Nickerson says the psychiatrist never got over his feelings of betrayal — feelings that are familiar to most if not all people who say they’ve encountered UFOs.

So what is it that makes not being believed so painful for experiencers?

“I think part of the pain is that when you see something so foreign that is more intelligent than you, the thing you want to do most is run to your own people and hug them,” Nickerson said. “And you can’t do that. I think that’s the hard part. It can be extremely traumatic, particularly if you’re alone.”

The kids from the Ariel School, adults now, are less alone now — thanks to Nickerson’s documentary, and things like the U.S. Congressional UFO hearing. Some of them are happy the idea of UFOs is becoming more mainstream; others, Nickerson says, are disturbed.

“They also try to not think about it in any way possible,” he said. “Because of the implications it brings up, and then the big world questions that it also brings up, which is, who — what were those things? How could they do the things they did? What does that mean for humanity? The questions that come up are astronomically huge. But the thing I’m excited about is we’re addressing it, you know, at least it appears we are. And that to me is exciting.”

Learn more about John Mack’s research through the John Mack Institute.

Streaming versions of “Ariel Phenomenon” are available on Amazon Prime, Apple TV, YouTube, and Google Play. Visit the documentary’s website to learn more. The next live screening is on November 16, at the Sun Valley Museum of Art in Ketchum, ID

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.