Color and convenience wooed Americans, and we fell in love with plastic

Sensory treats were possible, things like bright kitchenware and fun toys. We got hooked.

Listen 8:16

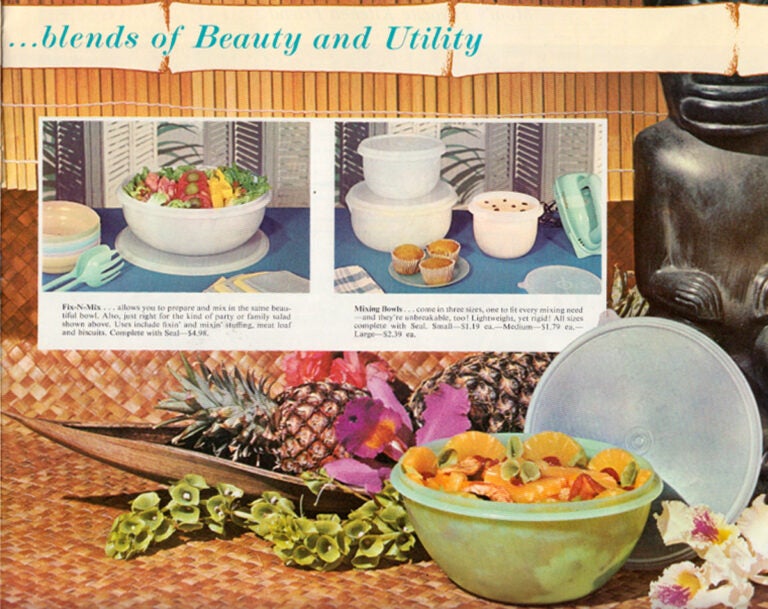

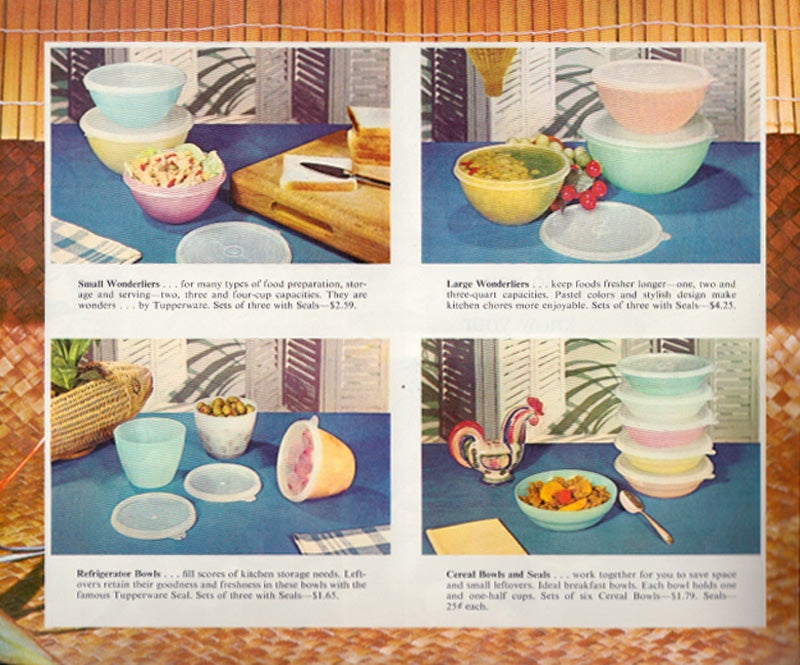

A tiki-style Tupperware magazine ad from the 1960s. Tupperware was created by Earl Tupper, a chemical engineer with Dupont, and began to enter the home after World War II. (Courtesy of Sarah Archer)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Housewares made of plastic began entering the domestic sphere in a big way after World War II. At first, American housewives had to be sold on the idea of using this strange stuff their mothers never had.

They saw it advertised in magazines, but they needed to see it, and touch it for themselves. They needed to smell it.

“Plastic, as all of us know when we open a new shower curtain liner or get into a new car, has a smell, and in the ’40s it was totally alien,” said Sarah Archer, author of “The Midcentury Kitchen.”

“Nobody knew what this was.”

And so the Tupperware Party came to be. Research chemist Earl Tupper had invented a malleable plastic tub that famously “burped” when it sealed. He needed a way to sell this material, derived from a waste byproduct in oil refineries, to women as a food safe container. So Tupper turned to a marketer in Florida, Brownie Wise, who had conceived an idea to bring products into residential homes and have housewives sell it to one another.

“A Tupperware party was a place to see the products demoed, see all the fashion colors that were available — the pinks and turquoises — and see that it was, air quotes ‘safe,’” Archer said. “We now know plastic is not without risk or consequence, but at the time it was a way to get used to the material and have it become part of life.”

Plastic — or, more accurately, synthetic polymers — emerged in retail markets as Bakelite in the early 20th century. But it exploded on the retail market after World War II: Formica countertops, vinyl floors, candy-colored dishware and cups, etc.

“For years and years, kitchens were wood and cast iron in the 19th century, and in the teens and ‘20s, sterile like a doctor’s office with white enamel on black metal,” Archer said. “The idea of introducing a fashion color — like pink or turquoise — was thrilling.”

Plastic helped change the way people used their homes. Midcentury families were starting to use their kitchens as gathering and entertaining spaces. A clean, modern, and colorful kitchen that could be presented to guests altered the landscape of the middle-class home.

Though it was aggressively marketed to women in the home, plastic also sold itself: With seemingly endless options of color, style, and function, the age of plastic promised to be efficient, durable, and fun.

People even wrote love songs to plastic. A hit for Cole Porter in 1934, “You’re the Top” from the Broadway musical “Anything Goes,” compares the object of affection to a list of really wonderful things: the Tower of Pisa and the Mona Lisa. Mahatma Gandhi and Napoleon Brandy.

You’re the purple light of a summer night in Spain.

You’re the National Gallery, you’re Garbo’s salary.

You’re cellophane.

More than 30 years later, the band Jefferson Airplane — then at the heart of the American counterculture in 1967 — released the album “Surrealistic Pillow,” which included a paean to a beloved stereo system, “Plastic Fantastic Lover.”

People literally rioted for plastic — specifically, nylon. DuPont had introduced nylon stockings in the 1930s, but during World War II stopped making them in favor of nylon parachutes for the war effort. As soon as the war ended in 1945, DuPont immediately resumed production of nylon stockings. By then, the pent-up demand was far more than the company could supply. In Pittsburgh, 40,000 women showed up to buy 13,000 nylons in stock. Fights broke out in department stores across the country.

Subscribe to The Pulse

An early salesman: Mr. Potato Head

America’s love for plastic was also seeded through toys. Consider Hasbro, a toy company founded in 1923, in Providence, Rhode Island, by the Hassenfeld brothers. They first entered the market with things like a Junior Air Raid Warden Kit, leveraging the impact of World War II, and toy doctor kits.

The brothers found their first big hit in 1952 with a substantially more goofy toy: Mr. Potato Head.

The original Mr. Potato Head was literally a potato: The kit was a set of plastic parts that children would stick into an actual tuber. It was the first toy to be advertised on television, with the commercial showing kids using turnips and carrots to make silly faces.

“They soon realized the potato part was not so smart. The potato would roll under a couch and rot,” said Wayne Miller, a reporter with the Providence Journal and the author of two books about Hasbro. “They went to all plastic.”

Hasbro later felt the downside of plastic. In 1963, it introduced a polymer blob that kids could squish between their fingers. They called it Flubber, a tie-in to “The Absent-Minded Professor,” a popular Disney movie at the time starring Fred MacMurray as the title character who invents a fantastically bouncy substance.

“Kids started playing with it, and started breaking out in all-body rashes,” Miller said. “There was something in that material that caused a toxic reaction. They recalled it, and it nearly sank the company. It was such a horrible mistake they had made.”

Hasbro yanked Flubber off the shelves, but had a hard time getting rid of it. No municipality would allow it to bury or burn tons of toxic plastic. Hasbro attempted to sink it in a lake, but Flubber floats. Hasbro hired boats to skim the lake surface of the stubborn stuff.

Ultimately, Hasbro dug a deep hole on its own property in Rhode Island, dumped in tons of the Flubber, and paved it over as a parking lot.

Hasbro no longer fabricates plastic toys in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, just outside of Providence, but it still prototypes toys there and continues to be a big economic engine in that region.

An arty side

The Hasbro factory influenced artist Jonathan Santoro, who grew up near the plant in the suburbs of Providence, when they were still churning out plastic toys in the 1980s. Santoro is now based in Philadelphia and makes installation art. He creates objects out of plastic, and installs them as a tableau that tells a story, usually some kind of abstract narrative with political and social satire.

“Plastic is something that represents contemporary society. Material can dictate meaning,” Santoro said. “I think about this kind of staged toy sets. This kind of play I feel like I learned as a child.”

Santoro has mixed feelings about plastic: On the one hand, it’s a byproduct of mass consumerism; on the other hand, plastic makes his pieces so alluring.

“I’m trying to negotiate my feelings where something so mass-produced can elicit personal joy,” he said. “They take you in with the sheen, or the color. There’s kind of a siren’s call to it. My work often gets damaged because people — they want to touch it.”

His work speaks to our love-hate relationship with plastic. These days, many people have an aversion to plastic — there’s a long list of reasons plastic consumer products might be problematic — but there are still the alluring qualities of design options, color, form, and function that we have come to associate with quality of life, convenience, and newness.

Think about the feeling of sitting in a brand new car, and the smell of it. There are air fresheners you can buy with that smell, to bring you back to that feeling of being in something fresh and new.

What is it we’re smelling?

“It’s the plasticizer, or the softener in the plastic,” said Ron Kander, a polymer engineer and dean of the Kanbar College of Design, Engineering and Commerce at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

“Your dashboard is made from vinyl. It’s brittle. The reason your dashboard feels like leather, there are molecules put into the plastic to soften it,” Kander said. “That new car smell is the plasticizer evaporating out of the plastic.”

Americans were taught to like the smell of plastic at the first Tupperware party in 1949. But, like the perfume of a rose, it fades.

“Your car gets to be 10 or 15 years old, you stop at a red light, then you go to hit the gas to pull out and your car dies because it’s 10 or 15 years old,” said Kander. “You smack to the dashboard and say, “Dammit!” The dashboard cracks, because now all the plasticizers have evaporated out and it’s brittle again.”

If Americans seem to be turning their back on plastic — see plastic shopping bag bans, a backlash against vinyl siding, and myriad other ways — Kander is hopeful our relationship with it will bloom once again with polymers derived from organic material.

He said bioplastics can be designed with built-in timelines, to degrade at the end of the product’s expected life cycle, making disposable plastics less environmentally harmful.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.