Bodysnatching and the curious case of One-Eyed Joe

Listen 24:18

This piece is part of our “Bodies” show. Take a look at the rest of our stories here.

Dead bodies serve as teachers in medicine and science. They reveal knowledge and insights for each generation of researchers and physicians. Ceremonies honoring the people behind those cadavers, who made the ultimate gift to their medical education and the advancement of science, is a common ritual inside medical schools these days.

Dead bodies serve as teachers in medicine and science. They reveal knowledge and insights for each generation of researchers and physicians. Ceremonies honoring the people behind those cadavers, who made the ultimate gift to their medical education and the advancement of science, is a common ritual inside medical schools these days.

.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }

But at the dawn of modern American medicine, during a time when the profession was trying to establish itself, obtaining these needed corpses wasn’t easy. The need fueled an underground, mysterious practice that would ultimately transform Pennsylvania and the medical community as we know it today.

Caught in the crossfire at the turn of the century was John Frankford, a notorious horse thief from Lancaster, Pennsylvania who made a name for himself for being “an adept” at jailbreaking.

In the winter of 1896, his brain went missing.

Now, more than a century later, an independent researcher with a special knack for locating body parts is trying to find it.

This story was done in collaboration with the podcast Criminal.

‘Laughed at iron cells’

John Frankford wasn’t just any criminal. He was a famous horse thief. Throughout the mid-to-late 1800s, Frankford crossed the region from Ohio to Maryland, skirting sheriffs, stealing and selling horses.

Frankford grew up in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and he once joked to a prison warden that he was responsible for every missing horse in eastern Pennsylvania. But his real notoriety came from his skill of jailbreaking.

“Frankford had the reputation of just not taking prison seriously,” said Evi Numen, an exhibitions manager at the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. Numen has taken a personal interest in Frankford’s story.

“There’s actually an article whose headline is, ‘He laughed at iron cells,'” she said.

Between 1860 and 1885, Frankford was indicted at least two dozen times. He’d get caught. He’d escape. He’d steal another horse. He’d get caught again.

“It’s almost like a running joke,” said Numen, adding that the public didn’t seem too afraid of him.

He was said to have the sympathy of many.

“I imagine him [as] kind of a horse whisperer,” she said.

Frankford mostly ran on his own, with the occasional help of a son-in-law, but had affiliations with the region’s biggest criminal gang: the Buzzard Brothers. It was a group of six brothers. Abe and Ike Buzzard once got Frankford and several others out of jail using their classic ‘jailbird’ trick.

Eventually, the Lancaster county jail became so tired of Frankford’s escapes that they built a special cell for him. But in 1881, he cut through it, then dug under a wall and crawled out the stone chimney. The keeper spotted him and shot him in the face. Frankford survived, but he lost an eye. And so he gained the nickname “One-Eyed Joe.”

In 1885, Frankford finally ‘met his match’ when was caught at a horse sale in Philadelphia and sent to Eastern State Penitentiary, the state’s most severe and famous prison. He was to serve out the rest of a 19 year sentence for horse theft there.

But he never did make it out. At least, not alive. Because inside the prison’s towering, 30-foot walls, it wasn’t just the guards that had a hold on him. The doctor did, too.

This is a story, not about what Frankford did as a famous criminal or inmate, but rather, the mystery of what happened to him – and his body – after he died.

It was part of a broader practice that prison officials appeared to turn a blind eye to, that would ultimately transform not only Philadelphia, but the entire medical community as we know it today.

Life inside the world’s first ‘true’ penitentiary

Eastern State Penitentiary was Pennsylvania’s world famous prison, considered by many to be the first true penitentiary. It’s basically where solitary confinement originated in the United States.

“That’s where the word penitentiary comes from,” said Numen. “The idea of solitary confinement is to perform penance, to kind of reflect on your crimes and try to appease God or get closer to God and really ask for forgiveness.”

Between Eastern State’s opening in 1829 through its closing in 1971, 80,000 people spent prison time there. Only a few dozen ever managed to break out.

During the late 1800s, prisoners would have spent most of their time in their cells. Guards would put hoods over their heads when taking them out to work or exercise. That way, inmates couldn’t see where they were or be recognized by the outside.

Frankford, it was said, was never one to complain, but when his daughter Maggie Rittenhouse once visited him and managed to sneak in a question when guards weren’t looking about what life was like there, he whispered, “Maggie, life is not your own here.”

By the 1890s, about a decade into his term, Frankford wasn’t as closely confined. It was said he had turned into a model prisoner, hoping for a pardon. His work duties included plumbing and plastering. He also looked after the prison’s fierce dogs (he was a skillful horse thief, after all, so one would think he must have had a way with animals).

Around christmas time in 1895, Frankford was tending to the dogs when one of them turned on him.

“And apparently they got in a fight, the dogs did, and he tried to separate them and he got bit,” said Numen.

The bite supposedly got really infected. By mid-January, Frankford took a turn for the worse. He died in the prison on January 20, 1896. He was 58 years old.

Even though he’d been locked away for well over a decade, his obituary was front page news.

The ‘mutilated’ body

Frankford’s daughter, Maggie, traveled with her husband to the prison right away, to arrange for her father’s body to be transported to Lancaster for the funeral. But when they asked to see the body, the prison said they’d have to wait, that it wasn’t ready.

When they finally do see Frankford’s body, it’s a disturbing sight.

“He has bruises all over his body, he has sewn marks and his skull is cut open,” said Numen.

The top of Frankford’s skull appeared to have been opened and then sloppily stitched back together with some sort of twine. His stomach was cut open, too, and the intestines were spilling out.

Frankford had been under the care of the prison’s doctor, John Bacon. Bacon was probably as good a doctor as there was at that time. He had trained under the best of the best at the University of Pennsylvania (he’s even depicted in a famous Thomas Eakins painting on display at the Philadelphia Museum of Art).

Dr. Bacon declared Frankford’s official cause of death as a strangulated hernia, which is an intestinal blockage. Frankford had been suffering from that for a while, and he did have that bad dog bite. But neither of those things explained why his body had been cut up like that.

Another inmate named Alexander Leidsley (though some reports say Leipsner) claimed to have answers. Leidsley was in for second degree murder. Like Frankford, he was from Lancaster. After being released from prison, he contacted Maggie and told her what he’d seen.

On the morning of January 21, 1896, Leidsley had been out of his cell, working on a construction project, and decided to sneak over to the hospital wing to visit his sick friend.

“He seems to think very highly of Frankford, apparently he was well liked,” said Numen.

Frankford had been staying in the hospital wing, cell block three, supposedly falling in and out of consciousness. It was cold and snowing. Leidsley looks around and then, across the yard, he sees Frankford, lying on a table, naked.

“And the doctor, the prison physician, is working on him. That’s how he describes it,” said Numen.

Frankford is dead. Leidsley inches closer.

“He tries not to be seen. He doesn’t want to be discovered,” said Numen. “And he sees Dr. Bacon remove Frankford’s heart, and he puts that on the snow, presumably to keep it fresh. And then he’s working on his skull, and he opens up the skull and takes out the brain and he sets that on the snow, too.

This is the story according to a deposition Liedsley later gave to authorities. Numen’s coworker found the document by chance at a flea market in 2014, and it really struck Numen. She was drawn to stories inside these prison walls, and the notion of personal autonomy even after death. She spent hours transcribing the faded, antique cursive.

Leidsley said that two other inmates also witnessed what happened, and he told Maggie that he would be willing to testify to what he’d seen.

The trial

It’s unclear what came of inmates bodies after they died, whether families had a real say. The prison didn’t appear to be keeping tabs on any of this, but the overall conditions of Eastern State were already under investigation at that time. There were enough instances of poor health and so called “insanity” that a legislative committee sought testimony from inmates, wardens and even newspaper reporters.

Frankford’s death later came under review in the spring of 1897.

The day they looked into what happened to his body, it got graphic. People described the “mutilated corpse.” Leidsley took the stand.

“He said that ‘Doctor Bacon put the entrails in the bucket and avowed that all convicts who died in the prison had been treated that way.’ That’s a big one – that’s what he claims,” said Numen.

But then, Dr. Bacon himself took the stand. He said he’d performed emergency surgery for Frankford’s hernia right before he died – a last ditch attempt to save him. But when asked about what happened to Frankford after his death?

“Dr. bacon said a prisoner whose first name is Arthur had assisted him and had removed the skull and taken out the brain,” said Numen, while flipping through a newspaper account of the trial. “He said the cut over eye was due to carelessness of the assistant, who began to remove the skull too low down…Why did you take out the brain, Dr. bacon was then asked. ‘Because John Frankford was a typical criminal, and I wanted the brain for scientific purposes.”

The news reports said Dr. Bacon denies taking Bacon’s heart but admits to taking Frankford’s brain for science. And then, it’s reported that he admits to taking the brains from two other bodies.

“When I picture this trial, I kind of picture Dr. Bacon being defensive about it, being like ‘of course we did this,'” said Numen.

A researcher at Eastern State Penitentiary, Annie Anderson, was surprised, and even skeptical, of parts of this story, and more specifically, Leidsley’s complete account. That’s in part because while the prison does have records of some autopsies taking place inside the prison to determine an inmate’s cause of death, the prison doesn’t have any records of doctors taking organs for further study.

But Dr. Bacon wasn’t the only doctor taking people’s body parts during that time. Such activity, according to other medical historians, would have been very under the table, but part of a bigger medical practice that was rampant around that time.

Bodysnatching and stealing body parts for science

This was a strange period in American history. The medical industry was just beginning to establish itself. The ambulance and other surgical techniques were new to the scene. Meanwhile, wounded civil war soldiers were returning from battle in need of care.

It all created a growing demand for doctors.

“So you have all these medical schools sprouting that are attracting new students,” said Numen.

Philadelphia was a hub.

But to become great at healing the body, a doctor or doctor-in-training first had to find one to study, to figure out how it worked. The most ambitious attended extracurricular dissection courses, and even took anatomy a second time.

But there was a problem: the math didn’t add up.

“So in 1882, a few years before Frankford’s death, the state of Pennsylvania has 1493 medical students in need of bodies to dissect. Ideally they would need 746 to make that possible because each student gets half a body. But there are only 406 lawfully available,” said Numen, citing the numbers from the book Body Snatching by Suzanne Shultz. “So they’re short by half.”

And yet, a medical school’s reputation depended on whether it could provide students with ‘abundant anatomical material.’ This was also a time when medicine and even the broader public had an intense fascination with the body. It gave rise to anatomical museums, like the Mutter, that looked for unusual body parts to display for study. Doctors amassed their own private collections.

“So they have to figure out other ways to get bodies, and that’s where body snatchers come in, or as they called it at the time, resurrectionists,” said Numen.

The absence of a legal way to meet the demand for bodies fueled an underground, controversial trade.

“The body snatcher term is mainly with medical grave robbery,” said Michael Sappol, a medical historian and author of A Traffic of Dead Bodies.

During the seventeen and eighteen hundreds, these resurrectionists could make good money digging up corpses and selling them to medical schools. The easiest bodies to snatch were those of the poor and vulnerable, who couldn’t afford a watchman or a secure grave. These were African Americans, immigrants, those who died in asylums, almshouses and prisons.

There was also an urgency to get bodies, since they would decompose fast (that’s why dissection classes typically happened in the winter).

In the early days, even medical students got directly involved in stealing them.

“They’d go in the dead of night, they might bribe a watchman or maybe get a watchman drunk or maybe look for moment when watchman falls asleep,” said Sappol. “And then bring in their wagon and horse, unearth a body and…away.”

This might seem horrific by today’s standards, but Sappol says a few things were different back then. For one, students were a lot younger.

“Many come from distant places, in the city, it’s a culture of camaraderie and bravado,” said Sappol. “You want to curry favor with the professor? Bring them a body, an interesting body. You want to curry favor with your classmates? ‘I got a body.’ They’re impressed with you. You’re a brave strong lad.”

And unlike today, where lots of people really want to donate their bodies to science, there was a huge stigma to being dissected or even autopsied. Sappol says nobody wanted this to happen to them or their loved ones.

“This is also a time in American culture where how you die really matters to people,” said Sappol. “And if you’re a poor person and you’re saving money, the money you might be saving would be dedicated to your death.”

In addition, while dissection was never technically illegal in the U.S., for centuries back, it was often listed as an added punishment to those sentenced to execution.

Students weren’t always respectful with how they treated the bodies once they got them, either. And when the public caught wind that they were steeling them, riots broke out. Labs were burned down. In some instances, only being locked in jail could protect doctors and students from community outrage and even death.

“And there are a few notorious examples of times when it became so lucrative that bodysnatchers murdered people to supply the anatomy department,” Sappol added.

Murdering people and selling them to science? Clearly a crime. But the laws to deal with regulating bodies for dissection were a mess at that time, and not just in Pennsylvania.

“This system of looting and bribery and corruption is unruly and unseemly,” said Sappol. “It attracts attention in newspapers. It’s politically embarrassing.”

Lawmakers tried to look the other way, but the public was terrified and angry. By 1878 the popular press reported at least a dozen body snatching scandals in America, including an incident where the body of President William Henry Harrison’s son is discovered stolen from his grave in Ohio.

Then in 1882, just before that famous horse thief, John Frankford, was captured for the last time in Philadelphia, one the most revered doctors in America is accused of body snatching a few blocks away.

Philadelphia’s big scandal and the rise of the anatomy act

“It’s a pretty amazing story,” said Michael Angelo, the archivist at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Angelo is referring to Dr. William Forbes, head of Jefferson’s anatomy department at the time. And a star anatomist and surgeon, who provided care during the Crimean and Civil Wars. He was also wealthy and well-connected.

“In 1882, Dr. William Forbes, the foremost anatomist in the country, here at Jefferson medical college, had a relationship with some people who supplied cadavers for the students,” Angelo said.

Dr. Forbes had actually tried to be on the right side of the law. He penned the first anatomy legislation in Pennsylvania, the Anatomy Act of 1867, to legally direct unclaimed bodies to medical schools. But the law was weak, and the bodies weren’t coming in.

“The local Philadelphia papers knew that something was fishy so they basically set up a sting,” said Angelo.

It was at a very large African American cemetery in what today is south Philadelphia. The crew camped out at night, armed with guns, ready to catch the crime in action.

“They actually got to the bottom of this because there were bodies being stolen every winter from these cemeteries, and so when they arrested these individuals, they squealed and said Dr. Forbes had requested the bodies,” said Angelo.

Forbes was arrested on charges of conspiring to steal bodies and violate graves. There were protests against him and others involved. Some thought it would be the end of Jefferson Medical College, a main competitor to the prestigious University of Pennsylvania.

Forbes denied any involvement. Think of it as a don’t ask don’t tell when it comes to where the bodies came from for his lab.

“But the damning evidence was there were keys to the dead house or the place where corpses are kept at the college in the possession of those men,” said Angelo. “We have the keys in the archives today. It’s a grizzly reminder of where America was 130 years ago.”

Forbes was never found guilty. He was acquitted and returned to his medical post amid a mix of outrage by some in the community and relief in the medical world. Ironically, Forbes used his Jefferson scandal as leverage to help push through a new and improved law that would actually create the legal mechanisms for schools to get the bodies they needed.

“So as Philadelphia went, so did the rest of the country. The Anatomy Act of 1883 was really important landmark for the entire country,” said Angelo.

Again, state laws regulating bodies for dissection were all over the map back then, if they even existed at all. Massachusetts was an early pioneer. In Pennsylvania, this act compelled institutions across the state – prisons, morgues, hospitals – to give unclaimed bodies to medical schools.

An official Anatomy Board was created to coordinate the distribution of bodies, and it marked a huge step in legitimizing dissection in the state. It basically helped transform a profession seen as a bunch of monsters and ghouls in the public’s eye, into one that was really legitimate and respected.

“If you go to state archives in Harrisburg from around the 1890s and onward, they have records of bodies of prisoners who have been executed or indigent people, once again unfortunately who are unclaimed, where they indicate the person, their age, what they died of and what medical school they were sent to,” said Angelo. “So it became real organized and rational with a board making decisions.

(Eastern State has records of sending at last 90 unclaimed bodies of inmates to the anatomical society, up through the year 1935. But with so many people willing to gift their bodies to science, medical schools in Pennsylvania these days aren’t looking to prisons much anymore.)

The Pennsylvania Anatomy Act turned into Forbes’ crowning accomplishment, and it was pushed through, thanks to a state senator, William James McKnight, who also happened to be a surgeon in northwestern Pennsylvania, who years earlier had been convicted of body snatching.

The curious case of John Frankford

The Anatomy Act didn’t lift the curtain on everything. The rules were still gray in certain areas. Sure, it protected doctors, but what about protecting those at the bottom of the ladder, like prisoners and others prone to being dissected or autopsied?

Doctors still took liberties when no one was looking, and back to the case of that legendary horse thief, John Frankford, whose brain was taken, the anatomy act is referenced during the trial, but in news reports it appears that his case kind of falls through the cracks of it.

“So this is an interesting detail. There is nowhere, no clause in the Anatomy Act in 1867 or in the revision that happens in 1883 that talks about organs. That’s never mentioned,” said Numen. “The end of the reporting of the trial actually reviews the prison as almost not responsible for this and there isn’t really retribution for it.”

Numen wonders, if the Anatomy Act had already passed when John Frankford died, why Dr. Bacon might so casually admit to removing Frankford’s brain and not fear major consequences (it’s hard to confirm how he literally reacted, but this is how Numen imagines the situation based on what details were available in news reports).

“It appears that if you can get away with taking organs you can,” she said. “I think what’s happening is Dr. Bacon says that he took out the organs for scientific purposes, and he says that he didn’t know that it was illegal. Or that he didn’t have to ask to do this because his predecessors did it, too. So we know that this is not terribly unheard of.”

Eastern State does have records of some autopsies being performed, but as it came up in Frankford’s trial, the protocols regarding family permissions were unclear (a later correspondence between the anatomy board and Eastern State’s Warden in 1904 discussed seeking state permission for post-mortem examinations).

But Numen says Frankford wasn’t technically snatched for a regular dissection or post mortem exam. During that time, there might have been a keen interest in his brain for other reasons. Aside from obtaining full bodies for dissection, a lot of doctors were looking to get organs on the side to study. And there were networks of doctors helping each other find them.

These were the days when people still believed in phrenology, and the brain of a clever criminal would have been especially desirable.

“So my guess is that they had their eye on him,” said Numen. “This is a famous horse thief.”

Numen is referring to the old popular study of the brain that gained a lot of interest in the nineteenth century. It’s the idea that physical characteristics of the brain could reveal differences, so criminality could be found in the brain and studied.

Collecting and studying brains was also a thing in general at this time. Many really smart people, like Walt Whitman, even donated their brains in pre-mortem agreements as part of The American Antropometric Society, which was informally called the “Brain Club.” (Correction to an earlier statement, thanks to Evi Numen: Einstein – whose slice of a brain is on display at the Mutter – was not, in fact, a member of this group. His brain was initially stolen.)

Beyond the possibility that Frankford’s brain was taken for study, Numen also wonders if perhaps someone just wanted it on their shelf, like a trophy or souvenir. Frankford was, after all, a high profile and seemingly uncatchable criminal. Think about all those sheriffs he managed to outwit, and all those people he ripped off.

Either way, it wasn’t all that unusual to look at and even admire body parts in jars, kind of like the way people look at art in a museum. And there’s one place in particular where that’s still true today: the Mutter, where Numen works.

Searching for Frankford’s brain

Numen wants to see if Frankford’s brain is still around. She’s looking for it.

“I would really love to find his brain, I hope it’s out there,” she said.

“There is no footnote about where it ended up,” she said. “We don’t know if it was sold by Dr. Bacon. If he kept it, if it was returned to the family, there’s no mention of what actually happens to his organs. So my hope is that Dr. Bacon sold it to one of his colleagues and it ended up in a collection and it’s still somehwere out there in Philadelphia hopefully.”

How would a person know?

“It would probably be marked as a brain of a horse thief,” she said.

And if anyone could find it, it’s probably her: Numen’s nickname at the Mutter is the “wet specimen hound.” She’s really good at finding body parts in jars.

The Mutter has several old brains on display in alcohol or fermaldyhyde, and several more in storage. She is not convinced Frankford’s brain is in there, so she has expanded her search to other places.

“One of the things that fascinates me about this story is the difference between personhood and artifact, the remains of someone becoming an artifact after a certain period of time, or becoming an artifact when they’re dissected and removed from this person’s character and life experiences,” Numen said.

So, why would she want to find his brain?

“I always believe that seeing an open casket funeral or the remains of loved ones brings a sense of closure, and this horse thief from the turn of the century has become a fixture in my life for the last two years. So I want to follow the story to the end and see what became of him.”

Numen recently discovered a funeral notice for John Frankford. It said he was buried in Lancaster Cemetery. Numen looked for Frankford’s grave there but she couldn’t find it.

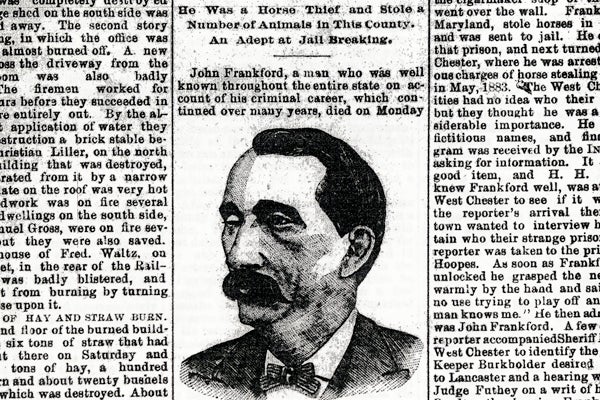

The one thing she does have is an image of him. It’s a sketch from an obituary.

At a quick glance, one might think he appears a little melancholy, like as he once told his daughter, life is not your own inside Eastern State.

But at a closer look, one of his eyelids is slightly drooped over that eye he’s missing because of that bullet that swiped him during an escape.

It sort of looks like maybe…he could be winking.

Like maybe, even in death, this is One-Eyed Joe’s way of managing to sneak away from us all.

His last great escape.

Music featured in this story:

Calexico: ‘Fake Fur’

Tin Hat Trio: ‘Old Wold’

Tin Hat Trio: ‘Comet’

Tin Hat Trio: ‘Bill’

American Catastrophe: ‘The Six Foot Whisper’

American Catastrophe: ‘Tension’

Tin Hat Trio: ‘Dead Season’

Abe’s Retreat

Tin Hat Trio: ‘The Book’

This Way to the Egress: ‘Ballo Di Rago’

Hector Berlioz: Symphony Fantastique

Tin Hat Trio: ‘Esperanto’

16 Horsepower: ‘Heel on the shovel’

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.