Audio Time Capsule: The discovery of Legionnaires’ disease

Solving the mysteries of infectious diseases requires man power, determination, and, in the case of Legionnaires' disease, pride.

Listen 20:51This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

Solving the mysteries of infectious diseases requires man power, determination, and, in the case of Legionnaires’ disease, pride.

From prisons to hotels to hospitals, outbreaks of Legionnaires’ Disease have hit many unsuspecting places in recent years. Last August, New York experienced its worst outbreak in history, with a dozen deaths and many more sick.

Legionnaires’ disease can result in…no, not blistery skin lesions as one might think from hearing the disease’s name…but rather, a potentially fatal pneumonia. Doctors have effective antibiotics to treat it, if the disease is caught early enough. And scientists now know the cause of the disease comes from a tricky bacteria that especially likes to fester in warm water.

Heating and cooling systems, in particular, or HVACs, are prime sources for potential infections. That’s because they produce a mist as a byproduct of the cooling process, and if the legionella bacteria is in high enough concetration, when aerosolized in that mist, it can infect the lungs of someone who inhales it.

A mysterious illness

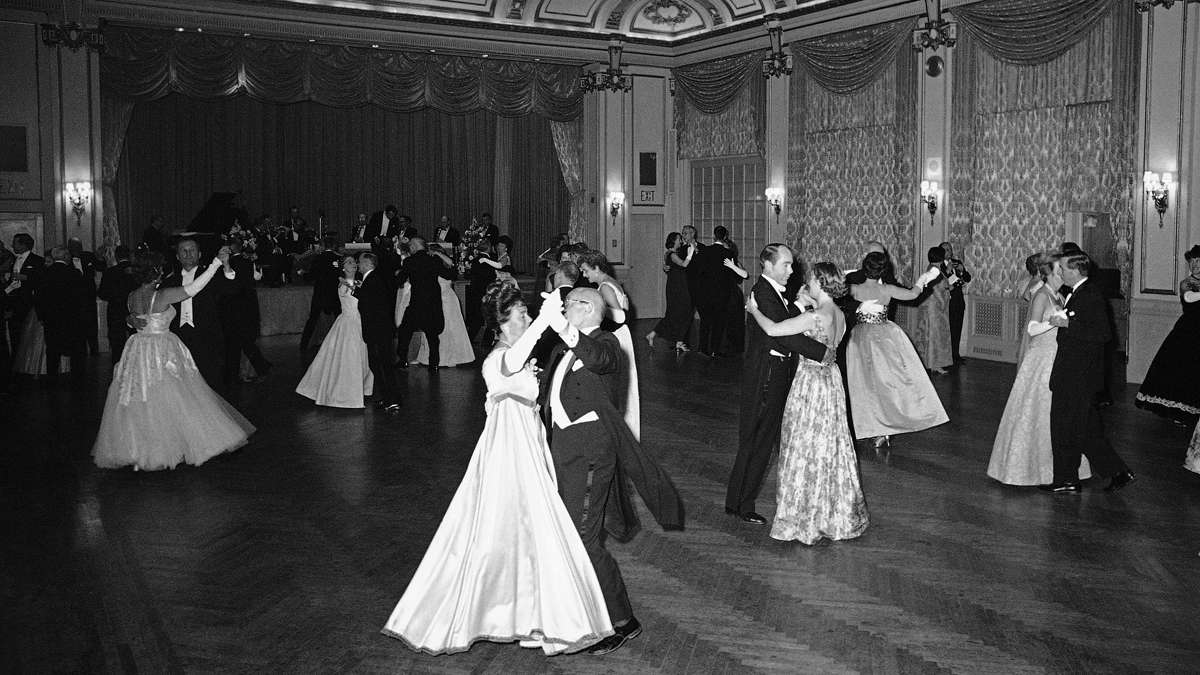

No one knew any of this in 1976, the year the first Rocky film, shot in Philly, hit theaters, and the year the nation held a massive bicentennial celebration in the city. It was a few weeks after this big event that thousands of wartime veterans came in, amid an especially hot summer, for what they thought would be their typical annual conference.

“Well, that was the yearly convention of the department of Pennsylvania,” recalls 90-year-old Jasper Stouffer, a WWII airplane mechanic from south central Pennsylvania and a past department commander of the American Legion. “And then there were a lot of wives and family members there at the same time.”

The Pennsylvania American Legion convention took place from July 21 through July 24, and was packed with committee updates, campaigning by people running for office, and socializing.

But in the days that followed the conference, dozens of American Legion members fell ill throughout the state. Stouffer’s close friend and colleague, Charles Chamberlain, who had just been elected commander of their local post, died six days after the convention from “a flu of an unknown cause.”

“He came home and went to bed, and never got out of bed,” Stouffer said.

90-year-old Jasper Stouffer’s friend died in the 1976 outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

It quickly became clear that Chamberlin wasn’t the only one to succumb to the condition, with other legion members falling ill with unusually high fevers and similar respiratory symptoms—some even ended up in the same hospital as Chamberlin.

Reports of more illnesses and deaths from a pneumonia of an unknown cause made their way back to Legionnaires’ headquarters, then to state health officials and federal disease specialists.

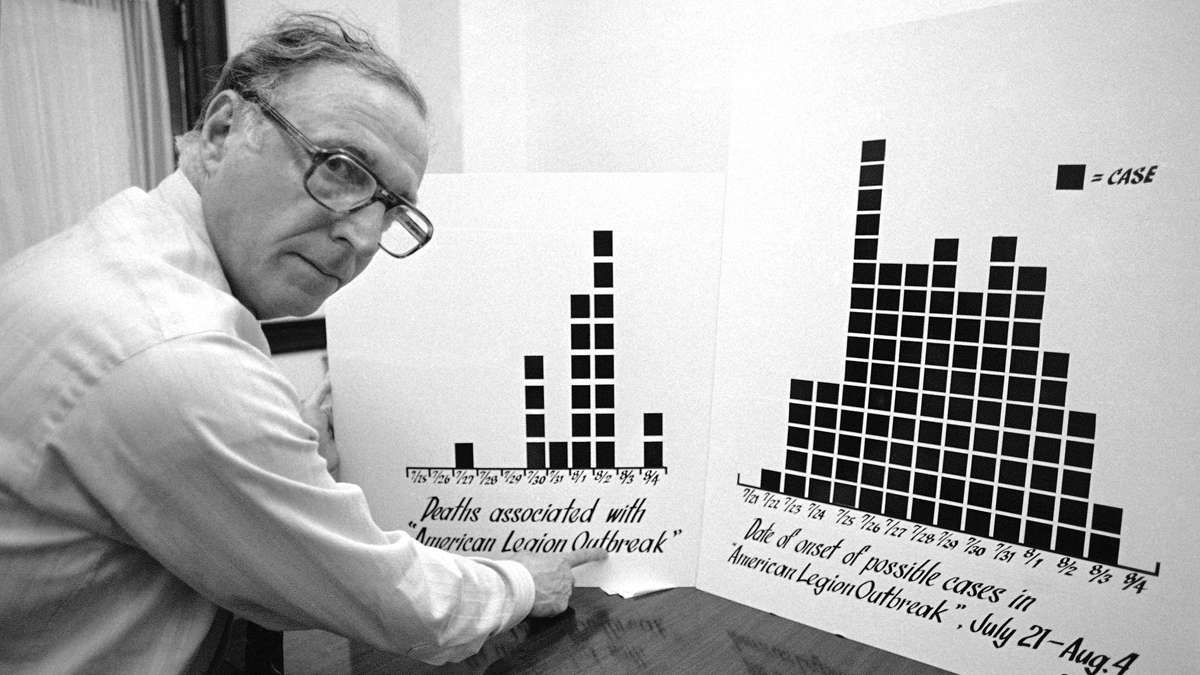

Thirty-four deaths were linked to the mysterious disease outbreak.

The press was all over it.

A massive response

The U.S. had been primed for another swine flu epidemis, with cases spotted on a New Jersey army base earlier that year, and many feared the mysterious illness might turn into a major flu pandemic, like the one that had killed 50 million people in 1918.

Government health agencies mobilized at an unprecedented level.

“This was the biggest investigation the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) undertook at the time,” said Dr. Robert Sharrar, then head of disease control for Philadelphia’s Health Department.

What had caused mostly American Legion members to fall ill? Food poisoning? Contaminated water? A virus? A toxin?

Everyone was stumped, but news reporters quickly dubbed it “Legionnaires’ disease.”

“I spent a very intense plane ride trying to figure out how would I systematically begin to approach what looked to be a very complicated problem,” recalled David Fraser, head of the CDC’s special pathogens lab in Atlanta.

Early on, it became clear the disease was not infectious and spreading. But with high expectations of modern medicine, public and political pressure mounted, and the quest to find answers turned into what many consider to be one of the great medical mysteries of the twentieth century, one that required some serious, shoe-leather detective work to figure out.

As many as 100 state and federal workers were called in. About 50 police detectives took part, with many hand-delivering thousands of questionnaires to American Legion posts throughout the state (no central list existed detailing who had attended the convention and where they had stayed).

“We had to send physician epidemiologists out to take histories from and examine a large number of people,” said Fraser, a native of the Philadelphia area who’d been appointed to lead the field investigation.

They monitored family members of those who’d gotten sick, met with doctors. They telephoned random samples of people who weren’t even at the convention to have a comparison group.

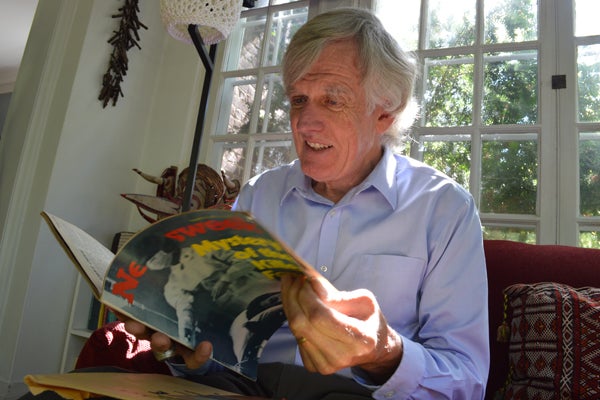

David Fraser reviews old news clippings from the Philadephia outbreak. The Philadelphia area native led the CDC’s federal field investigation. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

A suspect, of sorts

Without solid leads on an actual source of the disease, investigators had one general suspect in mind: the Bellevue Stratford Hotel. This was Philadelphia’s iconic, grand hotel, where many of the delegates stayed and where many of the convention meetings took place.

The focus on the hotel spurred a media frenzy, a publicity nightmare, with people canceling reservations left and right.

“It was just bleak, a real bleak feeling,” recalled Steve Hornstein, a doorman at the Bellevue at the time of the outbreak. “I know for a fact being the doorman, people walk by every day, and you’d greet them, ‘Hi, how are you? Have a great day.’ A lot of people would not walk by the Bellevue when the Legionnaires’ broke out. They’d walk across the street or later, I found out, some people would walk on another street.”

Fraser’s team, meanwhile, pretty confident the disease was no longer a threat, did the exact opposite. They moved in to the hotel for two weeks, combing the place for possible clues, all the while working around the clock with local and state disease specialists, like Dr. Robert Sharrar, to review the evidence and the case notes, also known as “line lists.”

They looked for patterns in how the disease worked and commonalities of those who’d gotten sick, that would hopefully lead to the source.

Two clues emerged: people who spent time in the lobby of the hotel or just outside on the sidewalk were at greater risk for contracting the disease (some people got sick and died who had nothing to do with the convention).

Mounting pressure

How diseases choose their victims is tricky to determine. The Legionnaires were mostly older men who smoked, and it was thought that made some of them more susceptible to getting sick. But without more solid leads at that time, all sorts of theories and conspiracies filled the void.

Maybe the illness came from pigeons, or better yet, the lady who fed the pigeons, some thought. Others, like Stouffer, wondered if they’d been attacked.

For months, the lab work continued back in Atlanta, with scientists running tests and reviewing samples. By November of 1976—more than three months after the Legionnaires’ convention—Congress grilled health leaders in a national hearing over their failure to solve the mystery. They were criticized for taking too long to mobilize, for a lack of coordination, for missing evidence.

“It was very unpleasant,” said Fraser.

The outbreak was the final, fatal straw for the Bellevue Stratford, Philadelphia’s grand hotel. Already in financial trouble, it closed that same month, marking “the end of an era,” said Hornstein.

There was no other hotel like that,” he said.

(It would be restored and reopen several years later).

A critical second look

Then, around Christmas, four months later, investigators finally caught a break.

One of the scientists working on the outbreak, Joseph Mcdade, was out at a holiday party and “was berated by somebody who said the CDC had screwed up…and that got him a little upset,” recalled Fraser.

He went back to the lab, as he often did at the end of the year, reviewing material and rerunning tests. This time, he focused on looking for something he didn’t recognize, likening the process to searching for a missing contact lens on a basketball court with your eyes four inches away from the floor.

McDade then zeroed in on a detail he had brushed off before—unusual liver activity in some of the animal specimens that he had attributed to an error. He repeated the tests, aiming to recreate the illness and what had caused it. Part of that involved inoculating guinea pigs with tissue samples from the lungs of people who’d died, injecting that into hen eggs, and taking samples from what grew from that to review under the microscope.

Finally, with the right staining, McDade spotted lots of rod-shaped bacteria he had never seen before. Follow up tests confirmed this bacteria had been the source of the Legionnaires’ illnesses.

“It was a big event,” said Sharrar, the epidemiologist in Philadelphia. The investigative team went from being humiliated to congratulated.

Read the story behind Joseph McDade’s discovery here.

An agent, identified

Scientists would go on to identify the bacteria in samples from victims, they’d confirm effective antibiotics to treat the disease, and they inferred that the source of the bacteria likely came from the hotel’s cooling system, located on the top of the 19-story building.

The bacteria, Fraser explained, naturally occurs in the environment, but it does especially well in warm weather and man-made water sources. That would have made the conditions of the summer of 1976 ripe for an outbreak.

Meanwhile, cooling systems produce a mist as a byproduct of the cooling process. If it’s contaminated with the bacteria “that mist can come across the edge of the roof and layer down the side of the building,” said Fraser. It would then expose people on the sidewalk and, in this case, get sucked into the lobby through a vent near the ground floor, exposing people there.

Future Legionnaires outbreaks would also be linked to cooling systems. It means buildings can help prevent the problem by disinfecting and monitoring them. Scientists realized the bacteria had been responsible for previous unsolved outbreaks, too, including one in Pontiac, Michigan a few years earlier, where scientists noted the cooling system was the source of whatever agent had caused the illnesses.

Dr. Robert Sharrar and Dr. David Fraser stand in front of the Department of Public Health, years after they worked together to solve the mysterious outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

In the public health community, the story of Legionnaires’ disease has turned into a sort of poster child for the power of epidemiology, that shoe-leather detective work involved in mapping out patterns and understanding how diseases move and strike.

These would be critical tools for Dr. Sharrar and others just a few years later, in the early 1980s, when a mysterious disease called AIDS would explode into the American consciousness.

“We knew a lot about the epidemiology of the disease, how it was transmitted long before we found the agent that caused it,” recalled Sharrar.

Philadelphia would be an epicenter in the fight, and Dr. Sharrar would play a key role.

But nearly 40 years after its discovery, Legionnaires’ disease also serves as a reminder of the complexities of investigations and how tricky diseases are. Mother nature can throw all sorts of curve balls. Diseases are often a step ahead.

“I’d say the biggest takeaway was there are infectious agents out there that we don’t know about,” Fraser said. “There are a lot of agents that are being discovered. And that’s humbling.”

Figuring it all out, managing the science and the politics, can be messy. Going back to the Legionnaires example, scientists technically weren’t actually able to identify the original bacteria in the hotel’s cooling system. That’s because by the time scientists had figured out how to test and grow the bacteria in the environment, many months later, the hotel’s cooling system had already been cleaned out.

Fraser and Sharrar don’t lose sleep over this, pointing to all the epidemiological evidence.

A culprit still at large

The discovery of Legionnaires’ disease also didn’t lead to its demise. It’s a tricky bacteria and scientists have learned it’s not just a cooling system problem. The CDC estimates there are thousands of cases of the disease annually, as many as 8,000 to 18,000.

A recent report found that cases are going up, and that the culprit is often found in other potable water sources, not just heating and cooling systems.

“Sort of the dirty little truth is that Legionnaires’ disease is happening all the time,” said Janet Stout, a microbiologist and director of the Special Pathogens Laboratory in Pittsburgh, Pa. “The problem has been that people have not recognized the risk of legionella in these water systems.”

Just because the bacteria is present doesn’t mean its infectious, according to Stout. It has a low infection rate, and only poses a risk when it becomes aerosolized as a mist and a person inhales it. Even so, she says scientists have since learned about how factors in buildings – like their drinking water systems – and the characteristics of people in them, can increase its infection potential.

“To this day, patients still get Legionnaires’ disease from exposure to legionella bacteria in hospitals,” she said.

Which means that nearly 40 years later, the name of the disease and its recurrence serves as a constant reminder to those with ties to 1976.

“Because a lot of friends got sick and passed away. The Legion convention has never been the same,” said Stouffer, who’s still active in the American Legion.

Stouffer says he’s moved on but he hasn’t forgotten. And while the name of the disease was controversial at first, some, like him, have come to embrace it.

“I had no real feelings about it because it happened to Legionnaires, so leave it at that,” said Stouffer.

New industry standards for prevention

While scientists discovered the Legionella bacteria four decades ago, it wasn’t until last year that the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE), the main industry group, came out with standards for preventing the bacteria and outbreaks in buildings.

Scope of Standard 188

- Provides minimum Legionellosis risk management requirements for the design, construction, commissioning, operation, maintenance, repair, replacement and expansion of new and existing buildings and their associated water systems and components.

- Applies to human-occupied commercial, institutional, multi-unit- residential and industrial buildings, excluding single-family residential buildings. Certain building water systems or parts of building water systems may be exempt only where specifically noted in the standard.

- Intended for use by owners and managers of human-occupied buildings, excluding single-family residential buildings. This standard is also intended for those involved in design, construction, installation, commissioning, operation, maintenance and service of centralized building water systems and components.

Source: ASHRAE Fact sheet on Standard 188

“We are many, many years behind Europe and other countries in this regard,” said Stout, who was part of the committee that developed the new industry standard.

Stout says the key to prevention is knowing whether the bacteria is present in building systems or not. That involves regular testing and monitoring.

ASHRAE’s 32 voting member committee, which included representatives from the CDC, the Association of Water Technologies, and the American Society of Health Care Engineers and others, spent 10 years developing the new standard. It’s written in “code-compatible language” making it easier for agencies and jurisdictions to adopt it and turn it into regulations.

“It’s a very big deal,” said Bill Pearson, who recently retired after 40 years of working in water treatment and was part of the committee (Pearson now works with Stout at the Special Pathogens Lab). “Even though it’s not a law or required, it represents a standard of care.”

The standard is not prescriptive, he explained, in that it doesn’t outline specifics on how exactly to prevent the bacteria or treat water systems.

“There’s no one strategy,” said Pearson. “Everyone wants a definitive, specific answer, like ‘oh I have legionella, I can get a shot of anti-legionella.”

But, he said, that just doesn’t exist. Instead, the new standard outlines a roadmap for a risk management process. It’s multi-faceted and involves regular cleaning and maintenance of cooling towers. For example, are the drift eliminators working correctly? These are parts of the system that prevent any mist from seeping out and being inhaled.

“You have to assemble a team to do analysis of the water systems, develop control strategies, verify that you’re implementing them, and then validate that the control strategies are effective,” explained Pearson.

There are no official federal rules for Legionnaires’ disease. OSHA has recommendations for how to respond to possible cases. But the CDC backs the ASHRAE standard and recently came out with a tool kit for water managers.

Most notably, New York City adopted parts of the standard last year, after experiencing its worst outbreak in history. Enforcement of Local Law 77, as it’s called, began this spring. The city now requires buildings with cooling towers to register them, show evidence that they’re maintaining, testing and if necessary, treating them. They must pass quarterly inspections.

“The important thing is awareness and controlling the growth of bacteria in these water systems,” said Stout. “If we do that successfully, then people can relax and know the danger has been controlled. The problem is ignoring the problem.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.