Still life: Art in the service of science

ListenIn the early part of the American nation, science and art were brothers born to the mother of necessity.

Charles Wilson Peale was a prominent painter in Colonial Philadelphia for whom most of America’s founding fathers sat for portraits. After the American Revolution, he indulged his interest in science, organizing the first official U.S. expedition into the New World and creating his own museum of its flora and fauna.

His sons became artists and scientists. His youngest, Titian Peale, collected butterflies. Thousands of them are now in the archive of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Young Peale patented an ingenious way to display his collection: a box resembling a book, with a leather spine and embossed cover, which could be shelved like any other. Bound inside the covers is a hermetically sealed glass box with pinned butterflies. The butterflies were gently toasted to kill feeding pests, and vaccuum-sealed inside the box. Viewers can examine the specimens from above or below, by turning the book upside down.

He made hundreds of these butterfly boxes, meant to fit into any gentleman scientist’s wood-paneled library.

“He didn’t invent book boxes, but to make it look like a book – with binding and marble paper and the text block being the insects – is all him,” said Greg Cowper, curatorial assistant in the Academy’s Department of Entomology.

Insect collections are normally arranged in rows and columns representing scientific categorizations. Peale preferred to arrange butterflies as circular mandalas, or in a kaleidoscopic pattern determined by the size and color of the insect. Each insect is meticulously labeled by species and location.

“This is a certain locality – this is Cuba,” said Cowper, holding a box containing Cuban moths, including the Ascalapha odorata, or the Black Witch. Next to it is a more traditional butterfly arrangement.

“He’s mixing families and types of insects in one aesthetically pleasing arrangement, whereas that is a stamp collection trying to get all the species in the correct spot,” said Cowper.

A short walk from the Academy of Natural Sciences is the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where paintings Titian Peale’s older brother, Raphaelle, are on display. He was America’s foremost still life painter, specializing in painting objects like fruit, vegetables, game, and dishware arranged carefully on tables.

Many of his works are included in “The Art of the American Still Life,” an exhibition making the case that science and art played an essential part in the creation of a uniquely American culture.

“The project of American art after the Revolution was to find American identity,” said curator Mark Mitchell. “To assert themselves [Raphaelle and his brother Titian] as artists, and to recognize a shared culture among Americans.”

America had a vast range of species of plant and animal that were largely unknown to Europe, which American artists and scientists used to leverage cultural and economic independence from Britain. Thomas Jefferson forever sought evidence of an American lion he believed was physically superior to anything found in Europe or Africa. (That such a creature never existed did not deter him.)

By the same token, Raphaelle Peale painted objects that would bolster American prowess. His “Still Life with Strawberries and Ostrich Egg Cup” (1814) shows a plate of wild domestic strawberries arranged next to exotic ceramics from Asia, Europe, and Africa, symbolizing America’s global reach.

Peale also painted homely scenes. “Still Life with Dried Fish” (1815) features a herring and onion surrounded by common earthenware crockery, taking pride in the simplicity of American life.

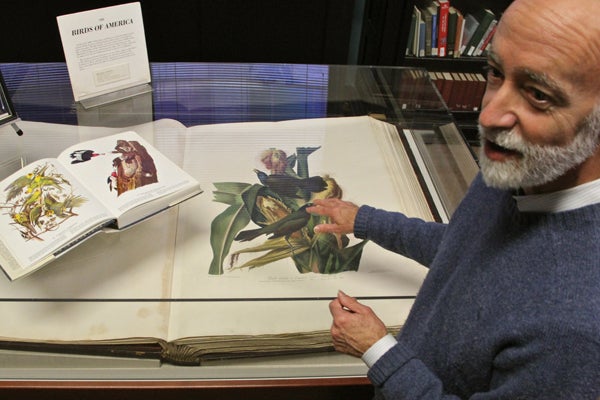

The task to catalogue all that made America unique and present it as boldly as possible, rested on John James Audubon. The ornithologist traveled all around America to record every bird species it contained, illustrating each life-size in his gargantuan Birds of America volumes.

“Four hundred and thirty-five plates. It is a majestic undertaking. Like very little else in all of human history, in scale,” said Mitchell. “What’s he’s trying to do is record American nature – define it. Like a dictionary, trying to understand the character of America.”

While Audubon was as exacting as possible—he personally hovered over the printer’s shoulder to make sure the birds’ feathers were accurately colored—he was also a showman. Birds of America was a tremendously expensive endeavor. He periodically sent packs of five illustrations to subscribers, as he finished them. Audubon needed to wow customers to keep them subscribed to the ongoing project.

Most taxonomical portraits of birds look like mug shots, with a front view, a profile, and some detail of feather patters. Audubon knew his pictures had to be to be so stunning that subscribers would want to hang them over their sofa and show them off to their friends.

“When you look at the Carolina Parrot, you recognize a massive contrivance,” said Mitchell of the portrait of seven parrots in a cocklebur bush. “You see the same bird wired up to see different angles, so you can see all parts of the male, female, and adolescent. And he does that with the same bird.”

Audubon’s project did not sit well with 19th Century scientists. When he approached the Academy of Natural Sciences in 1826 to ask for membership and financial support to complete the book, he was rejected.

“Whenever Audubon was criticized by the scientific community for not knowing the science, he said, ‘Ah yes, but I know the birds from life,'” said Robert Peck, Senior Fellow at the Academy. “‘You might know the birds from a dead specimen, but I’ve seen them feeding their young, catching prey, flying from branch to branch.'”

Audubon eventually was accepted as a member scientist, and his Birds of America is now given pride of place in the Academy library, prominently displayed directly beneath a framed portrait of the board member who rejected it in 1826.

Leaving the book, Peck opens the locked doors to the back-room archives where the Academy has gathered thousands of paintings and drawings over its 200-year history.

“Most people don’t expect the Academy of Natural Sciences to have an art collection,” said Peck. “In the 19th Century, art and science were closely aligned. Scientists had to draw their subjects to convey their subjects. Over time, art and science have gone in different directions.”

He pulls out an original copper printing plate from Audubon’s Birds of America. Audubon’s widow, in need of cash, sold all 435 plates to a scrapper for the value of the copper. As Peck explains, a man at the smelting plant recognized their artistic worth and grabbed as many as he could, about 30 plates. The rest were melted down.

If one gets an opportunity to rummage through the stacks of a natural science museum, one is a fool to pass it by. Among Peck’s favorite are works by Robert Mengel, a professor of ecology at the University of Kansas in the 1970s and 80s. He also maintained an art studio where he drew birds studies for publications like Birds of Kentucky and The Handbook of North American Birds. Many of his originals are in the Academy’s collection.

“Some became still lifes,” said Peck. “Here’s a young bird perched on a flyswatter. By putting the flyswatter in the picture, it gives scale to the bird. That’s very important to figuring out just what it is.”

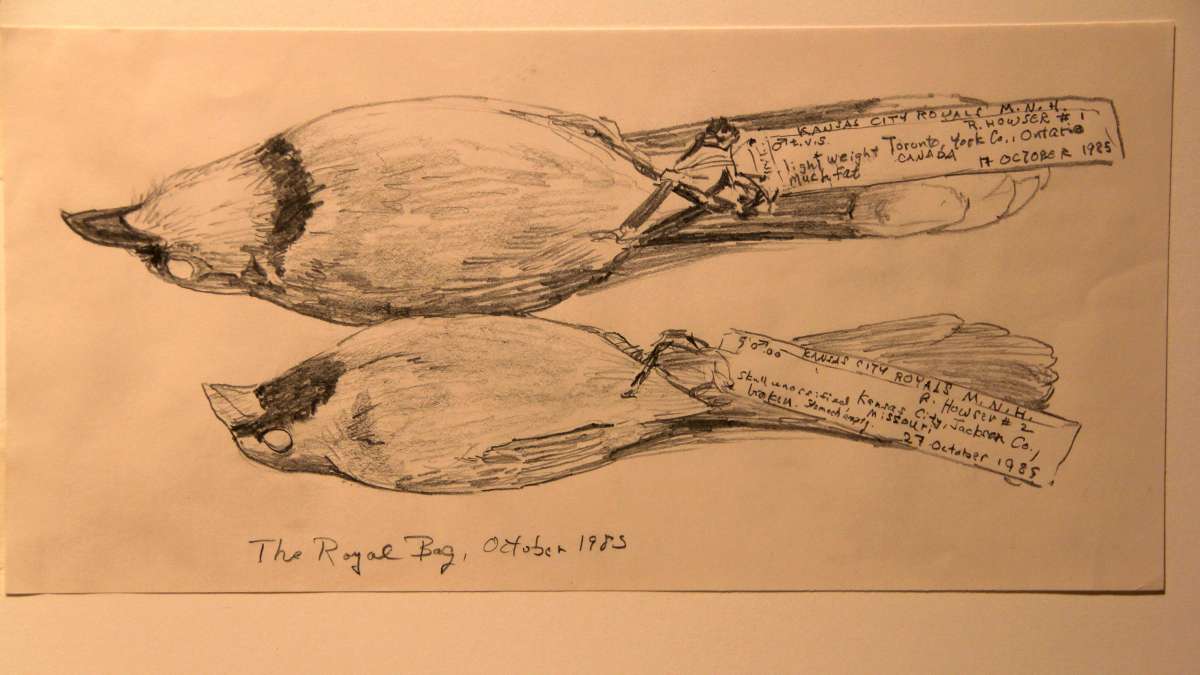

Mengel also had a sense of humor. In 1985 he drew a scientifically accurate illustration of a dead Cardinal, next to a dead Blue Jay. Each has a tag tied to its foot with data about the specimens: “Lightweight,” “Skull Uncalcified,” “Stomach empty.”

In 1985 the Kansas City Royals defeated the Toronto Blue Jays to win the American League Championship, then went on to defeat the St. Louis Cardinals in the World Series, four games to three. Mengel titled his illustration “The Royal Bag.”

Deeper into the archives, Peck swings open a door revealing scores of framed paintings hung on swinging storage racks. Some are abstract landscapes by Mengel. Some are watercolors by another ornithologist, Robert Verity Clem, a little-known painter who made a big splash in 1967 with his illustrations for Shorebirds of North America, considered a definitive ornithological field guide.

Clem lived on the coast of Massachusetts, somewhat reclusively, painting birds all his life. He died in 2010. His work is often compared to that of Andrew Wyeth.

“Both have a shared aesthetic of the East Coast. They saw light and landscape in similar ways,” said Peck. “Where Wyeth would have had Christina on the grass in front. Clem chose a bird instead.”

Shorebirds of North America was Clem’s first and only publication. He was frustrated by the result. A stickler for accuracy, he hated how the editor cropped his paintings, and believed the printing process could not recreate his colors correctly.

“He didn’t like the way the reproductions were done. They weren’t true to his original watercolors,” said Peck. “The watercolors are so subtle; if you put them side-by-side you can see the difference.”

The irony of Clem’s career is that, after the publication of Shorebirds of North America, he never worked in a scientific capacity again. In his eyes, science wasn’t true to life.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.