Why Democrats are angry at Wall Street

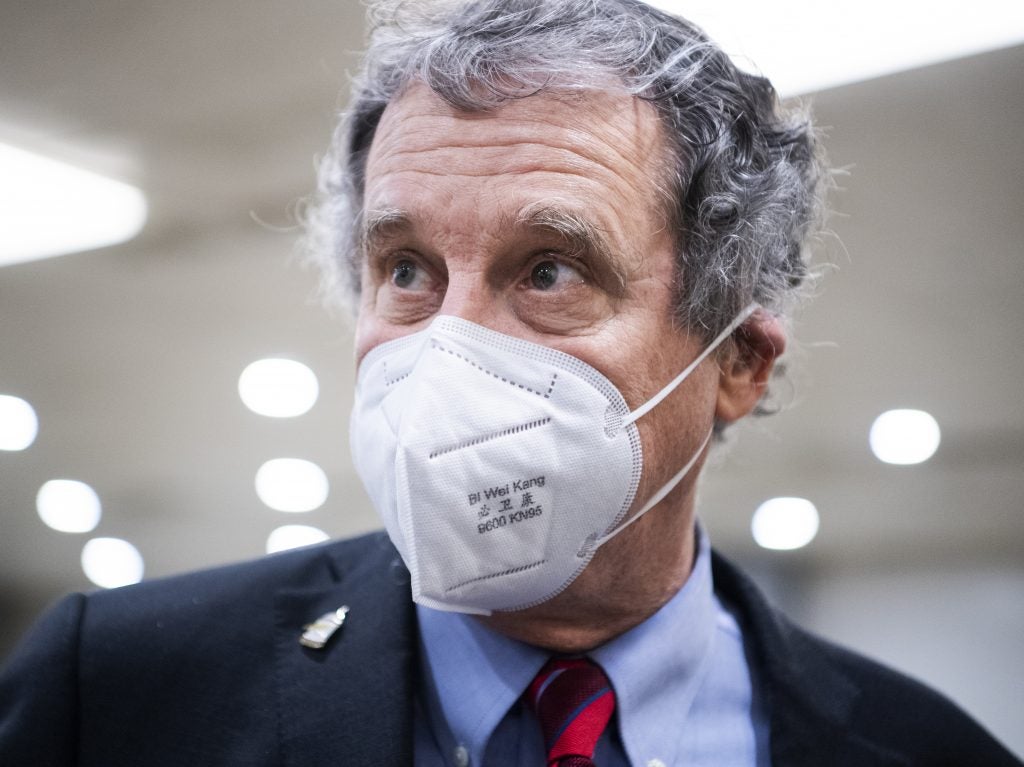

A house under foreclosure in Las Vegas displays a sign on Oct. 15, 2010, saying that it's now bank-owned. Sen. Sherrod Brown has vowed increased scrutiny of Wall Street banks, in part after a surge in foreclosures in his hometown in Ohio over a decade ago. (Mark Ralston/AFP via Getty Images)

Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, hasn’t forgotten the Great Recession.

In the first half of 2007, Brown recalls, there were more foreclosures in his hometown than anywhere else in the country. It was a period that led to the Global Financial Crisis: Millions of Americans lost their homes, while banks and other corporate sectors were rescued by billions of dollars in bailouts.

More than a decade later, Democrats control the White House, the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. House of Representatives, and Brown and fellow populists like Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and Rep. Maxine Waters, D-Calif., are in powerful perches to oversee the big banks.

And Brown, like many of these top Democrats, believes that too many Americans are still getting the short end of the stick.

“They never get bailed out,” Brown says in an interview with NPR. “They never get a second chance. They’re just not in a position in an economy like this, where Wall Street writes the rules, where they can get ahead.”

That anger has been magnified at a time when banks have seen their profits soar during the pandemic, in part, thanks to strong actions by the Federal Reserve to support markets.

And top Democrats believe they are justified in pushing for change at big banks.

They want to push the country’s largest financial institutions to be agents of social change. And they have specific goals, like expanding access to loans and impose fewer fees for average Americans, or more outreach to unbanked and underserved communities.

“They did very well during the pandemic,” Brown notes about the banks. “We’ve seen stratospheric compensation levels. We see stock buybacks and dividend distribution. Yet, wages throughout our economy are essentially flat.”

Brown is the chairman of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, which also includes Warren, another Democrat with a reputation for being tough on Wall Street.

The Massachusetts senator played a key role in the creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.

“You know, most people think of Congress in terms of passing legislation, and yeah, that’s part of the job,” she tells NPR. “But the other part of the job is oversight.”

That was in evidence when Brown’s committee this past week brought in the chief executives of the country’s top six banks for questioning as part of an annual oversight.

During that hearing, Warren asked Jamie Dimon, the chairman and CEO of JPMorgan Chase, about overdraft fees the bank charged its customers during the pandemic, which she estimated at nearly $1.5 billion.

The heated exchange ended when Warren asked Dimon if he would volunteer to refund that money. He declined.

Warren is unapologetic about pushing banks to do more given their roles as critical institutions in society.

Bank executives, Warren says, “have a responsibility to execute on making their banks part of the solution to our economic and racial problems across this nation.”

But Republican lawmakers disagree with that very premise. They criticize executives for comments they have made — about voting rights, in particular, and they are critical of companies making business decisions based on environmental considerations.

“That ought to be left to elected lawmakers,” says Sen. Pat Toomey, R-Penn., the ranking Republican on the Senate Banking Committee.

Bankers aren’t naïve to the politics at play. Democrats have a small majority in the House of Representatives and a razor-thin majority in the Senate. And the midterm elections are less than two years away.

But even with a change in power in Congress, analysts warn banks are likely to face continued pressure from Democrats — and society — on key aspects of their operations, from whom they lend money to where they invest.

“Banks have no choice but to address these issues, because it impacts their communities, their customers and their employees,” says Mike Mayo, a banking analyst at Wells Fargo Securities. “You have to live in the real world, and the real world has these issues as part of the banks’ businesses.”

That message was made clear by Waters, a California lawmaker in a powerful position to influence banks as chair of the House Financial Services Committee.

“You know, what I have discovered about the banking community is that they have had a way of operating traditionally, historically, and they don’t change easily,” Waters tells NPR.

But Waters adds she will still demand changes on Wall Street.

“I think that many of them have come to understand that I can be dealt with, but I cannot be tricked. I cannot be fooled,” she says.

“And I don’t accept being undermined.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))