States are ratcheting up reading expectations for 3rd-graders

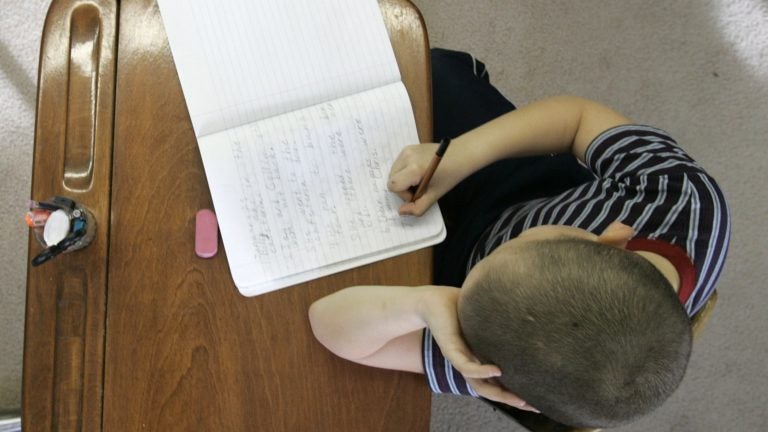

Nineteen states have adopted "mandatory retention" policies, which require third-graders who do not show sufficient proficiency in reading to repeat the grade. (Larry W. Smith/Getty Images)

Changes in education policy often emanate from the federal government. Think Common Core, the set of standards established in 2010 for what U.S. students should know. But one policy that has spread across the country came not from Washington, D.C., but from Florida. “Mandatory retention” requires that third-graders who do not show sufficient proficiency in reading repeat the grade. It was part of a broader packet of reforms proposed by former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush in 2002.

Now 19 states have adopted the policy, in part because Bush has pushed hard for it. Not all children who perform poorly on reading tests are retained: Generally students with special needs and kids who have been in the country less than two years are exempted. And studies have shown that a child’s early literacy skills can have long-term implications. One out of six students who are not reading proficiently by fourth grade, according to a study by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, don’t graduate from high school on time. That rate is four times greater than that of proficient readers.

At the same time, forcing children to repeat a grade is stigmatizing and can damage their self-esteem. Multiple studies have found that flunking a grade makes it much more likely students will fail to graduate from high school. Some parents and educators have organized against mandatory retention and advocate for children to sit out high-stakes exams. A group of parents in Florida unsuccessfully challenged the policy in court.

Professor Marty West at Harvard has found that there are positive short-term outcomes for retained children in Florida. They do better in math and reading and are less likely to be retained in the future. Those benefits, though, dissipate over time: Repeating third grade under Florida’s mandatory retention law makes it no more or less likely a student will graduate from high school. West argues this can be seen in a positive light, because historically failing a grade has been such a strong predictor of dropping out.

Florida’s law also included millions of dollars for supports like reading coaches and summer school sessions. Professor Nell Duke at the University of Michigan points out that the short-term gains could be due to those interventions, rather than retaining children.

Oklahoma adopted mandatory retention in 2014. The policy was not accompanied with large state investments in its schools; in fact, it has one of the lowest rates of per pupil expenditure in the country. And yet, over the past 20 years, it has created one of the most comprehensive public pre-K programs in the country. Seventy-three percent of its 4-year-olds are enrolled.

Policies like mandatory retention have put pressure on teachers to have students reading at earlier ages. At Rosa Parks Elementary school in Tulsa, Okla., where the student body is majority Latino, kindergarten teacher Melanie Metter says English-language learners who didn’t attend pre-K can be at a disadvantage: “Some of them, it’s their first experience in school and their first year with English.”

Conversely, attending a high-quality preschool can be a boon, particularly for students from underprivileged backgrounds. Next door to Rosa Parks is an early childhood center run by the Community Action Project. It’s one of several sites operated by the nonprofit across the Tulsa region. CAP only accepts students whose families are very low income, and it keeps a long waiting list. And while it is funded with state and federal resources, it is also supported by the George Kaiser Family Foundation, which has heavily invested in early childhood education in the state.

Touring the facility, it becomes evident how early education can help prepare kids for elementary school. Class sizes are capped at the facility — there is a maximum of 20 students in the 4-year-olds’ classrooms, and the numbers are even lower for younger ages. Each classroom also has two teachers.

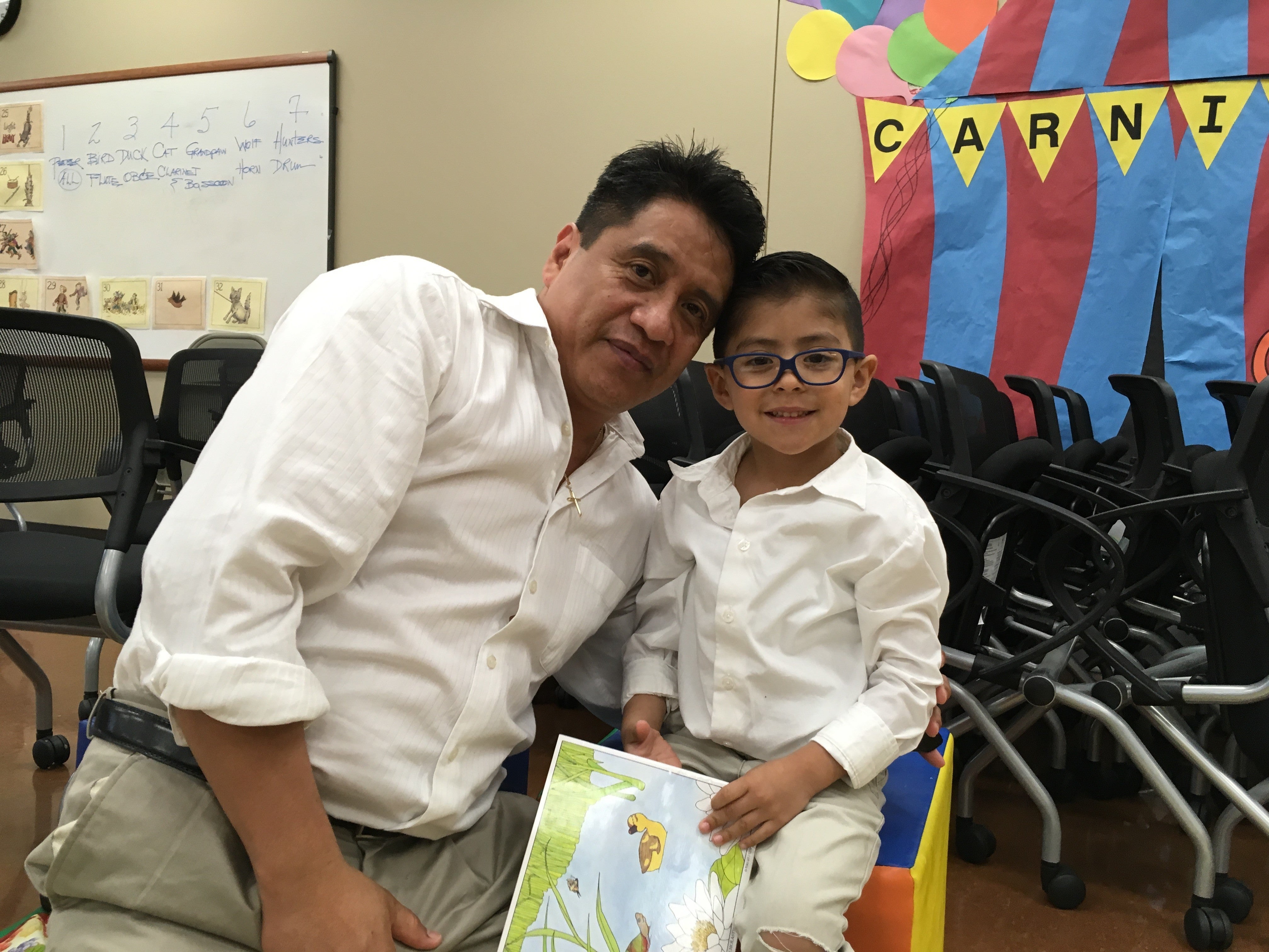

CAP also encourages parents to foster literacy at home. At an event called “Breakfast with Books and Dad” day, families are treated to granola, fruit and yogurt before the start of school. Books are scattered around the room and families can take them home.

At a breakfast this spring, Hector Peña read with his 3-year old on a rug, quizzing him on colors. “¿Este de qué color es?” he asks his son. What color is this? “¡Amarillo!” (yellow) his son answers.

Diane Horm, a professor of early childhood education at the University of Oklahoma, says that programs like CAP can seem an anomaly in Oklahoma. “The fact that it is the state of Oklahoma — that has a reputation for struggling with public education and other social services — to have this program is kind of a unique contrast,” she says.

The fact that Oklahoma’s approach of ratcheting up expectations for students without making bigger monetary investments in schools frustrates Pedro Noguera, a professor at UCLA who has studied the experience of students of color in the public school system. As he points out, when children in affluent families have difficulty reading, their parents can hire outside specialists offering intensive, personalized services. “It starts with diagnosing the learning need,” Noguera says. “And then developing a response tailored to the needs of that child.” Poor families can’t afford that.

Noguera sees a disconnect in the increased expectations and flat school funding. “We often hold kids accountable,” he says. “In this case, with retention. We hold teachers accountable for not raising test scores. But the state legislature doesn’t hold itself accountable for putting the resources in place to make sure schools can meet the learning needs of kids.”

Freelance journalist Alexandra Starr reported this piece as a Spencer fellow in education reporting at Columbia Journalism School.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))