Sometimes it takes a ‘village’ to help seniors stay in their homes

People are seen walking past the "You Are Beautiful" sign, an art installation by Matthew Hoffman, in the Englewood neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. Nearly half of the people in this African American neighborhood live below the poverty line and many seniors have no idea there are public services that might help them. (Kristen Norman/NPR)

The idea of being able to maintain independence into one's 80s or 90s is so irresistible that he number of villages across the country has grown to 230.

Debra Thompson is throwing a block party. She has good weather for it — never a sure thing in Chicago — a warm and sunny autumn afternoon. Music is playing, hot dogs are grilling.

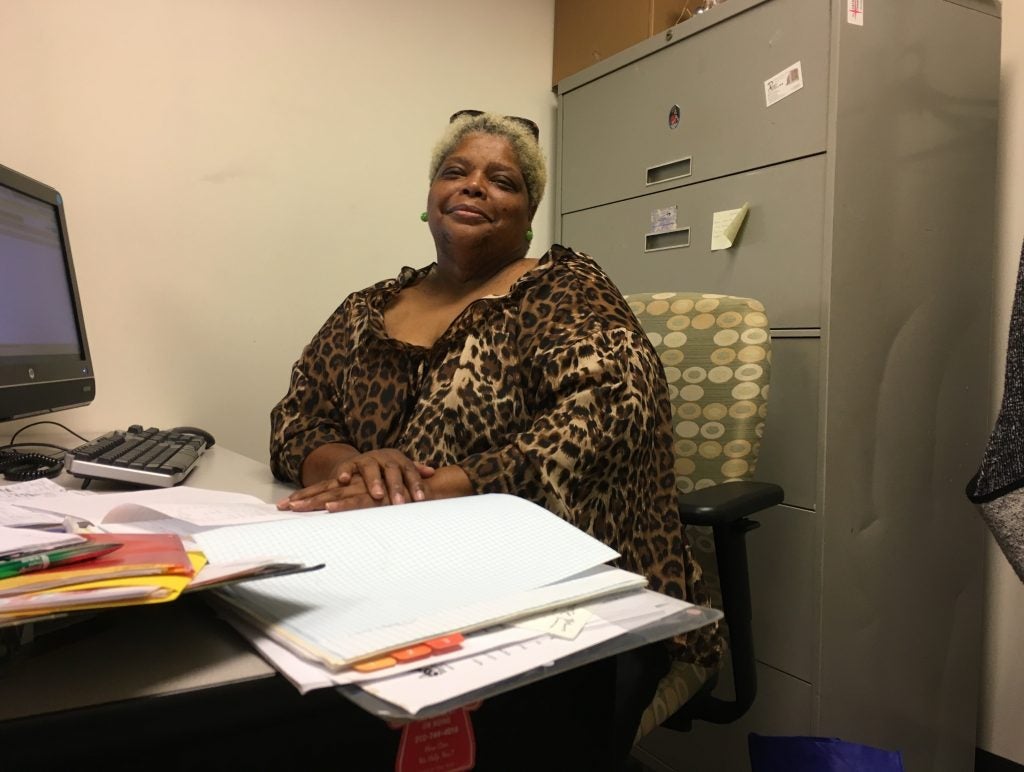

But this party isn’t just for fun. Thompson is the volunteer chairwoman of Englewood Village, an organization that connects low-income older adults on the city’s South Side with services from nutrition to job assistance to home repair. And this is how she is reaching out to potential new members.

“We have flyers, we’re going to knock on doors, spreading the word, getting everybody involved,” says Thompson with her usual boundless enthusiasm.

The Englewood Village has been around since 2015. But its roots go back 17 years and all the way to Boston, where Susan McWhinney-Morse and her friends were grappling with anxieties about aging. They wanted to stay in their homes as long as possible. They wanted to remain in their community on Beacon Hill.

After a couple of years of effort, they produced the concept now known as the village. It’s a membership-run organization that provides access to services like transportation, help with household chores, even trouble-shooting computer problems, along with classes and social activities.

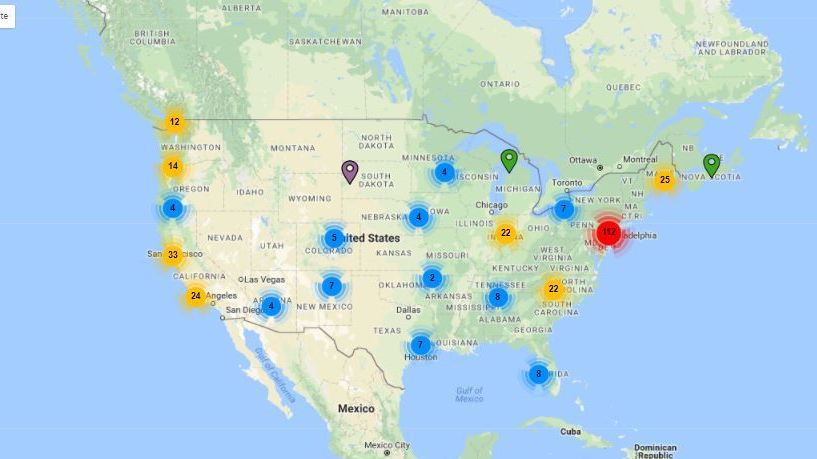

The idea of being able to maintain independence into one’s 80s or 90s is so irresistible that over the past decade, the number of villages across the country has grown from just that one in Boston to 230. Another 130 are in development. An independent organization has been founded to support the expansion of villages. It’s called the Village to Village Network, which has a map on its website showing where villages are located.

So far, the overwhelming majority of village members are middle class or wealthier, according to research from The Center for the Advanced Study of Aging Services at the University of California, Berkeley. That may have something to do with membership dues amounting to several hundred dollars a year. But now the idea is being adapted to serve more varied communities, where dues are not an issue.

Our reporting was inspired by NPR listeners. Earlier this year, we asked them to share their stories of how older adults without family caregivers manage when they need help. Many respondents mentioned the villages in their own communities.

So this fall, we traveled around the country to take a look at how villages are evolving. We found an effort in Chicago to create villages that serve low-income communities of color. We found a village in rural California where older adults don’t just receive services, they also provide them. Ultimately, what we found was that in practice, the village model isn’t so much a fixed formula, as an expression of older adults’ desires to age with dignity and independence.

Or as Susan McWhinney-Morse put it, “a grass-roots movement on the part of older people who did not want to be patronized, isolated, [or] infantilized.”

Changing expectations

McWhinney-Morse says that back in 2000 in Beacon Hill, continuing to live independently wasn’t expected after age 65.

“That was the line when one became suddenly old,” she says. “I knew from everything I read that it was the time when I should move: Move south, move flat, move warm, move safe, but certainly not stay in my house on Beacon Hill.”

But who wouldn’t want to stay in Beacon Hill, with its colonial-style architecture, cobblestone sidewalks and charming little shops? So McWhinney-Morse and about a dozen friends tried to find a way to get the support they needed as they aged without having to give up their homes and their community.

The result of two years of effort was Beacon Hill Village. Members pay dues of a few hundred dollars a year. In exchange, they have access to a wide array of discounted services — from home health to home repair to transportation. There’s also a busy calendar of classes, trips and social events.

There was nothing else around like Beacon Hill Village for several years. Then around 2006, it started to get a little bit of media attention. A little bit was all it took. McWhinney-Morse says that in one single week, “we literally — this is not an exaggeration — received 1,000 telephone calls or emails from across the country from people saying, ‘How do I start a village, is there a village in my neighborhood, what do I do, who can I call, may I come and see you?’ ”

Beacon Hill Village is no longer novel. It has been around for 15 years and has more than 300 members. And every Wednesday morning for nearly a decade, at least a dozen of them have met to discuss politics over French toast and oatmeal.

Observations about climate change, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program and President Trump’s latest tweet rise above the clink of cutlery and coffee cups.

“It’s made me much more alert,” says 80-year-old Muriel Feingold. “I have to keep up with stuff because [I know] I’m meeting people on Wednesday. So I think I’ve been more attuned to what’s going on politically and internationally.”

Beacon Hill Village is also providing the kind of help with daily activities that was part of the original vision. Like rides to the supermarket. Tom Moore, 67, drives several days a week for Beacon Hill Village members. He used to be in the travel business. This is his retirement job.

He doesn’t do it just for the money. “I enjoy it,” he says. “I meet a great group of people.”

One of them is 83-year-old Joan Smith. She emerges from her apartment building slowly, using a cane. “I have a problem with balance if I go too fast,” she says.

“I didn’t want to use it,” she says of her cane, but the Beacon Hill cobblestones can trip her up and the cane does seem to help.

So the ride to the supermarket is essential for her. It’s also fun. Smith enjoys getting her own groceries, checking the specials, seeing what’s new. But that’s now beyond what 77-year-old Cynthia Beaudoin can do. Moore picks up her groceries from a list and delivers them to her apartment.

A home health aide greets him at the door. Beaudoin remains on the couch, her walker nearby and an emergency call button hanging around her neck. Her life has been like this since she was in the hospital a few years ago.

When she was discharged, she didn’t want to go to a rehab hospital. “I just wanted to come home directly,” recalls Beaudoin.

Beacon Hill Village was able to connect her with the right services to make it possible for her to return to the apartment she has lived in for 36 years. It has a view of the Charles River that no one would want to leave.

But for Beaudoin, Beacon Hill Village is more than the sum of its services. “It’s comforting,” she says. “That’s one of the most important things.”

A village for everyone

At her Chicago block party, Debra Thompson cannot be ignored, with her dyed blond hair and a bright yellow T-shirt. She calls out to everyone, hoping they’ll fill out her survey so she can find out what they need. And Englewood seniors have a lot of needs. Nearly half of the people in this African-American neighborhood live below the poverty line. But many of them have no idea that there are public services that might help them. Thompson wants to change that.

And she persists even when some people are reluctant to put their names on anything.

A woman named Bessie Stovall says, “My children say don’t sign nothing unless I know what I’m signing.”

Thompson reassures her. “This is not a contract.” She explains that Englewood Village can connect her with services to help find a job, for instance, or a place to stay. “Oh yeah, I need a job,” says Stovall. Suddenly, she is happy to fill out the form, and Thompson directs her to an upcoming job fair that focuses on employment for seniors.

Thompson also passes out information on a lottery for free roof repairs and discounts on utilities and tells people about a service that can help frail older people remain in their homes.

Frances Shedd, 80, knows all about that one. Years ago, she worked for a government service that provides homemaker assistance to older adults up to 12 hours a week. Now she watches the party from her porch, accompanied by her own homemaker, Quintechette Jones.

“I keep everything clean in her atmosphere,” says Jones. “I make sure she gets her nutrition. I groom her sometimes. And then we sit and chat.”

Shedd thinks it’s great that the Englewood Village is telling more people about this service. “When you get to a certain age,” she explains, “you need somebody to see after you because we don’t feel good when we get up in the morning.”

Another observer of the block party is Joyce Gallagher, and she likes what she sees. She is Chicago’s deputy commissioner for senior services. Gallagher loved the village concept from the first time she heard about it and wanted every older adult to have access to such a supportive community. The hang-up was the dues. The Chicagoans who could benefit the most from a village couldn’t fork over a few hundred bucks a year on top of paying for services.

Then Gallagher had her lightbulb moment. What were the dues for? They paid for office space and computers and phones. But her department already had all of that in its 21 senior centers. The city could donate the office space and equipment. But she didn’t want this to be a city-driven program. She envisioned the villages being grass-roots organizations run by volunteers. As for services, those would come from government programs available to low-income seniors.

So Gallagher began to call meetings at senior centers around the city to see whether anyone was even interested in becoming part of this. She had no expectations about how she would be received. “You have someone coming from the outside, and saying ‘Listen, we’ve got no proof that this is going to work, but we really feel that you deserve this, that every community deserves this … are you interested?’ ”

In Englewood, Debra Thompson was interested. In fact, the Village has become her cause. “I devote every day to my seniors,” she says. “I’m always looking for ways and partnerships and issues that can assist us to assist them in achieving what they need.”

Thompson’s early enthusiasm is the reason that Englewood is the oldest village in the Chicago system. Currently, there are just six citywide. Each one operates out of a different senior center. Gallagher wants to have villages reaching out to all 21 neighborhoods where senior centers are located by the end of next year.

A big dependence on government services could make the project vulnerable to the whims of state and federal budget-makers. But Gallagher says that is not the only focus: Volunteers in each village set their own agendas. One is centered on gentrification, another on preventing financial scams targeting seniors, while a third concentrates on dealing with emotional trauma caused by that neighborhood’s many shootings.

People continued to stop by Thompson’s block party even after the hot dogs were gone. Over the course of the afternoon, she signed up close to 50 people who hadn’t known about Englewood Village. For Thompson, that was one sign that the afternoon had been a success. Another sign? Some people invited her to throw block parties on their streets, making Thompson hopeful that Englewood Village will continue to grow.

Reaching seniors out of reach

Plumas County, Calif., has about 19,000 people spread across an area bigger than the state of Delaware. It’s in the Sierra Nevada Mountains in northeastern California. There’s no interstate highway, not a lot of chain stores, hardly any stoplights, but lots of pine trees.

“When you live out here, you have to be ready for the winter,” says 75-year-old Jimmie Oneal.

And preparing for the snow and cold is what Oneal is doing on this late autumn afternoon. She directs a handful of volunteers who’ve come to ferry stacks of firewood from a garden shed up to her back porch.

That firewood will help Oneal heat her home when the cold is so severe that her propane heater just isn’t enough.

Both Oneal and the volunteers helping her are members of Community Connections, Plumas County’s version of a village. It works on what is known as a time bank model. Members get credits in their time bank accounts for helping one another. Then when they need some help themselves, they draw on those credits to “pay” for the service. And in Plumas County, those services run the gamut from helping to clear trees to serving food at a wedding to teaching welding and other building skills.

Oneal lives alone in a little dome house on a heavily wooded acre of land that slopes down to a creek. Since her husband died eight years ago, help from Community Connections volunteers has been crucial to her ability to remain here. She has still had to make some changes though: She gave up her chickens.

“I was having to carry buckets of water [for the chickens] down that hill in the wintertime and it gets really icy,” she says. “I finally decided that one bad fall could be real bad news for me. So I decided to find homes for my chickens. And I still miss ’em.”

If Oneal had a bad fall, her options in Plumas County would be limited. There’s only one assisted living facility. It can accept just four residents. There are no vacancies. The beds are also full at the two small nursing homes. So around here, helping seniors live independently isn’t just matter of what they want, it’s almost the only option.

And Oneal says she has her own way of contributing to the time bank for the help she receives from Community Connections.

“I guess you could say I’m sort of like a granny. People come to me with all kinds of questions: about gardening, about chickens, about trees, about how to survive with the cold, especially people who haven’t been here that long,” she says.

Community Connections is run by Plumas Rural Services, a large nonprofit social services agency. Dues are just $10 a year. Anyone can join. The youngest member is 7 years old, the eldest is 93.

Leslie Wall has run Community Connections since it began 10 years ago. Back then, she wanted to find out what older people wanted from the program.

“We expected seniors would want transportation,” she recalls, “and they would want visitors, and someone to call them weekly. And what we found was the greatest need of our seniors was to be needed. We have seniors who want things to do that are vital, that matter, that make a difference.”

Pat Evans’ skills as a seamstress make a difference to Karon Chance. Evans, 77, does almost all of the Chance family’s mending, which leaves Karon Chance more time to build her catering business.

Now, Chance believes she has brought Evans a real puzzle. The backing of a cherished old quilt is shredding. It needs to be removed and replaced. But for Evans, it’s no problem. As the two women pore over the quilt, Evans explains what kind of replacement fabric will be needed and a couple of different stitching techniques she could use.

There’s nothing like experience. Evans has been sewing since she was 10 years old: made her own clothes, her wedding dress, her late husband’s sport coats, her kids’ clothes. Now she lives alone and sews for her fellow members of Community Connections. Karon Chance says that has benefited both of them in ways they hadn’t planned.

“Sometimes we just catch up and talk about the dog and about the flowers,” she says. “Pat and I might never have crossed paths if it weren’t for Community Connections. And now I’ve made a friend.”

That is an unexpected dividend of credits in the time bank.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))