Signed, sealed, undelivered: Thousands of mail-in ballots rejected for tardiness

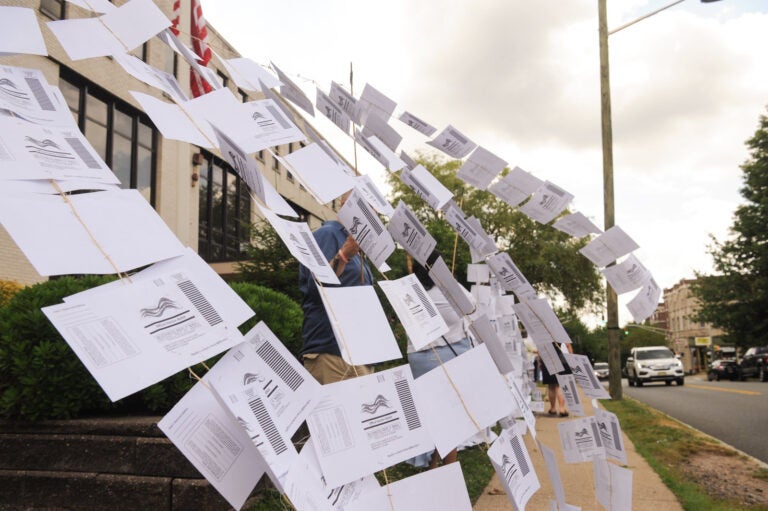

A rally outside the Montclair, N.J., town hall on July 1. Protesters hung 1,101 absentee ballots to represent the number of votes that weren't counted in a mayoral election that was decided by just 195 votes. (Kate Albright/Montclair Local)

Mail-in voting, which tens of millions of Americans are expected to use this November, is fraught with potential problems. Hundreds of thousands of ballots go uncounted each year because people make mistakes, such as forgetting to sign the form or sending it in too late.

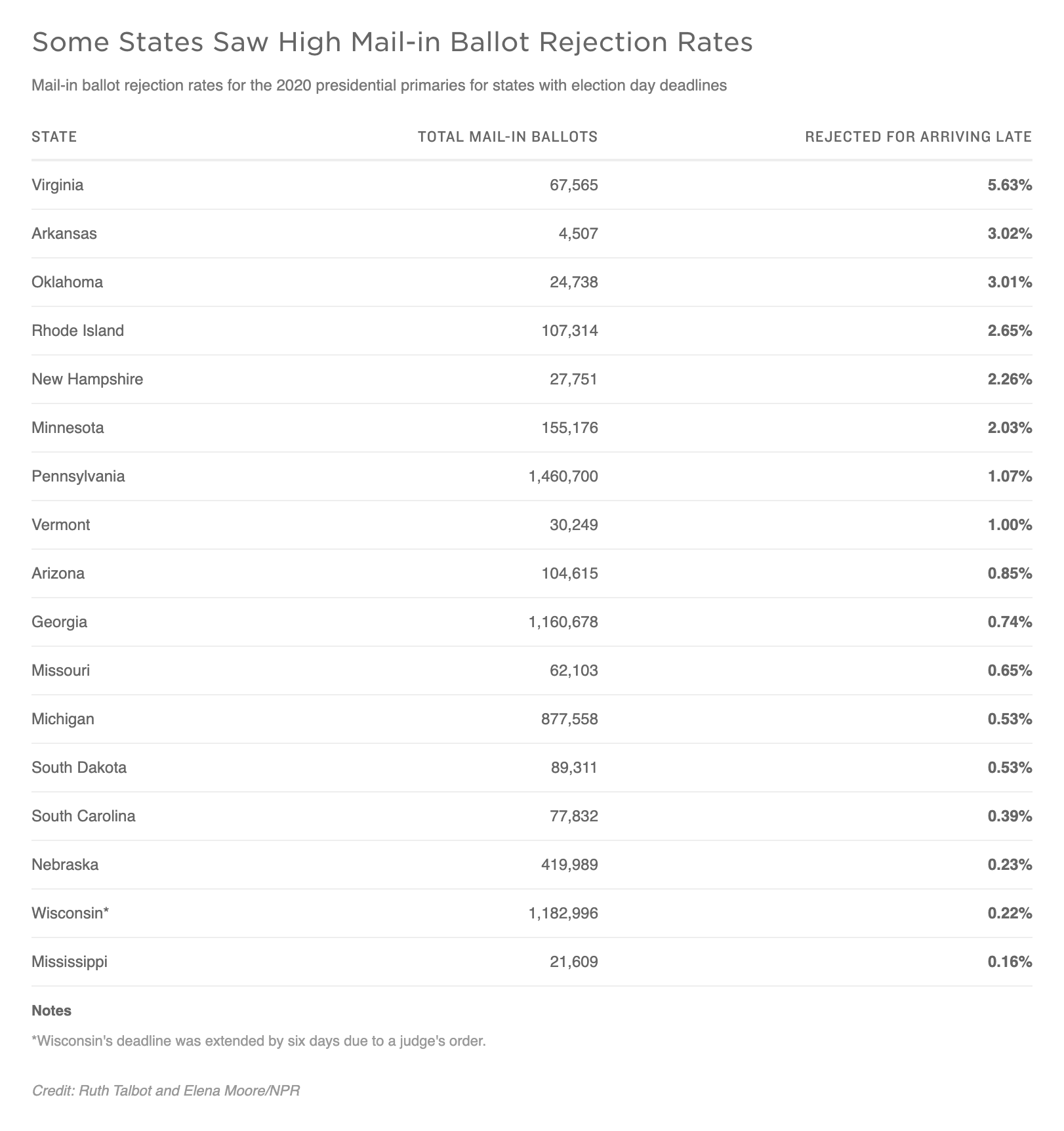

An NPR analysis has found that in the primary elections held so far this year, at least 65,000 absentee or mail-in ballots have been rejected because they arrived past the deadline, often through no fault of the voter.

While the numbers are relatively small — around 1% in most states — they could prove crucial in a close election, especially one in which many more voters are expected to cast absentee and mail-in ballots to avoid going to the polls during a pandemic.

Those who use mail-in voting for the first time — especially young, Black and Latino voters — are more likely to have their ballots rejected because of errors, said Charles Stewart, a political scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies election administration.

”That’s the sort of thing that makes me wary about what’s going to happen in November when we get an even larger influx of people who haven’t voted, or haven’t voted by mail in the past,” he says.

The political parties and voting groups are well aware of what’s at stake and have launched aggressive legal campaigns to try to shape the rules for November.

Democrats and voter advocacy groups have filed suits in at least 10 states, challenging laws that require mail-in ballots to be received by or before Election Day. They’re asking judges to allow ballots to be accepted as long as they are postmarked by Election Day, because of difficulties voters might encounter due to the pandemic and delayed mail delivery.

The Republican Party and election integrity groups are fighting back. They argue that extending the deadline will undermine public confidence in the results, which could be delayed for weeks. They also insist, without evidence, that it will raise the potential for fraud — a position President Trump has taken repeatedly.

In the meantime, voters have been left confused, discouraged and in some cases disenfranchised.

Susie Sonneborn of Montclair, N.J., says she tried to be extra-careful to make sure her ballot was postmarked on time when she voted in a mayoral race in May. But when she heard that more than 1,100 ballots — 9% of the total — had been rejected, she checked with the local election office and was shocked to discover that hers was one of them.

“It was just really disappointing and surprising that by following the instructions that are printed on the ballot, I was set up for failure,” she says. Sonneborn insists that she didn’t see anywhere that her ballot needed to be received within two days of the election to count, which was especially frustrating because the mayor’s race was decided by only 195 votes. Residents held a rally outside town hall the day the new mayor was sworn in, calling for officials to “count every vote” in future elections.

Other states are also reporting large numbers of rejected ballots. More than 5% were not counted in Virginia’s June primary because they arrived too late. More than 1% of the ballots in Pennsylvania and Nevada were also not counted last month for the same reason.

In Wisconsin’s chaotic April primary, 2,659 ballots were rejected for missing the deadline, but the number could have been much higher. About 79,000 ballots were received after Election Day but within a six-day period that was allowed on an emergency basis.

Tens of thousands of other ballots were discarded this year for other reasons, most often because of a missing or mismatched signature. Last week, the League of Women Voters filed suit in New York state, where more than 34,000 absentee ballots — or 14% of the total — were rejected in 2018. The group wants voters to have the opportunity to correct any problems before their ballots are discarded.

The suit is part of a flood of litigation over mail-in voting this year.

Democrats and progressive groups are suing to change the rules in Florida, where 18,504 vote-by-mail ballots — more than 1.3% of the total — were rejected in the state’s March primary for a variety of reasons, including missed deadlines. The lawsuit argues that mail-in ballots should have to be only postmarked — not received — by 7 p.m. on Election Day.

Kirk Nielsen, the plaintiff in the case, says the fate of a ballot is out of a voter’s hands once it goes in the mail. His was one of thousands of ballots rejected in the state in 2018. Nielsen says he mailed it eight days before Election Day, but it was not received until eight days after. He worries about being disenfranchised again.

“I want to vote by mail this year because of the pandemic. I don’t want to get sick at a crowded polling place. That said, I think there’s an even greater risk this year voting by mail that my mail ballot might not be counted, along with thousands of others,” Nielsen says.

His case is scheduled to be heard this month, but Republicans were heartened by the judge’s refusal to issue a preliminary injunction against the state’s mail-in rules.

The judge said the Election Day receipt deadline “eliminates the problem of missing, unclear, or even altered postmarks, eliminates delay that can have adverse consequences, and eliminates the remote possibility that in an extremely close election — Florida has had some — a person who did not vote on or before Election Day can fill out and submit a ballot later.”

These are all arguments that Republicans have made in defense of keeping the Election Day deadline currently in place in most states.

“Allowing massive amounts of ballots to arrive or the counting to continue well after Election Day really allows room for fraud,” says Mandi Merritt, national press secretary for the Republican National Committee. “It allows losing candidates or other partisan operatives to go find more late votes that could potentially change the legitimate outcome of an election and really just leaves room for unnecessary litigation.”

While Merritt did not offer an example, she says even the possibility of fraud would undermine voters’ confidence in the results.

Most election officials would disagree that candidates could “find more late votes” to change the results, but some do worry about extending the deadline for other reasons.

Katie Hobbs, Arizona’s Democratic secretary of state, thinks voters would be confused if the deadline were switched so close to the election, especially in a year when the pandemic has upended voting in so many other ways. She says it takes time to educate the public and to implement such changes, which can be more complicated than people think.

“There’s an assumption that every piece of mail automatically gets postmarked, and that’s just not the case,” says Hobbs. “Our ballots are postage paid, so they’re sent with bulk permits, and oftentimes those pieces of mail are not postmarked.”

Hobbs says having a postmark deadline would require the state to arrange with post offices to provide such postmarks or to come up with another system to track the ballots.

Arizona recently reached a settlement with progressive groups that had sued to extend the ballot deadline. The state has agreed to boost voter education and outreach programs and to encourage other options, including drop boxes where voters can deposit their absentee ballots, to be picked up later by election officials. Hobbs says this option allows voters to get their ballots in on time without risking exposure to the coronavirus at the post office or a polling site.

A number of states have increased their use of drop boxes. But the Republican National Committee and the Trump campaign don’t like that option either. They recently filed a lawsuit against the state of Pennsylvania, arguing that such drop boxes are insecure, are prone to fraud and should be prohibited.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)