Photos day or night: How one photographer documented the segregated South

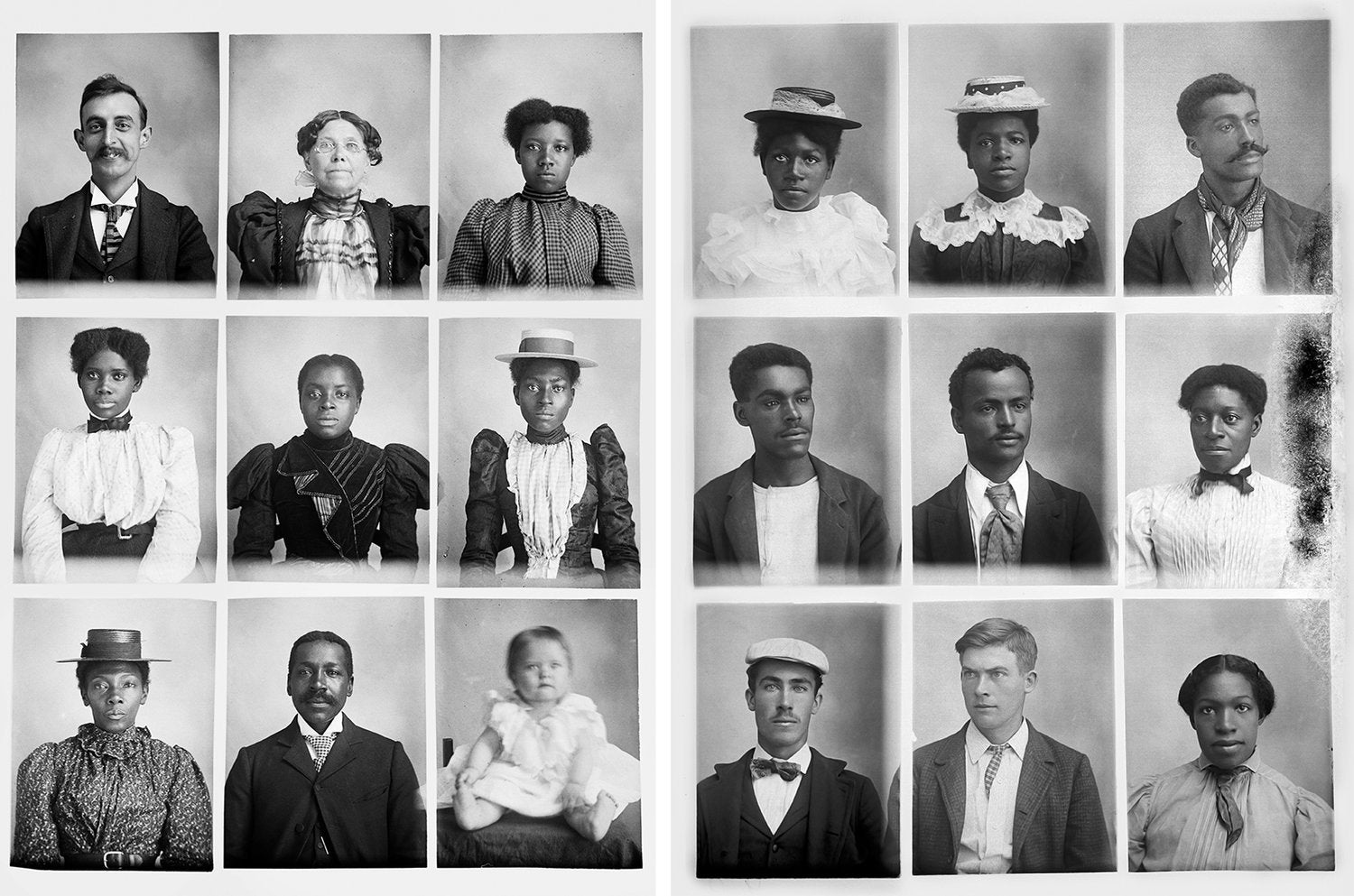

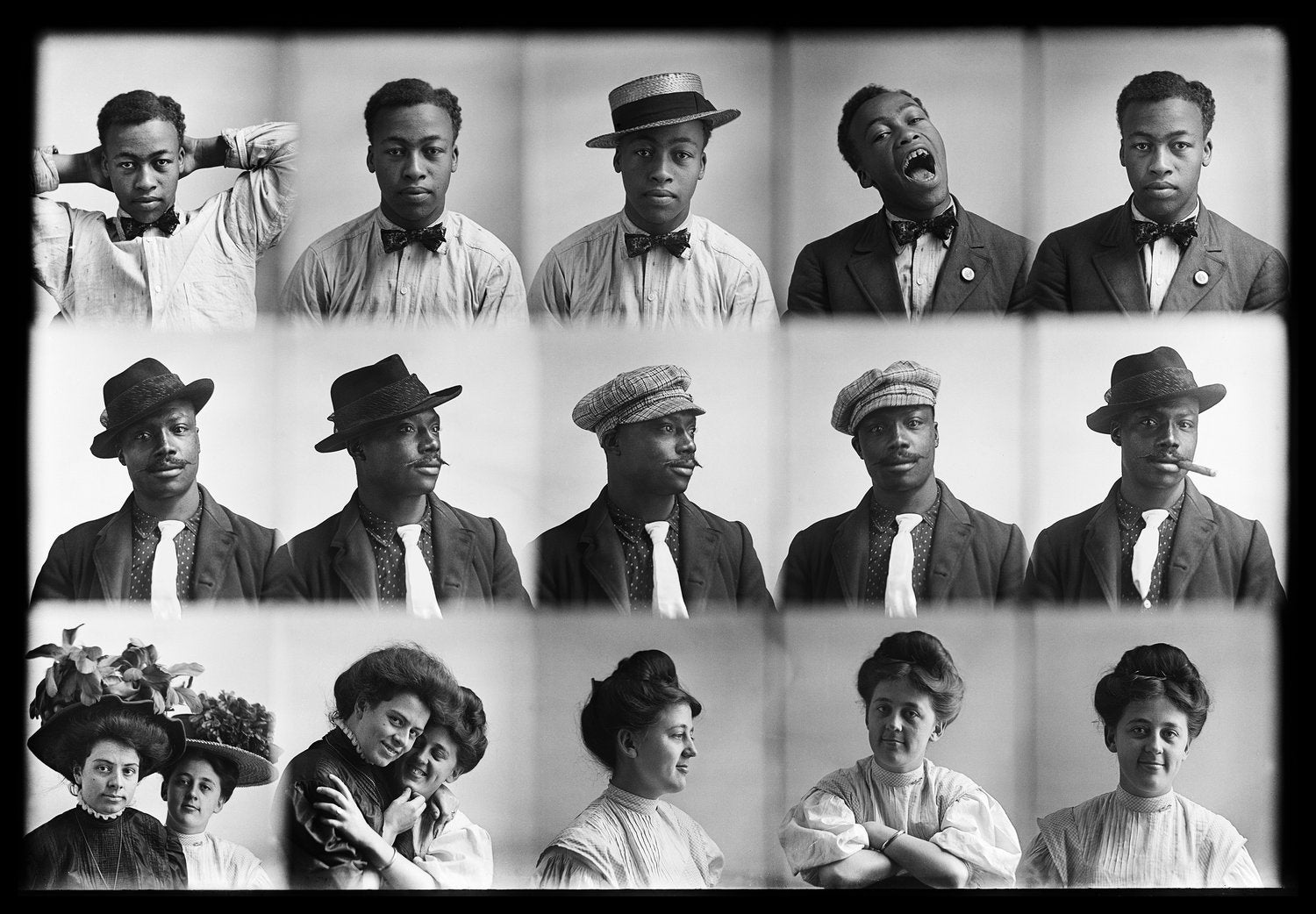

A photograph by Hugh Mangum from Photos Day or Night: The Archive of HughMangum, by Sarah Stacke with texts by Maurice Wallace and Martha Sumler, Hugh Mangum's granddaughter. (Courtesy of Hugh Mangum Photographs, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University)

Monumental shifts were occurring in America during the time photographer Hugh Mangum was working in North Carolina and the Virginias. It was the height of the Jim Crow era, when the nation was starting to see laws separating whites from blacks. But as a businessman who needed to support his family, Mangum didn’t discriminate between clientele, therefore leaving behind an archive that tells a different story of the segregated South at the turn of the 20th century.

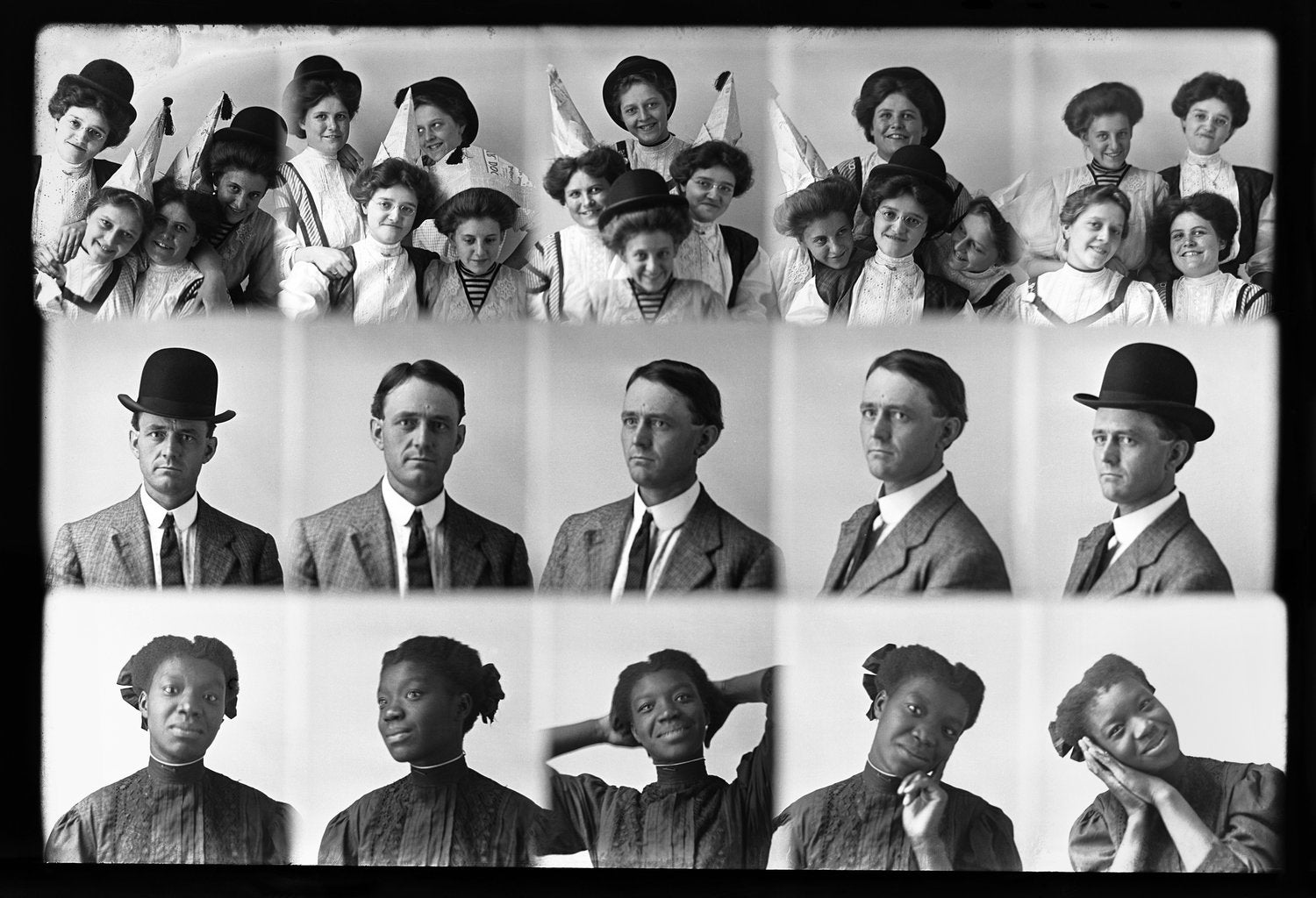

The first time I looked at Mangum’s photographs was in the fall of 2010, eight years before I would curate a book about his unique archive. I noticed the smiles and laughter, unusual in early 1900s portraiture, first. There are quirky gestures — hands behind the head, a single finger hooked over a lip, two hands intertwined. The playful portraits are the distinct difference between Mangum and other photographers of his time.

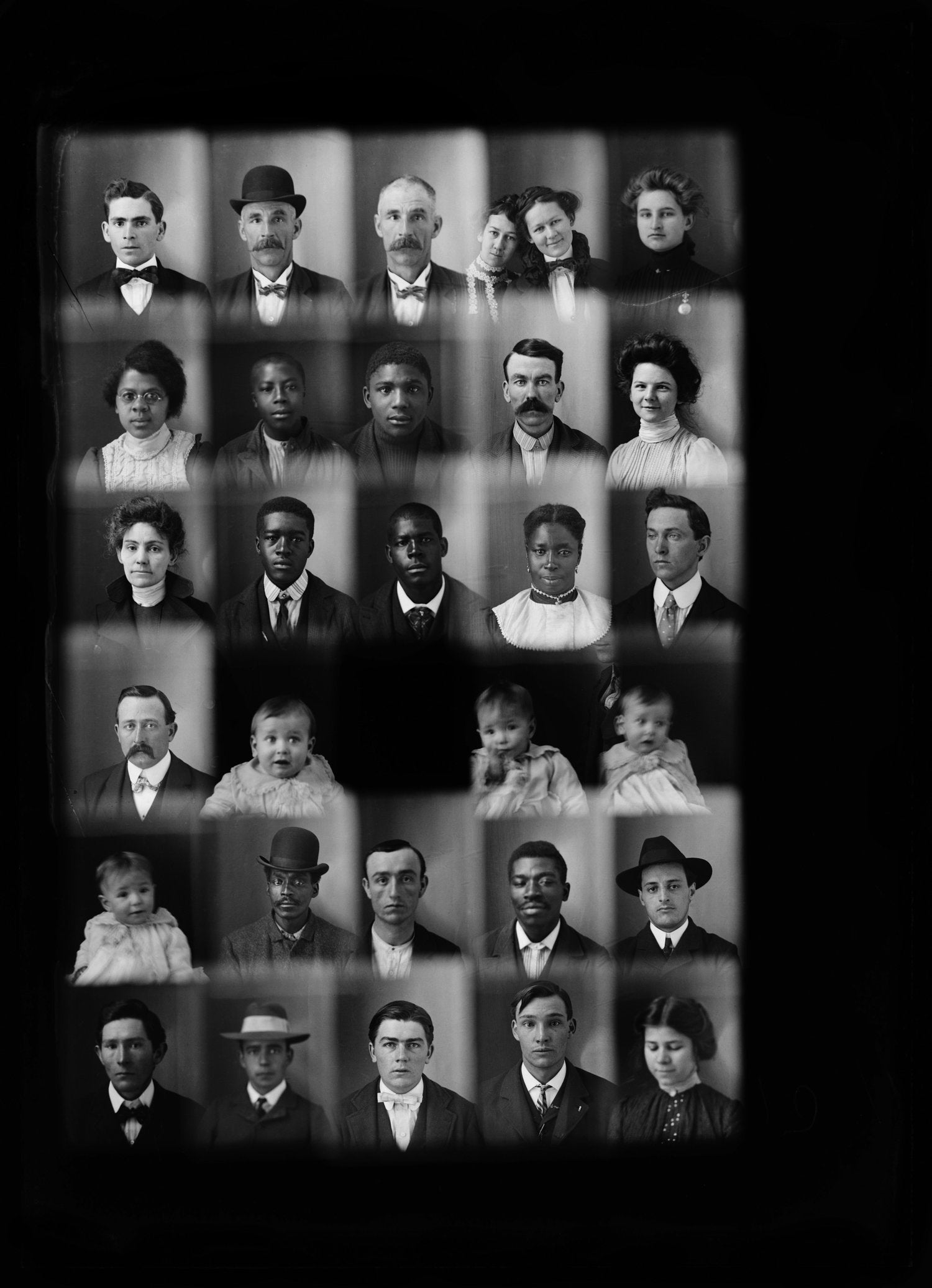

Mangum, I learned, often used a Penny Picture Camera that was designed to allow multiple and distinct exposures on a single glass plate negative. This was ideal for creating inexpensive novelty pictures because it meant multiple subjects could be photographed on a single negative. The order of the images on a single glass plate mirrored the order Mangum’s diverse clientele rotated through the studio. Thus, the negatives reasonably represent a day’s work for this gregarious photographer.

Durham, North Carolina, where Mangum began his career, was known to have an unusually prosperous black community. Black-owned businesses and organizations included furniture, cigar and tobacco factories, textile and lumber mills, brickyards, churches, barbershops, schools, a library and a hospital.

The vibrancy of black communities building new identities and creating futures in Durham and elsewhere is not lost on Mangum’s negatives. His black clients present themselves as lighthearted, resolute and everything in between. They bring their children to the studio to be photographed, an ode to the hope they have for the lives their sons and daughters will live. Though we don’t know the identity of most of Mangum’s sitters, it’s probable many of the black men and women pictured were working publicly and privately to establish black agency, independence and community vitality.

The way the artist’s diverse sitters share space is surprising. The laws and customs of Jim Crow were thriving — and black people were resisting — when Mangum was working. Yet his work shows each client to be as valuable as the next, no story less significant.

Mangum’s glass plate negatives tell a nuanced account of this history, one that affords more agency to people of color than the average textbook. One example of this disruption is the photographic evidence that Mangum did not discriminate in the way he had his sitters pose for the camera. These poses can be seen across all clients, each experiencing a typical session with Mangum.

On several occasions the elbow, hand or arm of one sitter floats into the frame of another, regardless of color, symbolizing shared spaces beyond the boundary of the negative. There are double exposures that photographically merge black and white sitters, and through this lawless, accidental composition that binds them forever we begin to further imagine both the common and distinct experiences of those pictured.

(Hugh Mangum/Courtesy of Hugh Mangum Photographs, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University)

There are no indications that Mangum intended his photographs to serve any political purposes, but it’s likely that many of his clients did. By the turn of the 20th century, many black Americans were well practiced at engaging the power of photography to challenge racist ideas, as well as to visually create and celebrate black identity.

When I asked his granddaughter, Martha Sumler, what impressions her grandfather’s pictures have left on her, she replied, “It makes me realize just how much he really liked people. I know it was a business for him, and he worked hard, but he had to have really enjoyed it and enjoyed meeting the people … to show the way life was back then.”

When he wasn’t working, Mangum spent time photographing his family, especially his wife, Annie, and daughter, Elizabeth. Martha now has many of these photos, which show Mangum’s affection for his family and reveal even more about his generous personality.

Many 19th-century family photo albums mirror the idea that family included a wide circle, beyond just blood relations. The earliest photo albums were not limited to the nuclear or extended family. They contained carte-de-visites — small exchangeable photographs of friends, acquaintances, visitors, celebrities, and significant social or civic events. These were reflective of image-driven social media of today.

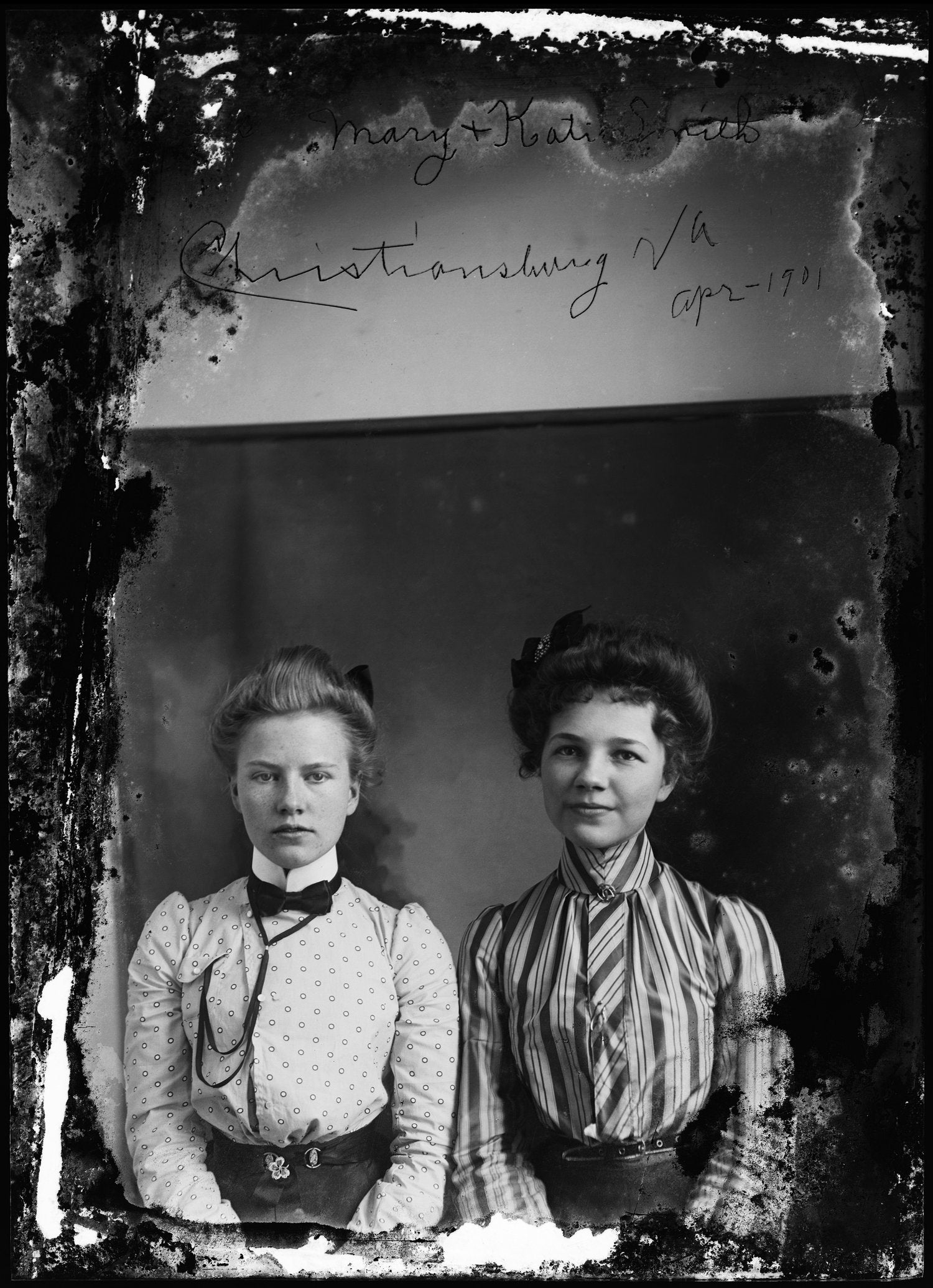

In the years I’ve spent with the photographs in the Mangum collection, it has evolved to represent a family album to me. As I sifted through the images, familiar faces gazed back at me. My affinity for some photographs has changed along with milestones in my life. When I became a mother, I looked at the women more inquisitively, wondering if they were young mothers too and how they navigated the world in their new identity. In times of heartbreak, I’m drawn to the disintegrating images. The darkness the crumbling emulsion creates –– sometimes nearly swallowing a person whole or covering them in a layer of foggy disrepair –– becomes an elegant visual metaphor for emotional pain.

(Hugh Mangum/Courtesy of Hugh Mangum Photographs, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University)

Though the American South of Mangum’s era was marked by disenfranchisement, segregation and inequality –– between black and white, men and women, rich and poor –– Mangum portrayed all of his sitters with candor, humor and spirit. Above all, he showed them as individuals, and for that, his work is mesmerizing.

Sarah Stacke is a freelance social documentary photographer and archive curator. Her book, Photos Day or Night: The Archive of Hugh Mangum, with texts by Maurice Wallace and Martha Sumler, will be released on Jan. 15, 2019 from Red Hook Editions.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))