OceanGate wants to change deep-sea tourism, but its missing sub highlights the risks

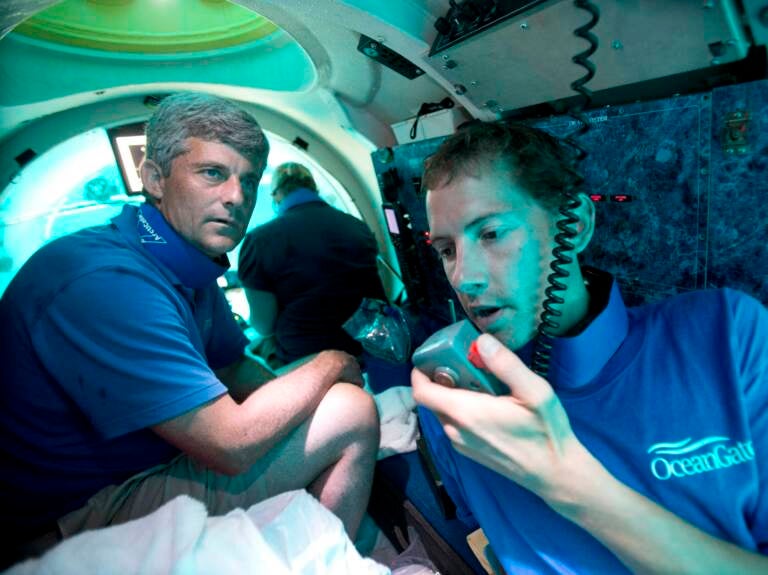

Submersible pilot Randy Holt and Stockton Rush, CEO and co-founder of OceanGate, dive in the company's Antipodes submersible off the Florida coast in 2013. Rescuers are racing to find a missing OceanGate submersible before the oxygen supply runs out for five people, including Rush, who were on a mission to document the wreckage of the Titanic. (Wilfredo Lee/AP)

In the past few years, commercial space tourism companies owned by billionaires Jeff Bezos, Richard Branson, and Elon Musk have been making headlines for sending paying customers into space.

But until this week, few people were aware of another extreme adventure industry that is just getting started: deep-ocean exploration. OceanGate, the company whose Titan submersible went missing Sunday with five people aboard somewhere near the wreck of the Titanic, is on the cutting — and potentially dangerous — edge of this new tourism.

OceanGate on its website touts its “innovative use of materials and state-of-the-art technology” and its “patented launch and recovery platform” as making the deep ocean “more accessible for human exploration than ever before.”

However, Jon Council, a submersible expert and president of the Historical Diving Society, cautions that “there are just a multitude of things that can go wrong.”

Council says that while submersible tourism has been around for decades, taking thousands of paying customers into the depths of the ocean in piloted underwater vessels, OceanGate is in a league of its own. Not only is the price tag for its Titanic expedition reportedly a whopping $250,000, no other company has attempted to take customers down nearly as far as the Titanic wreck, which lies about 13,000 feet, or 2.4 miles, under the surface.

There’s a huge difference in the pressure loads put on an ordinary tourism submersible, which might dive to a depth of around 1,500 feet vs. OceanGate’s Titan, Council says.

“All of the challenges” inherent in submersibles “are exacerbated” in a vehicle, such as Titan, built for extreme depths.

“We signed waivers that would curl your toes”

OceanGate founder and CEO Stockton Rush, who is reportedly aboard the missing submersible, studied mechanical and aerospace engineering at Princeton University. In 2019, he told the Princeton Alumni Weekly: “We don’t take tourists.”

“We like to refer to them as explorers because we go with a mission,” he said.

“The difference between an explorer and an adventurer is an explorer documents what he does, and an adventurer just goes, pounds their chest and tells their friends,” Rush said.

CBS Sunday Morning correspondent David Pogue traveled aboard the Titan submersible last year. He recalls “that when we boarded the surface vessel, we signed waivers that would curl your toes.”

“It was basically a list of eight paragraphs describing ways that you could be permanently disabled or killed,” he tells NPR’s All Things Considered. “There’s not much you can do if something goes wrong.”

OceanGate declined a request for comment.

“This is not a tourist company or an airline for the masses. This is for rich, adrenaline junkie adventurers who thrive on the risk, who have been up on [Bezos’] Blue Origin rocket, many of them,” Pogue says.

OceanGate has also offered less ambitious expeditions — and less expensive — than the dive to the Titanic, including off the West Coast, near Seattle; at the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary near San Francisco; and to the wreck of the Andrea Doria, an Italian-flagged passenger liner that sank in 1956 near Nantucket in 240 feet of water.

The Titanic sank in April 1912 after hitting an iceberg. Of the 2,240 passengers and crew on board, more than 1,500 died. It went down about 400 miles from the coast of Newfoundland, Canada, at a point in the North Atlantic Ocean where the relatively shallow American continental shelf gives way to much deeper water. Pogue says since OceanGate’s deep dives mostly occur in international waters, “there is no governing body” and therefore no regulation.

It has been compared to space tourism

Rush told the Princeton Alumni Weekly that as a child, he first dreamed of rocketing into space. “I was interested in exploration,” he said. “I thought it was space exploration. I thought it was Star Trek and 2001: A Space Odyssey and Star Wars … and then I realized, it’s all in the ocean.”

In fact, Rush has compared what OceanGate does to space tourism. He believes that deep-sea tourism could be a first step toward using submersibles for more industrial ventures, such as inspecting and maintaining underwater oil rigs, according to The New York Times. In 2017, he told Fast Company that much like Branson’s Virgin Galactic was able to parlay its credibility in space tourism into a satellite launch business, with commercial deep-sea exploration, “The long-term value is in the commercial side.”

“Adventure tourism is a way to monetize the process of proving the technology,” he said.

Meanwhile, as the search continues for the Titan, the clock is ticking — OceanGate’s website says the 22-foot submersible comes equipped with 96 hours of life support.

“As long as there’s still life support, there’s always a chance. Everyone is crossing their fingers,” Council says.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))