New data sheds light on one method to combat election lies

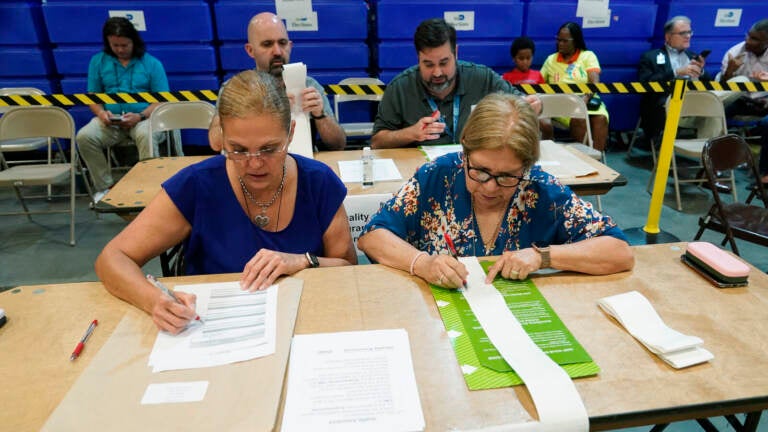

Miami-Dade County Elections Department employees check the tabulation made by voting equipment that will be used in the upcoming state primary election, Wednesday, Aug. 3, 2022, in Doral, Fla. Early voting starts Monday, Aug. 8. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

For election officials, falsehoods about America’s voting process can feel like a game of whack-a-mole.

“There’s just so much that is incorrect that they just keep repeating and repeating and repeating,” one Colorado voting official told NPR recently. “And then as soon as I have absolutely blocked off that path with actual correct information, then they just move that goal post. And they keep just moving the goal posts.”

But it’s clear this “game” has massive stakes.

A Justice Department official said in a Senate hearing this week that the federal law enforcement agency had reviewed more than a thousand hostile threats against election workers over the past year. And in a separate congressional hearing, lawmakers mulled how to make the presidential election certification process less vulnerable to partisan hijacking.

In what has essentially become an information war for the future of democracy, people driven by misinformation are acting on it to harass election workers and subvert the will of the voters. And election officials have struggled to find an effective message to fight back.

Republican Stephen Richer, the lead election official for Maricopa County, Ariz., had a speaking event cancelled last week due to a threat.

“If I said I knew [how to fight misinformation], that would be a lie,” Richer said in a recent interview with NPR. “We have ideas and we’ve been trying our hardest to employ all manner of tactics. But I don’t think anyone has cracked disinformation as a societal challenge.”

New data commissioned by the Voting Rights Lab, and shared exclusively with NPR, however, indicates a potential path forward.

The group, which advocates for expanded voter access, commissioned a series of surveys earlier this year with voters in swing states to gauge their feelings about America’s voting systems, and how different types of messages could affect those feelings.

They found that while more than a third of voters said they don’t trust the process for counting votes in the U.S., after people were shown affirmative but nonpartisan messaging about democratic systems persevering, that number significantly improved.

“The Big Lie and its proponents have so significantly eroded trust in our democracy,” said Megan Lewis, the executive director of the Voting Rights Lab. “The good news from our research is that we found that by appealing to the values that American voters hold dear — things like freedom, independence, a longing for unity — that we actually can persuade voters that the Big Lie is really nothing more than a partisan power grab.”

The organization’s research started with a control group of voters, and asked them whether they agreed or disagreed with this statement: “Overall, I trust the process for counting votes in our elections.”

Initially, 63% of voters said they did.

But when another group of voters was asked the same question after reading a statement that included things like “political candidates can challenge election results. But our system requires proof and following the law” and “let’s keep improving our elections and make them more fair, equal, and transparent” that number went up to 72% of voters.

Notably, the share of voters identified as people who already believe election misinformation improved the most after reading the affirmative messaging.

Tresa Undem, a cofounder of the public opinion research firm Perry Undem that conducted the surveys on behalf of the Voting Rights Lab, said she was stunned by the change in Republican voters after they read the positive election messaging.

“After hearing that affirmative narrative, [Republican voters] were in the double digit points more likely to say they trust the process for counting votes in elections compared to a control group,” Undem explained.

Those same voters, however, responded poorly to messaging that tried to persuade them of impending threats to democracy, including, for instance, fact-based reporting on the number of restrictive voting bills that have been introduced over the past two years in states across the country.

“People were turned off and they were like, ‘Well that’s Democratic talking points’ and that’s too negative and things aren’t that bad,” Undem said. “So what we took away from that is that … it’s much better to talk about the strength of our elections right now.”

When presented with them, political scientist Paul Gronke, of Reed College, who was not involved in the research, called the results “heartening.”

Previously, he said he worried that people who believed election misinformation were stuck in their beliefs and unswayable. There certainly still are those people he said, but it doesn’t seem to be as big a group as previously thought.

“I was not optimistic, but I read these results and it added some optimism for me,” Gronke said. “The foundation of some of these [false] beliefs seems fairly fragile.”