‘King Richard’ is a quintessential Will Smith movie, 30 years in the making

Demi Singleton and Saniyya Sidney with Will Smith in ''King Richard.'' (Chiabella James/Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.)

Like plenty of other winners before him, if Will Smith earns his first Academy Award on Sunday, it will be as much – and probably more so – for his collective body of work over the years as it is for his turn in King Richard alone. Certainly, the role is an Oscar bingo card, as Smith is playing a real person (Richard Williams, ambitious father and coach of tennis stars Venus and Serena) with a conspicuous actor-ly challenge thrown in (Williams’ southern drawl). And in case anyone doubts Smith’s commitment to The Craft, he was more than willing to don prosthetics to fully “transform” into the role, before the idea was mercifully scrapped.

But the King Richard role is also kismet, a culmination of all the performances, on-screen and off-, that led to this point. By now Smith is a vet who’s evolved right before our eyes over the course of three-plus decades. He didn’t enter into the public eye fully formed as an actor; quite the opposite, really. When he began shooting Season 1 of The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air in 1990, he was a famous 21-year-old rapper with zero acting experience to his name. He was so green that in those first few episodes, you can see him mouthing the lines of the other actors in his scenes. (His nerves as a newbie led him to memorize the entire script, he’d later admit.)

Eventually, he’d prove himself as an action star (a persona he assumed and commanded, easily) and then, a Serious Dramatic Actor, for better and for worse. And while Smith may no longer be the consistent, undisputed box office champ he once was, his trajectory is the kind audiences and awards voters like to root for.

The character Richard Williams isn’t a significant departure for the actor; it’s drawing from many elements that make up a quintessential Will Smith performance tonally, but also – and this is crucial – thematically.

What makes for a quintessential Will Smith performance, exactly?

The Fresh Prince

Key components: oft-exaggerated affectations, sound effects (“Woo!” “Psshhhh!”)

Our introduction to Will Smith the Actor also serves as the foundation for nearly every Will Smith performance, silly or serious. On The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Will is a confident, swaggering jokester who rides through life on charisma. He’s a people-pleaser, the kind of goofball who believes almost any awkward or distressing moment can be made less so by undercutting it with some levity. (See, for instance, the Very Special Episode where Will gets shot by a mugger. The – albeit, macabre – jokes continue to fly even as he’s laid up in the hospital.)

His effortless charm makes him a magnet for most people within his orbit, whether it’s the ladies, his younger cousin Ashley and her friends, his Aunt Viv (usually), or the other kids at his tony prep school. And yet, anyone as boisterous as him is bound to run up against some resistance against others who tend to be wound up a bit more tightly – namely, Carlton and Uncle Phil. (His persistence in cracking wise at their expense doesn’t help, either.) No matter, though. He is the sun, and everyone else revolves around him, no matter how begrudgingly.

Within Smith’s oeuvre, the Fresh Prince mode dominates in other roles like Oscar the fish in the animated film Shark Tale and the 1993 movie Made in America. The latter is a secondary part (Whoopi Goldberg and Ted Danson get top billing) playing Tea Cake, the childhood friend and wannabe love interest of Nia Long’s Zora. Zora discovers her mom, played by Goldberg, had her via a sperm donor – but in the few scenes Tea Cake is in, the broad humor is on full display.

(A prolonged sequence involves Tea Cake accompanying Zora to a sperm bank, where he distracts the receptionist by pretending to make a donation of his own so Zora can sneak off to find records on her birth father. Tea Cake freaks out at the prospect of having to “perform,” and Smith milks several minutes of exaggerated physical comedy and facial expressions, and yes, noises and ad libs, in this set piece.)

See also Hitch, Aladdin, and Six Degrees of Separation, all variations on The Fresh Prince, albeit in different genres and tones. The common denominator among them is the dominant mode Smith is working with here: charm.

Will, Action Hero

Key components: cocky catchphrases, intense squinting, being a cop (or some other type of law enforcement)

There are some who will say the moment Smith became a true movie star was in Independence Day, when he casually punches out that alien and delivers the assured line “Welcome to earth!”

But really, the instance when it crystallized was a year earlier, in Bad Boys. It was that classic chase scene set-piece, where the camera keeps cutting to Smith’s Detective Lowrey running in slow-mo through the Miami streets, gun in hand, and shirt fully unbuttoned and billowing in the wind to reveal his muscular bod. Up to that point, Smith’s sex appeal had primarily been wrapped up in making us laugh; here, he’s smoldering.

That chase scene leaves Smith alone, without the aid of verbal quips, and emphasizes what had always been true: At his core, he’s a physical performer. In Fresh Prince mode, his tall and lanky (or toned, depending on the role) frame can sometimes be loosey-goosey or jumbly, almost Jim Carrey-ish.

In Action Hero mode, he remains lithe but also more grounded – like a force to be reckoned with as he runs, jumps, dangles from buildings, spars with adversaries … you know, all the things required of a Keanu Reeves or Tom Cruise. (Not coincidentally, Smith has said he modeled his movie career, in part, off of Cruise.)

When the script strikes just the right amount of Action Hero notes, Smith is at the peak of his powers. In Independence Day and Bad Boys he’s Action Hero-forward, with a hint of his snarky Fresh Prince self, a potent combination. For the lighthearted Men In Black, the divide is more evenly split, with Smith serving as comedic foil to Tommy Lee Jones’s character while both battle aliens. It falters when the tone veers too sharply into Action Hero mode, with little-to-no levity to be had (I, Robot; Gemini Man), or when the movie is as terrible and bloated as Wild, Wild West.

He Is Legend

Key components: an accent, strength in the face of adversity

Other than that one time he showed up in a bizarre cameo as “Judge/Lucifer” in a movie nobody saw, Will Smith, as a general rule, doesn’t play “bad” guys or villains. When he began setting his sights on taking Serious Actor roles – i.e., your biopics and tearjerkers, the kind of stuff that gets nominated for grown-up awards rather than MTV Movie Awards – he chose the dignified, inspirational route. (In the case of the appallingly retrograde The Legend of Bagger Vance, where he plays a Magical Negro who coaches Matt Damon’s character in golf and life during the Great Depression, some have argued he started down this particular path a little too dignified.)

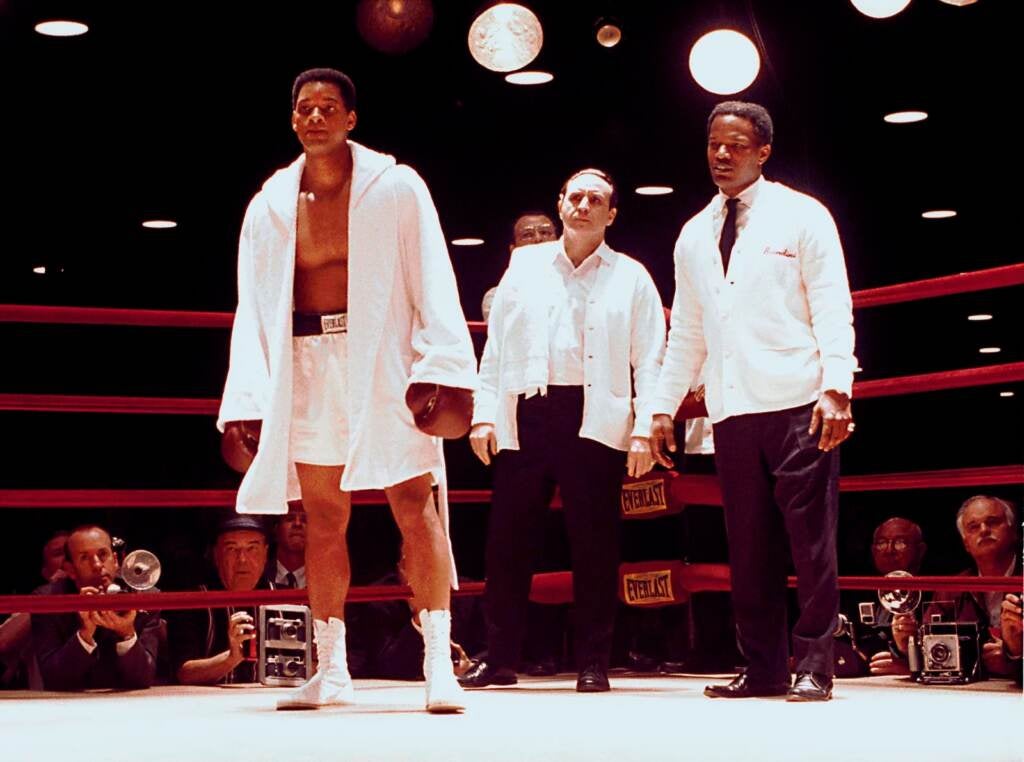

Smith’s roles aren’t just about dignity, however – they’re about being bigger-than-life, or doing extraordinary things, overcoming extraordinary odds. To kick off his Legend mode, he stepped into the role of Muhammad Ali in Michael Mann’s 2001 film Ali. Again, his physicality is front and center here, only this time the transformation is even more dramatic; baked into the narrative surrounding the film during its promotional and awards season circuit is how the actor “beefed up” to Ali’s typical fighting weight of 215 pounds and trained with a former boxer for months.

Even if it’s an obvious Oscar bait-y role (and it paid off, earning him his first nomination), the performance works so well because Ali and Smith’s essential personality traits weren’t all that different at their core. Smith dials up his own supreme confidence and magnetism to evoke Ali’s spirit, and while he never fully disappears into the role, the real-life boxer shines through clearly.

Other Legend roles have been executed to varying degrees of success: He’s effective in The Pursuit of Happyness as the real-life Chris Gardner, a man who went from a period of homelessness to becoming a CEO and motivational speaker (though the movie itself fails to wrestle with the realities of systemic inequality) and less so in Concussion, where he plays Dr. Bennet Omalu, a researcher on chronic traumatic encephalopathy in football players. (That attempt at a Nigerian accent is … something.)

Gettin’ Silly Wit It

Key components: an abundance of Oprah-like platitudes, a savior complex

At some point, Smith’s penchant for playing legends and action heroes tilted from self-confidence into self-seriousness, which in turn made some of his movie choices increasingly sillier.

That point was first hinted at in his role as Dr. Robert Neville in the apocalyptic I Am Legend, a movie he’s quite good in, because for all its doom and gloom, it contains a little bit of everything: Action Hero, Legend, and a pinch of Fresh Prince in a couple of scenes.

But the movie also has a sanctimonious Jesus-y ending – he finds a cure for a catastrophic virus and sacrifices himself for the sake of humanity – that portended a number of grating movie projects to come.

Seven Pounds was one of those mid-budget Hollywood dramas that attempts to manipulate its audience into tears and is absolutely convinced of its own profundity despite containing only the most generic of Big Ideas about life. In it, Smith embodies a sort of somber Willy Wonka character whose M.O. is to slip into the lives of strangers and determine whether or not they are worthy of receiving his assistance with whatever personal issue they’re facing. (Here, too, he ultimately becomes a martyr in an ending even more ludicrous than I Am Legend; it involves a bathtub and deadly jellyfish.)

After Earth is a movie with its roots in nepotism, a blatant attempt to make his son Jaden Smith the star of his own sci-fi thriller. One of Smith’s main assets, his physicality, is shockingly diluted here: His character is sidelined – and flatlined, performance-wise – by spending the majority of the film trapped in a crash-landed spaceship with broken legs, directing his son via voiceover on a mission to save both their lives.

When in Gettin’ Silly mode (see also: his role as a grieving dad in the treacly Collateral Beauty), Big Will tests the audience’s good will. The charm has been sapped from these performances, replaced by moroseness and overtly moralistic tones.

King Richard: A comeback

King Richard comes at just the right time for Smith. He’s been on a sort of retrospective-rejuvenation tour these last couple of years, transferring his amiable and goofy nature to social media, publishing a memoir, and revisiting those Fresh Prince years as a way of reminding everyone of why the world fell in love with him in the first place.

The character of Richard Williams finds him in the full-on Legend mode that’s gotten him awards season recognition in the past, without leaning too hard on Gettin’ Silly. His accent is a little less distracting than it was in Concussion, and it’s intriguing to watch him play a prickly personality for a change, though he isn’t quite able to make the performance rise above the script’s hagiography. (In one scene that could’ve been the starting point for the whole movie, Aunjanue Ellis, playing Richard Williams’ wife Oracene Price, has to do all of the expository heavy lifting by herself.) Is it a career-best performance? Hardly.

But as part of a larger comeback narrative that hopefully sees him moving away from self-seriousness and back to where he shines best, it works. And who doesn’t love a comeback narrative?

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))