In newly found audio, a forgotten Civil Rights leader says coming out ‘was an absolute necessity’

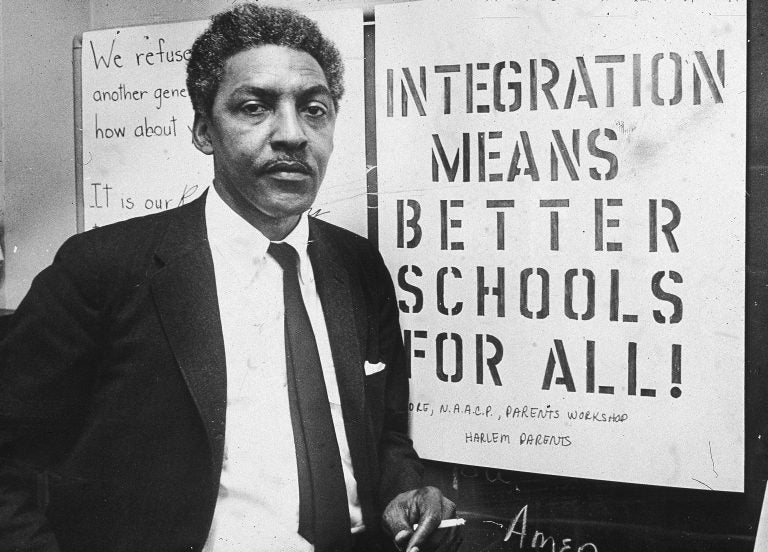

American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin, pictured in 1964, as spokesman for the Citywide Committee for Integration, at the organization's headquarters, Silcam Presbyterian Church in New York City. (Patrick A. Burns/New York Times Co./Getty Images)

He was an adviser to Martin Luther King Jr. and the organizer behind the 1963 March on Washington.

Still, Bayard Rustin’s legacy as a leading figure in the civil rights movement is little known today, even among many history buffs and within the LGBTQ community. His homosexuality cost him that visibility and was considered by some as a hindrance to the movement’s success.

Rustin died in 1987, but his silenced voice was recently resurrected in previously unaired audio from an interview with the Washington Blade in the mid-1980s. The audio will air this week in an episode of the podcast Making Gay History. It was discovered by Sara Burningham, the podcast’s executive producer.

Rustin was the target of homophobic attacks, and as he discusses in the interview, he was sidelined by other black leaders at key moments during a movement he helped steer.

“At a given point, there was so much pressure on Dr. King about my being gay and particularly because I would not deny it, that he set up a committee to explore whether it would be dangerous for me to continue working with him,” Rustin says to the Blade in the interview.

He conceded, but as Eric Marcus, the host of Making Gay History, tells NPR’s Michel Martin, Rustin kept working for the cause. In the face of constant setbacks and discrimination, Marcus says, Rustin’s commitment prevailed, a quality Marcus attributes to his Quaker upbringing.

The rare tape was provided by Rustin’s surviving partner, Walter Naegle, who preserved a library of backup recordings. Those recordings have helped foster a better understanding of the gay icon — one that Marcus concedes was absent from his civil rights education.

“I feel like I was robbed of my history as a gay person,” Marcus says. “Growing up, if I’d known known about someone like him, it would’ve been transformative.”

Marcus finds it inspiring that Rustin was open about his sexuality at a time when being gay was still considered dangerous. His arrest record included protesting and charges related to his homosexuality.

“Even though he had an arrest record because he was caught in the backseat of a car with two men in 1953 in California and then jailed for two months, he still managed to be a key figure in the black civil rights movement and organized the march on Washington,” Marcus says.

Despite the risks, Rustin felt it was his responsibility to be open about his sexuality. He traces that duty back to an experience he had as a black man in the 1940s Jim Crow South, when he took his place at the back of a segregated bus.

“As I was going by the second seat to go to the rear, a white child reached out for the ring necktie I was wearing and pulled it,” he recalled in the newly released audio. “Whereupon its mother said, ‘Don’t touch a n*****.’ ”

As Rustin tells it, here’s what ran through his mind in that moment after the white woman called him the slur: “If I go and sit quietly at the back of that bus now, that child, who was so innocent of race relations that it was going to play with me, will have seen so many blacks go in the back and sit down quietly that it’s going to end up saying, ‘They like it back there, I’ve never seen anybody protest against it.’ ”

Instead, he saw this moment as an opportunity, and an obligation, to disrupt what he saw as the inheritance of a prejudiced education in practice.

“I owe it to that child,” he told himself, “that it should be educated to know that blacks do not want to sit in the back, and therefore I should get arrested, letting all these white people in the bus know that I do not accept that.”

To Rustin, asserting his identity as an African-American went hand-in-hand with identifying as a gay man. “It occurred to me shortly after that that it was an absolute necessity for me to declare homosexuality, because if I didn’t I was a part of the prejudice,” he said. “I was aiding and abetting the prejudice that was a part of the effort to destroy me.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))