Government’s own experts found ‘barbaric’ and ‘negligent’ conditions in ICE detention

In this Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2019, photo shows detainees waiting to be processed at the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in Adelanto, Calif. The facility is a privately operated immigration detention center run by the GEO Group, which can house up to about 1900 total immigrant detainees, both male and female. (AP Photo/Chris Carlson)

In Michigan, a man in the custody of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was sent into a jail’s general population unit with an open wound from surgery, no bandages and no follow-up medical appointment scheduled, even though he still had surgical drains in place.

A federal inspector found: “The detainee never received even the most basic care for his wound.”

In Georgia, a nurse ignored an ICE detainee who urgently asked for an inhaler to treat his asthma. Even though he was never examined by the medical staff, the nurse put a note in the medical record that “he was seen in sick call.”

“The documentation by the nurse bordered on falsification and the failure to see a patient urgently requesting medical attention regarding treatment with an inhaler was negligent.”

And in Pennsylvania, a group of correctional officers strapped a mentally ill male ICE detainee into a restraint chair and gave the lone female officer a pair of scissors to cut off his clothes for a strip search.

“There is no justifiable correctional reason that required the detainee who had a mental health condition to have his clothes cut off by a female officer while he was compliant in a restraint chair. This is a barbaric practice and clearly violates … basic principles of humanity.”

These findings are all part of a trove of more than 1,600 pages of previously secret inspection reports written by experts hired by the Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties. In examining more than two dozen facilities across 16 states from 2017 to 2019, these expert inspectors found “negligent” medical care (including mental health care), “unsafe and filthy” conditions, racist abuse of detainees, inappropriate pepper-spraying of mentally ill detainees and other problems that, in some cases, contributed to detainee deaths.

These reports almost never become public.

For more than three years, the federal government — under both the Trump and Biden administrations — fought NPR’s efforts to obtain those records. That opposition continued despite a Biden campaign promise to “demand transparency in and independent oversight over ICE.”

The records were obtained in response to a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit brought by NPR. After two years, a federal judge found that the government had violated the nation’s public records law and ordered the release of the documents.

The reports provide an unprecedented look at the ICE detention system through the eyes of experts hired to investigate complaints of civil rights abuses, who provide an often unvarnished perspective. These experts have specific expertise in subjects such as medicine, mental health, use of force and environmental health. Sources familiar with these inspections tell NPR that they often uncover problems that other government inspectors miss.

“These reports are chilling. They are damning,” said Eunice Cho, senior staff attorney at the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project and an expert on ICE detention, when NPR shared the reports’ findings. “They really show how the government’s own inspectors can see the abuses and the level of abuses that are happening in ICE detention.”

The reports obtained by NPR depict a wide spectrum of problems in ICE detention.

Most immigration detention facilities are managed by private, for-profit corporations that contract with the government, including GEO Group and CoreCivic. Local jails, typically operated by county sheriff’s departments, also enter into contracts with the government to hold detainees on behalf of ICE.

Legally, immigration detention is considered civil — not criminal — in nature. “Detention is non-punitive,” ICE states on its website. Immigration detention is primarily for holding people who are awaiting the adjudication of their immigration cases. That can include immigrants apprehended at the border who are seeking asylum; people who entered the U.S. illegally and whom the government wants to deport or deems a public safety risk; and permanent residents who are hit with deportation orders.

The main goal of ICE detention is to make sure immigrants show up for their court dates. But the conditions revealed in the inspection reports often appear indistinguishable from prison.

The inspectors found what they described as racist harassment of immigrants and retaliation against detainees who filed complaints.

“Examples of mistreatment include a Sergeant entering the female unit and greeting the female detainees by yelling, ‘Hello a**holes and bitches,'” an inspector found at the Orange County Jail in Goshen, New York. “Multiple staff make comments such as, if detainees do not like the treatment, they should not have come to our country. A [correctional officer] working in a male unit confronted a group of detainees stating, ‘Who’s the f***ing p**** who made the complaint against me?'”

The Orange County Sheriff’s Office did not answer NPR’s questions for this story.

At the Houston Contract Detention Facility, which is operated by CoreCivic, detainees alleged “harassment by custody staff, discrimination of detainees by facility staff based on race, and retaliation by facility staff,” but the inspector found that the facility did not investigate the complaints.

“These now outdated reports are from 4-6 years ago and are not reflective of current facility operations,” said Ryan Gustin, CoreCivic’s director of public affairs, in a statement. “CoreCivic policy prohibits harassment and discrimination on the basis of race, gender, age or any other protected classification in accordance with applicable laws and regulations. Our staff are trained and held to the highest ethical standards.”

Inspectors also found incidents of unjustified use of force by detention staff.

At the Calhoun County Correctional Facility in Battle Creek, Mich., an inspector found that the jail staff was locking mentally ill detainees in restraint chairs without justification and using pepper spray when it was not warranted.

“The use of chemical agents or Use of Force with mentally ill detainees, who because of their mental illness are unable to conform their behavior, has been opined as a violation of constitutional rights in Florida and California,” the inspector wrote.

The Calhoun County Sheriff’s Office referred NPR’s questions about this report to ICE.

The most consistent — and sometimes deadly — problems relate to medical and mental health care.

Experts told NPR that prisons and jails often fail to provide adequate care to people who are locked up. ICE detention, they say, is even more problematic because detainees are frequently transferred between facilities, which increases the odds that medical records and care plans fail to move with people, and because the facilities are often located in remote areas that lack access to high-quality health care.

In one instance cited in the reports, a pregnant woman held at the El Paso Service Processing Center slipped and fell in the shower. “As a best practice, a pregnant female with abdominal pain must have an ultrasound to rule out an ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy outside of the uterus) as this is a life threatening condition,” the inspector who examined the medical records wrote. But the medical staff did not perform an ultrasound, and as a result, “the medical care did not meet the standard of care of a pain in pregnancy,” the inspector wrote.

The medical experts sometimes criticized a lack of adequate staffing for ICE medical clinics, including physicians who did not regularly work on-site.

An inspector who investigated conditions for ICE detainees at the St. Clair County Jail in Port Huron, Mich., described a phone call with the facility’s new medical director.

“During our conversation I learned that this position is new for him and he is not yet well integrated into the medical care at the jail,” the inspector wrote. “When asked if he was ‘in charge of the medical care at the jail,’ [the medical director] responded ‘I guess so’.”

The inspector concluded that “it is unclear whether he is providing the oversight needed to ensure adequate medical care and treatment of ICE detainees at the facility.”

The St. Clair County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to NPR’s request for comment.

Detention and the bitter debate over immigration policy

The ICE detention system has become a major point of contention in the bitter political debate over U.S. immigration policy. The Biden administration says it has increasingly relied on alternatives to detention, like GPS monitoring, and has prioritized detention in cases where there are threats to public safety and national security. A majority of people in ICE detention have no criminal record, according to government data compiled by Syracuse University’s Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse.

Critics of the Biden administration’s border policies, including many Republicans in Congress and presidential candidates, have proposed tougher policies that would likely send tens of thousands more people into ICE custody.

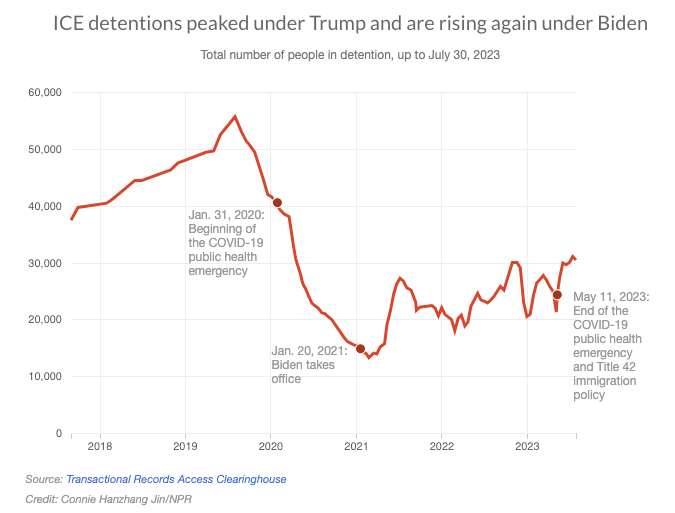

Advocates and lawyers for immigrants, meanwhile, have criticized the Biden administration for breaking a campaign promise to “end” the use of for-profit detention centers and for roughly doubling the number of people in ICE detention since President Biden’s inauguration.

In one instance, a prison that closed following a Biden administration order to phase out privately run Federal Bureau of Prisons facilities was essentially converted into a privately run ICE detention center. ICE is also fighting New Jersey’s effort to close a for-profit detention center in the state — an ICE official said in a court filing that closing the facility would be “catastrophic.”

The Biden administration has stopped using a handful of sites as detention centers due to concerns about poor conditions, while some other facilities have voluntarily ended their contracts with ICE. The inspection reports document several findings of inhumane treatment at some of the facilities that ICE no longer contracts with.

An inspection report obtained by NPR found filthy conditions at Alabama’s Etowah County Detention Center, including communal nail clippers with “blood on the blades,” medical exam rooms with no hand-washing sink and living conditions that were “unsanitary” and “unsafe for occupancy.” In March 2022, ICE announced that it would stop working with the facility because it “has a long history of serious deficiencies identified during facility inspections and is of limited operational significance to the agency.”

Separately, the York County Prison in York, Pa., stopped working with ICE in July 2021 in a dispute over the cost of incarcerating ICE detainees. The 2019 inspection of the facility revealed some of the most serious violations of ICE detention standards in the eyes of the government’s inspectors.

“Female detainees reported staff would verbally threaten them with being locked up in the segregation unit and ‘going to the hole’ for behaviors that did not violate the rules and did not warrant isolation,” the inspector wrote. “Female detainees also reported that staff would tell them they cannot cry and are quick to put them on suicide watch just for crying.”

A majority of the records NPR obtained relate to facilities that remain active.

Internal government watchdogs have found that ICE detention facilities frequently fail to meet their own standards and that inspections have not led to systemic improvements. The ACLU’s Cho says the problems identified in the reports that NPR obtained have largely persisted, an assessment echoed by immigration attorneys across the U.S., as well as sources familiar with the inspection process.

“If anything, conditions have probably gotten worse,” Cho says, noting widespread reports of poor treatment and increased use of solitary confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic. In several instances, the reports obtained by NPR warned ICE officials that overcrowding and poor cleaning practices were contributing to the risk of contracting infectious diseases.

“ICE wants to keep as many of these facilities open and running,” Cho says, “so there’s often a blind eye turned to what’s happening and the abuses people are actually facing.”

Over the course of several weeks, NPR requested interviews with representatives of the Biden White House and ICE. Neither was willing to make any officials available.

“ICE takes its commitment to promoting safe, secure, humane environments for those in our custody very seriously,” a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson said in a statement, noting that the agency had scaled back or closed multiple ICE detention facilities. “The agency continuously reviews and enhances civil detention operations to ensure noncitizens are treated humanely, protected from harm, provided appropriate medical and mental health care, and receive the rights and protections to which they are entitled.”

In a statement, a White House spokesperson said, “These reports concern conditions in the prior Administration.” The statement did not contend that conditions have since improved.

“President Biden continues to support moving away from the use of private detention facilities in the immigration detention system,” the statement went on, noting the Biden administration’s greater use of alternatives to detention. “We could be making a lot more progress if Congress would give us the necessary funds and reforms that we’ve been asking for since day one.”

Donald Trump’s presidential campaign did not respond to NPR’s request for comment.

“At every step of the way, my dad was failed”

Out of all the incidents cited in the more than 1,600 pages of inspection reports NPR obtained, the death of Kamyar Samimi stands out. NPR examined other public records and legal filings about the case and interviewed Samimi’s daughter regarding what an inspector called an “astonishing” series of failures.

In November 2017, Neda Samimi-Gomez wanted to invite her father to Thanksgiving, as she did every year.

But Kamyar Samimi wasn’t picking up the phone.

Growing up, Neda remembers spending time in the garage watching her dad at work as an auto mechanic, a can of Pepsi in his hand, and sitting down together to watch NASCAR, George Lopez, and Law & Order. “That was our thing. Like, he wanted me to become a lawyer because of Law & Order,” she says.

Kamyar Samimi was born in Iran and came to the U.S. in the 1970s, becoming a lawful permanent resident.

“He loved it here,” Neda says.

He also sometimes struggled with drugs.

His daughter says it started when he was a kid back in Iran and was given opium for tooth pain.

In the U.S., he was prescribed methadone, which he took to manage opioid use disorder for more than two decades.

By 2017, Neda was in her 20s, Kamyar was 64 years old — and even though they both lived in the Denver area, she says, they saw each other only “from time to time.”

Thanksgiving came and went without hearing from her dad.

Neda and her family were unaware that on Thanksgiving Day 2017, Kamyar was being held in an ICE detention center in Aurora, Colo., a facility run by GEO Group.

Kamyar Samimi was a lawful permanent resident. But back in 2005, he pleaded guilty to possession of cocaine — less than a gram in total — and was sentenced to community service.

Twelve years later, ICE decided that this conviction rendered him deportable. Federal law allows the government to revoke an immigrant’s lawful permanent resident status and deport them for a variety of reasons, including for committing crimes of “moral turpitude” or committing an “aggravated felony.”

Kamyar’s family was worried when they learned about his situation after Thanksgiving, Neda says, but they thought it was just a paperwork issue.

Then two weeks after Kamyar’s arrest, an ICE officer dropped off a business card at Neda’s work and said to call.

“The officer picked up the phone and said, ‘We don’t know if anyone’s been in touch with you, but we wanted to let you know that your father passed away over the weekend,'” Neda recalls.

Neda and her family worked with the ACLU to gather information about Kamyar’s death and ultimately filed a lawsuit against GEO Group.

They discovered a detainee death review conducted by ICE showing that the staff at the Aurora ICE Processing Center had cut Kamyar Samimi off his medication cold turkey. Nurses relied on withdrawal guidelines for alcohol instead of opioids and thought Samimi was “faking” his withdrawal symptoms, including a seizure.

The facility’s doctor never examined Samimi.

After a sleepless night when he screamed in his cell that he couldn’t breathe, Samimi’s condition worsened and he vomited blood clots. A nurse said, “He’s dying.” But the staff delayed several more hours before calling 911.

On Dec. 2, 2017, only two weeks after being arrested by ICE, Kamyar Samimi was pronounced dead.

The medical expert inspecting the Aurora ICE Processing Center for the Department of Homeland Security looked into the case and appeared to be stunned.

“The complete lack of medical leadership, supervision and care that this detainee was exposed to is simply astonishing and stands out as one of the most egregious failures to provide optimal care in my experience,” the medical expert wrote.

“The magnitude of failures to care for this detainee is only surpassed by the number of such failures. It truly appears that this system failed at every aspect of care possible,” the inspector went on.

That finding had previously been referenced in a congressional staff report. Neda Samimi-Gomez said she had never seen it before.

“It says it right here,” Samimi-Gomez says of the report. “At every step of the way, my dad was failed.”

Samimi-Gomez and her family sued GEO Group. The lawsuit resulted in a confidential settlement in which GEO Group did not admit wrongdoing.

She said she never received an apology from ICE, and she is still left with flashbacks from the moment she broke the news of her dad’s death to her mom.

“I can still hear my mom’s scream on the phone when I told her,” she says. “It’s just always under my skin.”

Another death in Aurora

In addition to the Samimi case, the expert who inspected the Aurora ICE Processing Center identified other examples of negligent medical care, including a detainee who was found to have contracted HIV but was never told of the diagnosis and a detainee who had persistent blood in their urine “without a proper investigation” into its cause.

The inspector wrote that if these problems were found in a hospital, it could be forced to shut down.

“Any of these findings alone can be considered an ‘Immediate Jeopardy’ according to the Center[s] for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and can lead to the closure of large health systems,” the inspector wrote.

The facility did not close, and it currently holds about 700 immigrant detainees. Lawyers who have clients at the Aurora ICE Processing Center say they have not seen an improvement in the medical care since that report and have continued to file complaints about the conditions there.

A recent detainee death at the Aurora facility sparked renewed protests and calls for the detention center to close.

On Oct. 13, 2022, the staff at the Aurora ICE Processing Center, once again, called 911 to report a medical emergency.

NPR obtained a copy of the call under the Colorado Open Records Act, and the audio, which has not previously been made public, reveals a series of lapses in communication in a time-sensitive medical crisis and raises questions about the training at the facility.

First, the unnamed detention officer who called 911 gave the dispatcher the wrong address for the facility where he worked.

Then he placed the dispatcher on hold when asked how paramedics could access the building.

He did not know any of the specifics of the medical emergency, stating only that it was a “code blue.”

He also did not know the patient’s age — eventually, the detention officer stated that the patient was in his “late 20s.”

In fact, the patient, Melvin Ariel Calero-Mendoza, was 39 years old.

What the detention officer failed to communicate was that Calero-Mendoza, an immigrant from Nicaragua, had collapsed at the facility. According to a subsequent autopsy report, Colorado Public Radio reported, the cause of death was a pulmonary embolism.

Experts in emergency medical response told NPR that getting accurate information about a patient’s symptoms is key because that information can help determine how many paramedics are needed, how quickly they need to respond and what kind of medical equipment they might need. These experts also underscored the need for jails, prisons and detention centers to have a clear plan for how to get paramedics access to patients in need.

“At a minimum, a professional caller should have an address available and know where the patient is in that complex,” said Brett Patterson, an expert in emergency dispatch and chair of the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch’s Medical Council of Standards.

“In this kind of scenario, every second counts,” said Elizabeth Jordan, an attorney for Calero-Mendoza’s family.

“The depth of indifference that this caller displayed was shocking,” Jordan said, especially given the previous death of Kamyar Samimi.

“The family is disappointed and horrified by this call,” Jordan added.

In response to NPR’s request for comment for this story, GEO Group spokesperson Chris Ferreira said in a statement, “We are unable to comment on specific cases as it relates to individuals in the care of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.”

“We take our role as a service provider to the federal government with the utmost seriousness and strive to treat all those entrusted to our care with dignity and respect,” the statement went on. “As previously and publicly expressed, we offer our condolences to Mr. Calero-Mendoza and Mr. Samimi’s families and their loved ones and remain committed to ensuring the health and safety of all those in our custody and care.”

The news of another death at the Aurora ICE Processing Center under seemingly similar conditions to her father’s hit Neda Samimi-Gomez hard.

“I think more than anything, I just don’t want anyone to deal with what I’ve been dealing with for the last five years,” Samimi-Gomez said. “Nobody should have to feel this way.”

“This man could die”

In addition to examining the experts’ inspection reports, NPR also sought to corroborate their accounts by speaking to immigrants who have been locked up in these facilities.

In interviews, immigrants told NPR their experience in ICE detention had left them with physical and emotional scars.

In the late 1980s, José fled the civil war in his home of El Salvador and came to the U.S., where he found work as a handyman. He did not have legal authorization to remain in the country, and in 2022, José was arrested and sent to ICE detention at the Orange County Jail in Goshen, New York. He says his cell was filthy and smelled like urine.

José, who is now 57 years old, asked NPR not to disclose his last name because he’s concerned about facing retaliation for speaking out about conditions in ICE detention.

The inspector from the Department of Homeland Security found problems with a failure to track medical issues at the Orange County Jail. In 2017, according to the inspection report NPR obtained, the jail did not use a modern electronic medical record system. Instead, the jail relied on paper records. The Orange County Sheriff’s Office did not respond to NPR’s question about whether it still uses paper records.

Five years after that inspection report, José says those problems persisted and nearly killed him.

José, according to medical records viewed by NPR, has had heart issues going back a decade, as well as diabetes. When he arrived at the Orange County Jail, he was taking prescription medications to manage his health problems. José says that the Orange County Jail did not provide him with his medications and that his health immediately began taking a turn for the worse.

He started experiencing nausea, shortness of breath and chest pain that radiated down his left arm. He says he fainted two days after being booked into the facility.

When he came to, he overheard a guard say, “This man could die.”

José was taken to a nearby hospital, where the doctors found that he had symptoms consistent with a heart attack. The doctors performed surgery to place a stent in his coronary artery. The doctors eventually sent José back to the jail but with strict instructions to continue taking his medications, including a new set of prescriptions to take post-surgery. But again, José and his lawyers say, the jail failed to provide him with his medications for multiple days once he got back to the facility.

Ultimately, his lawyers were able to secure his release from the jail, citing the problems with medical care. José’s immigration case remains ongoing.

José says he believes his time in jail did permanent damage to his heart.

A spokesperson for the Orange County Sheriff’s Office initially said they would provide comment for this story but ultimately did not respond to NPR’s questions.

“It feels like hell on earth”

Dalila Yeend says she’s still coping with the trauma of her experience in ICE custody.

Yeend was born in Australia and was brought to the U.S. by her mother. She says she and her family worked with an immigration lawyer who assured them — apparently wrongly — that they had filed the paperwork to obtain legal status. She eventually had two kids of her own.

But when Yeend rolled through a stop sign in Troy, N.Y., in 2018, she was arrested and ultimately brought to ICE’s Buffalo Service Processing Center to face deportation charges.

“It feels like you’re in jail,” she says. “It feels like hell on earth.”

Yeend says she had struggled with mental illness for a lot of her life and has a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. At the time she was arrested, she was taking an antidepressant and an antipsychotic medication.

Now, she found herself at a facility where, according to a 2018 inspection report, mentally ill detainees were “‘falling through the cracks,’ their distress was being exacerbated, increasing their risk of suicidal behavior.”

Yeend says she was not provided with her medications when she was locked up and was not seen by a psychiatrist for close to a month.

“I just was crying and crying and crying,” she says. “My children were left alone at home and I didn’t know that they were going to be OK and I also didn’t know what was going to happen.”

Over the course of about three months locked up, Yeend says, she saw two mental health providers over Zoom, “and the Zoom calls were maybe 10 minutes, if that.” Rather than resume the medications she had been taking, Yeend says she was prescribed a sedative to make her sleep.

Eventually, Yeend was able to secure her release from the facility and reunite with her children. She has obtained legal immigration status and become an advocate for immigrant rights. She is also a plaintiff in an ongoing lawsuit against the private operator of the facility, Akima Global Services, over the system of detainee labor. ICE detainees are sometimes paid $1 a day to work as custodians or in the kitchen as part of ICE’s “voluntary work program.” A number of lawsuits have alleged that ICE detainees are essentially forced to perform work for meager wages or face retaliation. Akima Global Services did not respond to NPR’s request for comment.

Yeend says she has post-traumatic stress disorder from her time in ICE custody.

“I don’t think anyone’s mental health is their concern whatsoever,” she says. “I don’t think they care.”

The audio for this story was produced by Monika Evstatieva and edited by Barrie Hardymon. Digital production by Meg Anderson; research by Barbara Van Woerkom; copy editing by Preeti Aroon; photo editing by Emily Bogle and Grace Widyatmadja; visuals and graphics editing by Alyson Hurt and Connie Hanzhang Jin; video production by Jackie Lay. NPR’s Tirzah Christopher, Chiara Eisner, Asma Khalid and Ayda Pourasad also contributed to this story.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))