How much should the public be told about research into risky viruses?

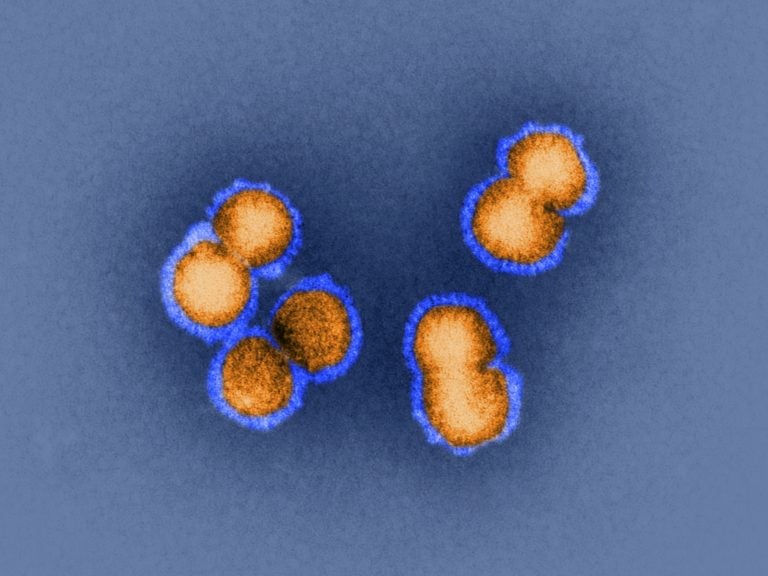

H5N1 bird flu virus is the sort of virus under discussion this week in Bethesda, Md. How animal viruses can acquire the ability to jump into humans and quickly move from person to person is exactly the question that some researchers are trying to answer by manipulating pathogens in the lab. (SPL/Dr. Klaus Boller/Science Source)

U.S. officials are weighing the benefits and risks of proposed experiments that might make a dangerous pathogen even worse — but the details of that review, and the exact nature of the experiments, aren’t being released to the public.

Later this week, officials are to hold a meeting in Bethesda, Md., to debate how much information to openly share about this kind of controversial work and how much to reveal about the reasoning behind decisions to pursue or forgo it.

The meeting comes as the high stakes of this research are coincidentally being highlighted by events in China, where public health workers are grappling with an outbreak of a new coronavirus. The virus likely first arose in animals and seems to have acquired the ability to be transmitted from person to person.

How animal viruses can acquire the ability to jump into humans and become contagious is exactly the question that some researchers are trying to answer by manipulating pathogens in the lab to explore what genetic changes alter their virulence and transmissibility.

‘Potential pandemic pathogens’

Scientists have argued for years over whether it’s ever justifiable to do experiments that might create “potential pandemic pathogens” — viruses or other germs that are likely to be highly contagious from person to person and capable of causing a significant number of illnesses and deaths.

Some think that if this research is to be done, it requires an unusual degree of transparency because it involves deliberately making a pathogen more risky.

“It seems to me that the review process should be very much weighted toward making sure that as many people as possible are satisfied that that risk is justified by some very large benefit to health and welfare of people,” says Marc Lipsitch, a professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who has been critical of past efforts to create genetically-altered bird flu viruses.

Those in favor of this virus tinkering say it’s necessary to prepare for the possibility that an animal pathogen circulating out in nature might mutate in a way that lets it start sickening humans and spreading widely. It’s not a theoretical danger; past pandemics, like the 1918 flu, killed millions.

That’s why some researchers say they have to take worrisome viruses into the lab and tweak them in order to see what these germs are capable of. The findings could tell public health workers what potential dangers lie ahead, so that they can get ready with the right surveillance tools, vaccines and medicines.

Risks of accidents — or terrorism

Other biosecurity experts, however, question how much useful knowledge would really be gained from these studies. And in their view, it just isn’t worth the possibility that a lab-created virus might get unleashed — either by accident or because someone deliberately used it as a bioweapon.

Since concerns about this type of virus research were raised back in 2011, it has been halted first by a voluntary moratorium that went on for more than a year and then by a pause put in place by the White House that lasted about three years.

In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services created a new framework for reviewing proposed experiments, which laid out criteria for what sort of studies are eligible to get funding and go forward. It requires, for example, that there’s no feasible, safer means of answering researchers’ questions about a pathogen.

“There have been two proposals that have made it through the review process and have been funded,” says Carrie Wolinetz, associate director for science policy and acting chief of staff to the director of the National Institutes of Health. “They’re both related to influenza research and the transmissibility of avian influenza. One of the things these scientists are studying is how does the flu virus jump between species because that is one of the important things that we need to understand to help us understand the evolution of the flu virus.”

A third proposal is currently under review, according to a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services.

Should the public be told ahead of time?

NPR asked for general details about this third proposal but was told the pre-funding review is not public. If the project passes the review and the NIH decides to fund it, the information can then be accessed in the general database of NIH-funded research. HHS is also planning to list projects that are funded after this special review on the website that describes the decision-making process.

Now that government has actually done a couple of these reviews, says Wolinetz, “it’s an opportunity to ask the question: ‘Are we doing this appropriately? Are we in fact being correct in our balancing of transparency and security, or any other considerations?’ ”

To get advice on how much should be disclosed, officials are turning to a panel of independent experts, the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity.

‘It’s a little bit tricky’

There’s a lot of interest out there in how these reviews get done, notes Wolinetz, but “it’s a little bit tricky, because all of these discussions are happening before funding decisions are made. Under current rules and regulations in the government, those conversations, pre-award conversations, are protected.”

That’s to ensure, for example, that someone’s idea for a novel experiment doesn’t get stolen by another researcher. It also lets reviewers be candid in their critiques. What’s more, if a proposed study was deemed too alarming to fund, it might not make sense to make that idea available to all.

On the other hand, some biosecurity experts argue that the public needs to know who is evaluating the risks and benefits and exactly what their reasoning is.

Otherwise, these experts say, it will be impossible for the public to have any trust in this oversight system.

“I just worry that there needs to be a range of voices and disciplines involved in decision-making about this work,” says Thomas Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, who notes that the government hasn’t named the people whose expertise was tapped to do the reviews.

“I think it would increase confidence of those in the community that are worried about this work to have it be transparent and have voices be heard that are outside the direct funder and scientific researcher,” says Inglesby. “More transparency would lead to a chance for more discussion about it before the work started.”

‘NIH should be transparent’

Yoshihiro Kawaoka, of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, is one of the researchers whose flu experiments got funded after undergoing this special review. Kawaoka told NPR by email that he agreed that “NIH should be transparent in announcing funding of the work, and disclosing the review process. But, that information should be balanced to ensure security measures of the work and the safety of research personnel are not compromised.”

A biosafety official at his university, Rebecca Moritz, explained that specific security requirements might need to be kept secret to protect the public. In addition, she noted that the government review “contains sensitive information because, in it, we are required to detail the ways in which the research could potentially be misused.”

The other research proposal that passed the review and got NIH funding came from Ron Fouchier, a virologist at Erasmus MC in the Netherlands. He told NPR by email that he would have no problem with the public knowing a “coarse outline” of his plans, but that he would leave all of this up to the NIH and the federal government.

“I am just a scientist caught in this process,” Fouchier said.

Beyond the question of how much information should be available about the U.S. government’s funding decisions, some continue to worry about the consequences of publicly publishing any research results that would describe how to make a pathogen more dangerous.

The HHS decision-making framework says funded research may require “risk mitigation strategies” that might include “methodologies for responsible communication of results.”

But Inglesby says that “responsible communication” has never been defined.

“If this work shows that it’s possible to make a flu virus or some other virus more dangerous, more capable of spread from person to person,” he says, “then what is the ‘responsible communication’ pathway?”

He points out that “once we publish the mechanisms for making pathogens more dangerous —potentially ‘pandemic dangerous’ — we can’t take that information back. That information will be out there online for good.”

Wolinetz told NPR that any researchers who receive funding from the NIH after going through this review would be expected to communicate whatever is learned in the normal way, through the open scientific literature.

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))