Generation unemployed: Another class of graduates face pandemic-scarred future

College senior Bao Ha has applied to more than 100 jobs. So far, he's had no luck. (Courtesy of Bao Ha)

The job market is starting to roar back, but for anxious college seniors like Bao Ha, it’s a different reality altogether.

“I’ve probably applied to like 130 or 40 jobs or something,” Ha says. “I have not gotten even an email back, or an interview.”

Ha is graduating soon from Macalaster College in Minnesota, and between his anthropology thesis and trying to check items off his senior year bucket list, he’s spent hours crafting cover letters and scouring job postings.

And now, self-doubt has started to trickle in.

“Maybe my cover letter sucks, maybe my resume sucks,” he says.

By many indications, the job market is coming back: The employment report was a blockbuster, showing more than 900,000 jobs created, with a big recovery in previously struggling sectors like restaurants.

The problem for students like Ha is that youth unemployment remains stubbornly high. Though much better than the 27.4% rate in April last year, the unemployment rate for those aged 16-24 actually ticked higher, to 11.1% in March. That was significantly above the overall unemployment rate of 6.0%.

That’s no surprise to Elise Gould, a senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute. When the economy tumbles, the job market tends to be worse for young people, she says.

The reality is that there may be plenty of cheaper-to-hire college graduates, but in an economy still recovering from major layoffs, there are also plenty more experienced workers desperate for jobs.

“They’ll choose, all else equal, people with more experience,” Gould says about employers. “So young workers are left out in the cold and many are going to have a hard time starting their career.”

Erica Schoenberg would know.

She was a member of the class of 2020, which had the misfortune of graduating in the brunt of the pandemic.

A year after Schoenberg watched her virtual graduation ceremony from Trinity University from her living room couch, she’s back at her parents’ home because she can’t find a full-time job.

Needing the income and something to occupy the day, she took a part-time job at a fabric store, and she also teaches Hebrew school over Zoom.

It’s far from the career in publishing she imagined, and Schoenberg frets about the gap on her resume that lengthens by the day.

“My mom said she thinks I can put recent graduate up until the next people do,” Schoenberg says.

The difficulties in finding that first job are magnified for young people of color, especially those without college degrees. Many worked in sectors like hospitality and retail, where millions lost their jobs.

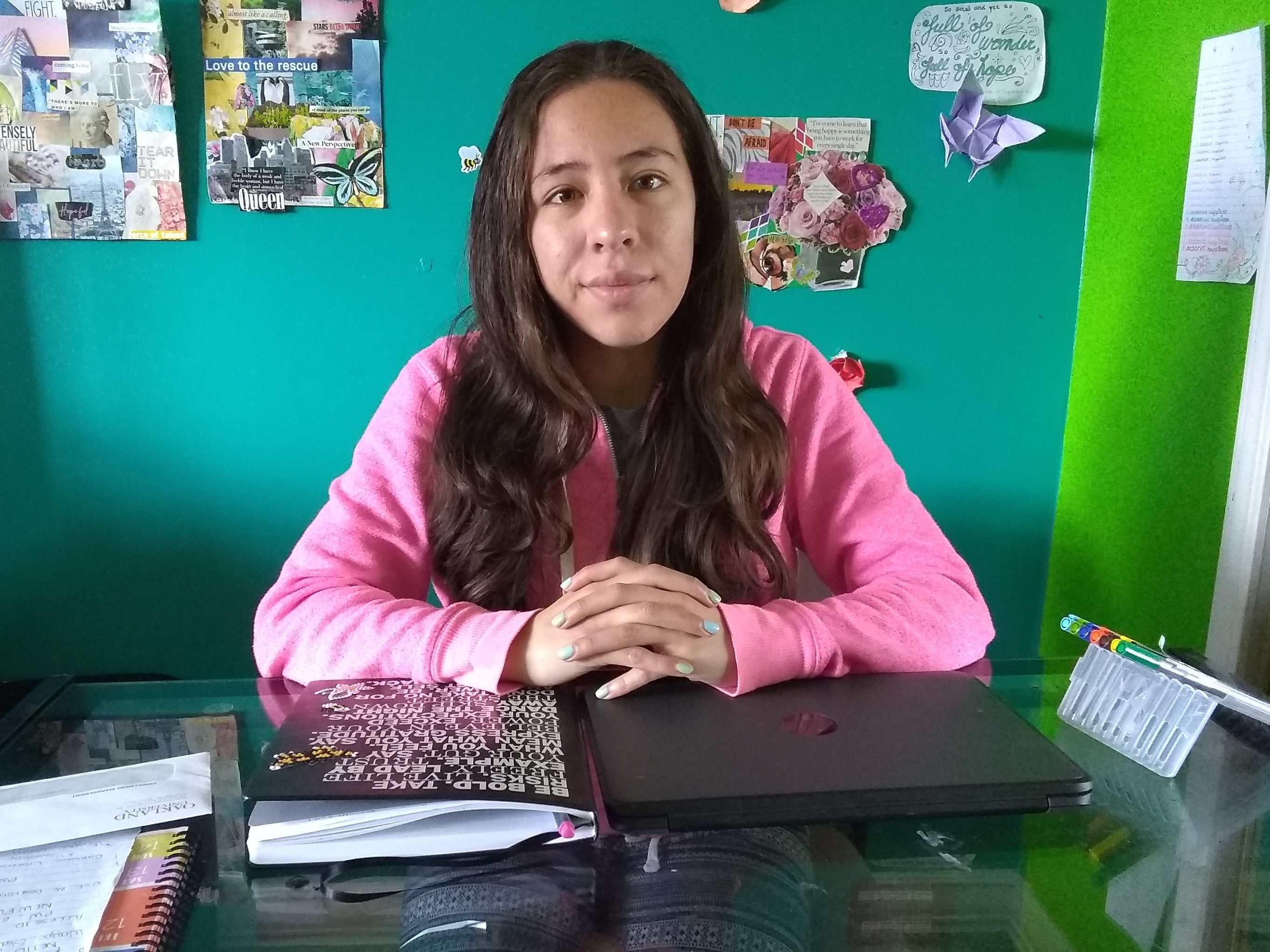

Guadalupe Avalos is a senior at Cass Tech High School in Detroit. Last April, she was just a few months into a part-time job as a barista before the coffee shop shut down and let her go. She didn’t even get to master the espresso machine.

“I was just learning to use that one,” she says.

Avalos asked about jobs around her neighborhood, like a nearby pizza place and a grocery store, but she kept being turned away.

“Yeah, there was a job at a McDonald’s, but it was 20 minutes away and I don’t have that kind of transportation available to me,” she says.

For Avalos finding a job is important: It may determine whether she’s able to pay for room and board at college next fall.

“I really, really want to move out and go to a college dorm room, but if I don’t have that money, then I might just have to stay home,” she says.

And that points to a reality for many young people. Failing to land that dream first job, whether in high school or college, can end up derailing a lifetime’s worth of career experience.

Economist Gould says the 2008 Global Financial Crisis might be an inexact comparison to the pandemic-scarred economy. But one thing it showed was how difficult it is to recover from the setback of starting your career on the wrong foot.

“It took many years for some of those young high school and college graduates to get their foothold in the labor market, to get on a path they’d been trained for, to pay off student loans, to start a family, to invest and buy a house,” she says.

Ha in Minneapolis has even more riding on finding that first job. He is the first generation in his family to graduate college, and soon, his parents will attend his socially distanced graduation to watch him get his degree.

And although Ha is unsure of what his future holds, he is still hopeful that all the student loan debt, the hours of studying and the hundreds of cover letters sent will prove worth it at the end.

“I haven’t given up,” he says. “I’m just going to keep applying until something hits.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)