The Fed orders another jumbo interest rate hike. Many are wondering what’s next

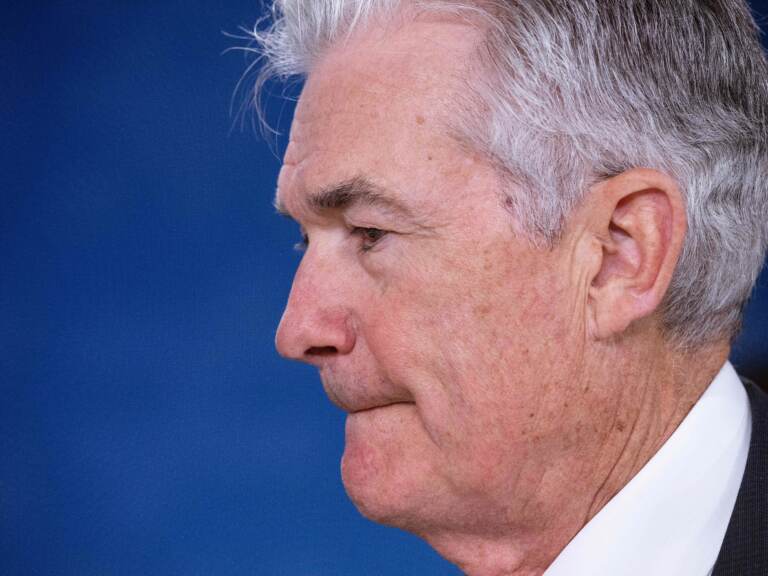

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell attends a meeting of the International Monetary and Financial Committee in Washington, DC, on Oct. 14. Powell announced another interest rate hike on Wednesday. (Jim Watson/AFP via Getty Images)

The Federal Reserve ordered another big boost in interest rates on Wednesday, and warned that rates will have to go even higher to bring stubbornly high inflation under control.

The central bank raised its benchmark interest rate by 3/4 of a percentage point. The rate, which was near zero in March, has jumped 3.75 percentage points in the last eight months. That’s the most aggressive string of rate hikes in decades, but so far it’s done little to curb inflation.

“Interest rates have risen at a whiplash-inducing speed, and we’re not done yet,” said Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate. “It’s going to take some time for inflation to come down from these lofty levels, even once we do start to see some improvement.”

Annual inflation in September was 6.2%, according to the Fed’s preferred yardstick — unchanged from the month before. The better known consumer price index shows prices rising even faster, at an annual rate of 8.2%.

Fed chairman Jerome Powell warned that taming such severe inflation will likely require even higher interest rates than he and his colleagues had predicted just two months ago.

“What I’m trying to do is make sure our message is clear,” Powell told reporters Wednesday. “We have some ground to cover with interest rates before we get to that level that we think is sufficiently restrictive.”

At the same time, Powell said the pace of rate increases may soon slow, as policymakers take stock on the effect higher borrowing costs are having on the economy.

“That time is coming, and it may come as soon as the next meeting or the one after that,” Powell said.

Stocks initially rallied at the hint of smaller rate hikes in December or January, but soon sank at the prospect that rates will ultimately have to go higher. The Dow Jones Industrial Average fell more than 500 points or 1.55%. The broader S&P 500 index fell 2.5%.

McBride argues that in order to curb inflation, borrowing costs will likely have to remain elevated for an extended period.

“The mantra for 2023 is ‘higher for longer,'” he said. “When inflation’s been running at 6, 7, 8% and the target is 2%, it’s going to take a while.”

Rate hikes are having an effect, even if inflation remains untamed

Higher borrowing costs have already put a big dent in the housing market. And other parts of the economy are beginning to slow. But consumers, still flush with cash saved up early in the pandemic, continue to spend money. As a result, the Fed may have to tap the brakes harder, for longer, than it otherwise would.

“We see today that there is a bit of a savings buffer still sitting for households, that may allow them to continue to spend in a way that keeps demand strong,” said Esther George, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. “That suggests we may have to keep at this for a while.”

Like her colleagues on the Fed’s rate-setting committee, George has expressed a determination to control inflation. But she’s also cautioned against raising rates too rapidly at a time of economic uncertainty.

“I have been in the camp of steadier and slower [rate increases], to begin to see how those effects from a lag will unfold,” George said last month. “My concern being that a succession of very super-sized rate hikes might cause you to oversteer and not be able to see those turning points.”

With polls showing inflation is a top concern among voters, the Biden administration and most members of Congress have stayed out of the Fed’s way as it tries to control prices. But a handful of Democrats have begun to challenge the central bank’s approach, warning that aggressive rates hikes could put millions of people out of work.

“We are deeply concerned that your interest rate hikes risk slowing the economy to a crawl while failing to slow rising prices that continue to harm families,” Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and colleagues wrote in a letter Monday to Fed chairman Jerome Powell.

The housing market has already slowed to a crawl, as mortgage rates top 7% for the first time in two decades.

Kansas City homebuilder Shawn Woods said his company has gone from selling a dozen houses a month before the Fed started raising rates to fewer than five.

“Never in my wildest dreams would I have thought we’d go from 3% [mortgage rates] to 7% within six months,” said Woods, president of Ashlar Homes and the Home Builders Association of Kansas City.

“I think we’re in for a rough six or eight months,” Woods said. “Typically, housing leads us into downturns and it leads us out of downturns. And I think from a housing perspective, we’ve probably been in a housing recession since March or April.”

Despite the fallout from rising interest rates, Powell said the central bank has a responsibility to bring inflation under control.

“No one knows whether there’s going to be a recession or not, and if so how bad that recession would be,” Powell said. “Our job is to restore price stability so that we can have a strong labor market that benefits all, over time.”

9(MDAzMzI1ODY3MDEyMzkzOTE3NjIxNDg3MQ001))