What we went through: The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary School — part four

Wister’s 5th grade students see themselves reflected in a faculty that has adopted a civil rights mission. And Jovan makes a major personal decision.

It’s a school day. Before dawn. The streets are mostly still, and teacher Bahir Hayes is getting himself in the mindset to do battle.

“We are fighting crime, poverty and deficits, and we’re trying to close the achievement gap. You have to mentally prepare yourself to get through this or you won’t,” said Hayes.

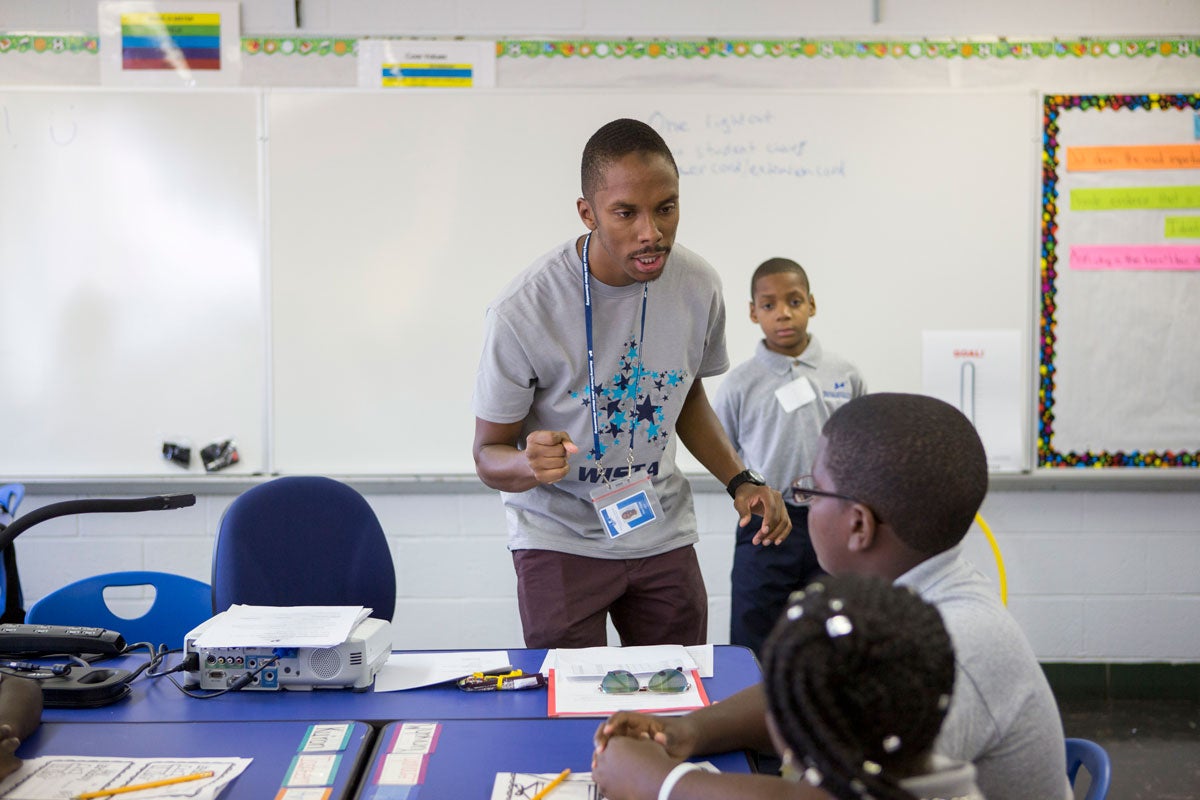

Hayes is the fifth grade english teacher at Philadelphia’s Mastery Charter School at John Wister elementary. It’s his sixth year in the classroom, and he’s learned that to do the job right, it starts as soon as you wake up.

“You already are putting yourself in the mind of a warrior. And that sounds real figurative, but it’s almost kind of literal. You are putting your armor on.”

He gets in his car, drives to the school. It’s silent. No music. No radio.

“You have got to be here before the kids do to greet them with a handshake and a smile,” said Hayes. “But let alone, the day hasn’t even started yet. This is just the preparation for the battle.”

He gets to school. Greets the kids. Already, there are landmines on the battlefield.

“They might have not ate breakfast. They’re coming in late. They may not get the lesson. Someone wants to be silly. There was a fight in the neighborhood. There were words that were exchanged days before that you didn’t know about that you have to stop and address,” he said. “That’s all a part of the battle, adjusting to your opponent — the opponent in a figurative sense of whatever is stopping you from the goal of getting these kids to where they need to be.”

In Philadelphia’s East Germantown neighborhood, those opponents are plenty. Generational poverty, substance abuse, violence.

And once the day begins, he’s immersed in this battle. He’s teaching lessons, diffusing problems, maintaining order in the lunchroom, coaching basketball during recess, sometimes talking with parents, doing grades, prepping. He can barely feel time pass.

“It’s like when a racecar driver is driving a car, while that race is going on, they’re not really breathing; they’re just driving,” he said. “And that’s what we’re doing. We’re not breathing; we’re teaching.”

Hayes, who also grew up in a low-income Philadelphia neighborhood, is out to show students that there’s another way, and that his english lessons can be as exciting as gym class.

“And in fact, it’ll take you even further, because if you utilize these skills I’m giving you, you’ll be able to find your own battlefield that you can fight on, and get the spoils of war. I am going too deep with this,” Hayes said, suddenly laughing at how far he stretched the analogy. “I actually just saw like a little preview of “Game of Thrones” not too long ago, so….”

The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary can also be experienced as a radio documentary. The tale is told across the four-episode second season of our podcast “Schooled.” It’s based on more than two years of reporting about the students, the parents, the faculty, and the huge political fight that sprung from Wister Elementary. You can listen using the play button above. This is part four, the finale.

Making the moves

Like Hayes, Wister principal Jovan Weaver knows well what’s at stake in this work based on his own childhood.

Standing on the block in Strawberry Mansion where he grew up, Jovan looked at the homes of some of his childhood friends. “My one friend who lived there was a terror,” Jovan said, gesturing down the street.

Many of those friends were swallowed up by the destructive forces of the neighborhood, and Jovan is determined to help his students at Wister avoid a similar fate.

“That’s the goal. Every day I keep pouring into them because every kid does have greatness inside of them, and it’s a matter of extracting that and nurturing and molding it,” he said.

To Jovan, providing those opportunities means taking the mission very seriously, and sometimes that means making really tough decisions.

That’s what happened with Nate Higgins, Wister’s fifth grade math teacher.

“He’s a great person. He’s passionate. Just had a really hard time executing,” said Jovan.

Higgins struggled to control his classroom through the first half of the 2016-17 school year. And internal data showed that the students were not progressing.

During the big public debate the prior year that led to Wister becoming a charter school, much had been made of the fact that only three percent of the students were proficient in math when the district was in charge.

Jovan’s goal was to get that rate up to ten percent, but, early on, it seemed the rate could stay flat or actually decrease.

So by winter break, Higgins was removed from the classroom.

“The data wasn’t coming back,” said Matt Rankin, one of Wister’s assistant principals. “We put a lot of supports in place for him, and a lot of coaching, a lot of feedback, and we just weren’t seeing that quick movement that our kids ultimately need.”

Higgins was demoted to a support teacher in the primary grades. After this happened, he declined to talk on the record.

But what happened here gets to the heart of the debate that sprung up around Wister. Charter school opponents often lament that charter teachers are younger and less experienced than those in traditional schools.

Robin Lowry, who was Wister’s phys-ed teacher when it was a district school, criticized Mastery for this during the debate.

“[The students] need experienced teachers not scripted novices,” Lowry testified at a School Reform Commission meeting in 2016. “Poverty is not an excuse to degrade, politicize or criminalize the most vulnerable students’ education.”

Wister parents like William Jackson had dismissed Lowry’s concern, and didn’t mind at all when it became clear that Wister’s new faculty was clearly younger and less experienced.

“That’s one thing that I am excited about: that there’s just such a younger breed. There isn’t the old way of doing things, the older teachers the old, obsolete way,” he said.

So what did Higgins’ demotion, four months into the turnaround, say about a conversion that that had been touted as transformative?

Should parents have expected more from Mastery than new teachers learning and struggling on the fly?

“I think that’s where the intense support comes in,” said Jovan. “[Parents] can see the support that all of my teachers are receiving and they’ll see the progress, they’ll see exactly the quality of the work their students are bringing home, see how much their students are growing.”

The way Mastery sees it, plenty of teachers in distressed urban schools, new and old, struggle to be effective every year. And many are left to languish without support.

So, to them, where another school would have left Higgins to flounder, they took swift, drastic action for the betterment of the school — a move that would no doubt have been more difficult if Higgins had union protections.

“We just need to put our strongest person in that role,” said Rankin. “It would be really hard for me to sleep at night if I sent our kids into middle school without those foundational math skills.”

There’s a tension here that all schools grapple with. Great schools don’t allow ineffective teachers to waste students’ time. But they also don’t make teachers feel expendable.

At Wister, Jovan and his team tried to walk that line — balancing the urgency of kids’ needs with the recognition that the job will be best done when professionals feel valued and empowered.

In this case, Jovan wholeheartedly defends the decision.

“We do this work to create a world-class experience for our kids. We do this work to see them grow. If you have an ineffective teaching in front of a group of kids, what type of impact is that having? It doesn’t make a lot of sense because then you’re right back in the same point, but not only that, now you have kids that’s another year behind,” said Jovan. “You keep plowing down this road, and then we wonder why our results aren’t improving. Why is that? Because people aren’t making the moves that needs to be made.”

There are plenty of good, effective teachers who would not feel comfortable working in a system like Mastery’s, one where pay is tied to performance and job security is no guarantee, as opposed to many traditional public schools where pay is tied to years of experience and education.

But for someone like Bahir Hayes it’s a major draw.

“When you incentivize teaching and you pay someone based on how hard they work, you’re going to get a better run school. You’re going to get a better-run classroom,” said Hayes.

An underlying truth here that transcends this debate is that schools serving lots of poor children struggle to attract and retain great teachers, especially in math and science. That goes for schools urban and rural — district and charter.

And in Pennsylvania, where teacher pay correlates highly with a district’s wealth, there’s less financial incentive for teachers to seek out and stay at the state’s poorest, neediest schools.

‘Who they really are’

What happened next at Wister seemed bound to fail — at least on paper.

Jovan decided to replace Higgins as fifth grade math teacher with someone younger, with even less experience as a teacher. Where Higgins has a master’s degree in education, the replacement was someone who was not even certified by the state — someone with a history of trying and failing to pass certification exams.

But, as is often the case, what’s on paper doesn’t tell the whole story. And Timeeka Benjamin, the replacement, can testify to that.

“I can relate. I am a girl, a black woman from an inner city who understands what it’s like to have a struggling mother with several children, who understands what it’s like to have an absent father, who understands what it’s like to see to see your mother struggle so hard that you’ve got to light candles all around the house cause your electric went off, or you got a boil water on the stove and put it in a tub because you don’t have any hot water….or your mom had to sell her food stamps to get your brother a winter coat. See, I understood and I know. I know why they act the way they act,” said Benjamin. “I know.”

Benjamin grew up in Norristown, and, after college, started her career as a substitute teacher. She then worked for years as a support teacher at a number of Mastery schools. When she was called up mid-year to replace Higgins, it was her first full-time classroom gig as lead teacher.

And from the get-go, it was clear to students like that she was in charge, and she wasn’t messing around.

“She kind of picked up the slack,” said 11-year-old Naiome Roberts. “When she came, everybody was, like, ‘Oh, Ms. Benjamin [is] here. Everybody be quiet, sit down.’”

Benjamin said differences in race and class between her and Higgins definitely played a part.

“I don’t think he could relate to them on so many different levels,” Benjamin said. “And so when you can’t relate, and the kids feel that there is no authentic relationship created, your classroom management is not going to be smooth, and classroom management, to me, drives instruction.”

She’s not saying that only African-American teachers can be effective with African-American students. That’s far from the truth at Wister, or around the country.

“It doesn’t matter what color you are because kids don’t see color. They don’t see color. They’re looking for somebody to love them,” she said. “It doesn’t matter what color you are because we have white teachers here who our kids absolutely adore.”

But the racial dynamic can’t be ignored. With Benjamin, Hayes, and the fifth grade social studies teacher, Shantel Shaw, who is also black, the nearly all black student body was well aware of who was teaching them.

When I sat down to talk with 11-year-old Malachi Oduardo, it came up within the first few seconds.

“All three of our teachers are African-American. So, they know what we went through,” he said.

Naiome Roberts brought it up unprovoked as well.

“Like all of fifth grade, we got a whole [teacher slate] of black people,” she said. “So it’s like they know what we go through, and it’s like they love on us more.”

Many teachers I spoke with at Wister emphasized the idea of education being the defining civil rights issue of our time. For Benjamin, each day’s class was an opportunity to give students the skills needed to overcome a history of oppression and injustice — even if that meant sometimes deviating from curriculum.

“I said, ‘You know what, put the books away. You need to learn about what’s going on in this world right now.’”

Benjamin would address race and social justice head-on was, talking about both current events and history. Doing this, she says, was the reason, ultimately, for her success — with metrics showing that many more students were learning from her.

“When I give those lessons about life and I give them examples of black people who fought for them, I tie it right into a math lesson,” she said. “And you know what: when we’re reopening books, twenty minutes ago my kids wasn’t getting it. Now, because I planted the seed in their mind and I built their confidence by telling them who they really are, there’s no playing around. That’s why my kids went from zero percent proficient on their periodic [assessment] to 35 percent in five weeks — because I taught them that.”

By framing her lessons this way, Benjamin said the students became much more motivated.

“They understand that, ‘Hey, I don’t have time for mess-ups, I don’t have time to play around. I got to come in here and I got to do my stuff and do it right. And I got to get these grades because this can no longer be my reality,’” she said. “‘If Ms. Benjamin could do it, I could do it. And Mr. Hayes could do it, I could do it. If Ms. Shaw could do it, I could do it. If Mr. Weaver could do it, I could do it.’”

Truest form

No school year is a sprint. They’re all marathons. And each has its ups and downs for both students and teachers.

In Bahir Hayes’ class there were plenty of ups, like when kids would really get into the books they were reading. Or like when his english class scored higher on an internal test than any other Mastery fifth grade class.

But things weren’t all rosy. Some kids struggled with the lessons throughout the year.

“You can see that their grammar is off and they need explicit, deliberate practice,” he said. “Or else sometimes their writing is not as clear as it could be.”

There were behavioral problems to deal with, and sometimes students flat out wouldn’t want to work.

“They’re going to have issues. They’re going to have these really have meltdowns. That’s not a result of bad teaching. That’s not a result that things aren’t working. That’s a part of this process. In order to get these kids where they need to be we need to know who they are in their truest form,” he said. “There will be days when kids don’t want to do it. But what you should see even if a kid doesn’t want to do it, is a teacher trying, a teacher walking over and not just letting their child lay there.”

That persistence in the face of difficulty is large part of what makes working in high-needs schools really tough. Even if you’re really good, even if you really care — maybe especially so — it’s a grueling gig.

“We talk about this idea of emotional constancy, but this is an emotionally draining job,” said Jovan. “You just feel a heavy burden to succeed. You feel the heavy burden to serve this community. You feel a heavy burden to serve these kids. You feel a lot of pressure.”

For Jovan, the year was particularly difficult with challenges in his home life. He and his wife of nearly a decade had split up just after he became principal, and he poured his soul into the school as he sorted through the emotional mess of a divorce — trying to be super-dad for his two young children and super-leader for his 522 students.

“I chose a life that would impact other lives. And maybe this is part of the cost for that,” he said, choking back tears. “But at the end of the day, if thousands of children can say that, when they’re older, that Mr. Weaver motivated them to do this or I remember this…”

Jovan trailed off, thought for a moment, and then wondered aloud.

“Is it worth having your family torn apart?” he asked, his voice tightening. “How do you answer that? I don’t know how to answer that. I don’t. Because it was not a conscious choice that I made. I didn’t say, ‘It’s either principal or my family.’ That would never be the case. That’s insane.”

The divorce forced Jovan to grapple with things deep within himself, to recognize that his painful childhood has left him with a lot of trust issues and insecurities that have proven very hard to shake.

And as successful as he is in the many things he does, there’s part of him that feels forever dogged by the shadow of the traumatized boy he once was.

“I still have a lot of those issues, current day,” he said. “And I try to be so reflective, and I try to make so many connections, questioning, like, ‘What’s the common denominator? Is it me? Is there insecurity there that I haven’t explored. Are there some blind spots that I’m still not seeing, where think I’m super reflective but I’m not? Why do I keep finding myself in the same position?’”

No matter what was happening in his homelife, Wister was a haven for Jovan. It was a place where he could focus all of his energy into something positive, a place where he could shelter and enrich all those smaller versions of himself he saw walking through the halls.

Intentionality

By Spring of 2017, it was clear to many parents that Jovan and Mastery were delivering on their promise.

“I just like the communication that we have as teacher and parent,” said Tamira Simon, mother of fifth grader Semaj Watson.

During the conversion debate, Tashiana Gaines, mother of five students, including fifth grader Sunset, said she was neutral. District or charter didn’t matter to her. She just wanted to see the school improve.

She says under Mastery, her children get more support and are more excited about school.

“They’re more motivated,” she said.

Malachi Oduardo’s grandmother, Valerie Leggett, was stunned at the difference. In previous years she would get multiple calls throughout the day from either Malachi or the faculty with some sort of complaint.

“The difference is he got the help that he needed. He got the attention he craved so much,” said Leggett. “[In previous years] he’d get upset, and walk out the classroom when he’d want to walk out. ‘But you can’t do that, Malachi. You have to listen.’ So this year, he listened. I’d check my phone, ‘Oh, Malachi didn’t call me today.’ Amazing. Amazing.”

Grandparent Denise Sanders praised the new the staff for emphasizing positive “community values of how to keep your surroundings clean and being kind.”

But not everyone gave glowing reviews.

One grandparent who requested anonymity had nice things to say about Jovan and some teachers, but complained about how some of the school’s lower-ranking support staffers have interacted with students, saying they weren’t qualified. This person was against the charter conversion from the start and remains distrustful of Mastery — wishing Wister was still a district-run school.

Eve Roberts had three kids at the school, including fifth grader Naiome. She offered one of the most nuanced perspectives of all parents I interviewed. She’s very sympathetic to the former staff and principal, but in the end very happy the transition occurred.

She was afraid when Mastery came in it would be overly rigid, especially with her one son who she knows can be a behavior problem. But she’s been impressed.

“They work with him,” she said. “A lot of times I’ve learned that it’s just simply engaging the child to find out what’s going on.”

Roberts says a lot of the difference in the school came down to Jovan setting the right example.

“Principal Weaver operates in excellence. Plain and simple. And it’s obvious,” she said. “You can see it in his overall demeanor, how he conducts himself, how he carries himself on in children. You can see the support. You can see the fun. You can see the sincerity.”

Creating a successful school is not unlike what it takes in other jobs and projects. Do you have a smart plan with buy-in from talented people up and down the ladder? Do you have the resources needed to execute that plan with fidelity? Leadership to see it all through?

“I think that’s the difference with a great school and a struggling school: is that you have to have a system that puts your teachers in the best position possible to be successful,” said Hayes, “which ultimately puts students in the best situation possible be successful.”

For all the tension in the district school vs. charter school debate, the simple role of scale here can’t be ignored. That having a great plan and executing it — putting teachers in the best position — can be a lot easier when you’re running one school, or twenty-something, like Mastery, compared to over 200 that the School District of Philadelphia runs.

That was a lament of Wister’s former principal, Donna Smith. When we talked after the conversion was first proposed, she complained that the superintendent and the district’s central office had been disconnected from the school.

“He’s never been here,” Smith said of Hite. “Come out and see for yourself what goes on in my classrooms. Or, how about this, add to what I try to do for literacy and math and tell me what I need to do to strengthen children, teachers, classrooms in order to make it a better environment for kids.”

Under Mastery, it was a very different story. It was clear that the top administrators knew intimately the challenges the school faced and actively worked to give Jovan the structures and support the school needed. The teachers were trained specifically for the task of serving high-needs students, and you could see the intentionality in the design all the way down the line.

‘The game’

When standardized testing time comes around in a school, it takes over. And, in April, Wister students sacrificed nine days of instruction to take state-mandated tests.

Ultimately, these nine days carry a lot of weight.

After all, it was what students did during those days a few years back that had a lot to do with Wister becoming a charter in the first place. And this year — no matter what else happened in the school — many would also judge it by these nine days.

“It is high impact. It’s stressful. But is it frustrating? No,” said assistant principal Matt Rankin, “because at the end of the day, that’s the bar we want to hold our kids to. The assessments ask kids to write and read and think really deeply about things, and we do want our kids to be successful for that.”

From what I saw, while Mastery was not the test-obsessed organization that many critics described it to be, the school certainly took the tests very seriously. Some lessons were planned in order to prepare kids for material the tests would cover. Teachers worked to convince students to try their best. And activities and rewards were planned each day after testing to give students something tangible to work toward.

“Is it tough to get kids motivated over nine days of testing? Absolutely. Did we think really strategically about that? Absolutely,” said Rankin. “So we had a lot of incentive programs. We had things where kids earned an incentive at the end of each day. So they made slime or they had a movie day in the theatre.”

Bahir Hayes is a testing skeptic. He remembers taking these same tests himself as a kid, not doing well, and feeling like they weren’t a good gauge for his potential. But, the way he sees it, they come with the territory.

“If that’s the game, and that’s the way the game is set up, then I do want to prepare [students] for the game,” he said. “What kind of coach would I be if I’m not preparing and what a good game plan, you know, honestly?”

Timeeka Benjamin, the math teacher who came in mid-year, was much more critical of the process, especially because she was on the low end of Mastery’s merit pay scale and fearful that her students’ scores wouldn’t reflect her hard work.

She has her own young daughter and a mountain of college debt, and felt this anxiety throughout the year.

“I’m not saying don’t teach them reading, writing and arithmetic, because they need that to even do anything, but what I’m saying is, ‘Why are you making that, like, such a competition? And it’s hurtful to our kids because it stresses the teachers out. Because now they’re like, ‘Ok, if you don’t pass, then I’m not going to get paid. I’m not going to get a raise and I’ve been busting my ass all year.’”

Holding hands

It would be months before the results of those tests would come in, but Bahir Hayes didn’t need to see them to consider the year a success.

He knew the growth that the fifth graders had made, not just academically, but as people, and that included a young girl named Eirkka.

“We had a lot of trouble this year with fighting. Trust issues, just issues at home,” said Hayes.

Eirkka was a behavioral problem throughout much of the year, but Hayes made it his mission to bring out something better in her.

“Most people would give up on Eirkka. I refused to. We refused to as a team. We refused to as a school. Most people would have kicked her out,” he said. “But that’s a part of growth and that’s a part of being there for someone and being a family — recognizing that this child is not really bad. This child is going through something. This child needs us.”

By the end of the year, she started opening up more with her teachers, and started treating her peers better, which Hayes called “a major victory.”

And at the fifth grade graduation, it was Eirkka and another student, Sanaa, who she had fought with all year long, who opened up the ceremony — the two of them standing side by side.

“Good afternoon ladies and gentleman! Are you ready to get this graduation started?” they said.

Graduation was held on a hot day in June in the sweltering Wister auditorium. Hayes was the emcee.

“Give it up for heat!” he said over the P.A. system, laughing wryly.

There was a slideshow. Awards were presented. And students and teachers gave speeches. Naiome Roberts delivered the keynote.

“I walked in this new school and I felt welcomed. I’ve been going to this school since first grade, and I never felt so much love in one school year,” she said. “That’s why it’s going to be really hard for me to say goodbye and leave.”

Student Zahkiyyah Frazier got very emotional at the podium.

“This was one of the best years I could ever have,” she said, through tears.

Timeeka Benjamin poured her heart out as well.

“What’s understood don’t gotta be explained. To all my kids, ya’ll already know what time it is. Ya’ll know I love you so much,” she said, quaking with emotion. “There’s nobody on this earth greater than you. There is a champion in every single one of you.”

Bahir Hayes used his time to talk about Eirkka and Sanaa, explaining to the audience that they had “beefed everyday.”

“But today these two young ladies were able to come in here together holding hands,” he said, as the packed auditorium began clapping. “And I believe that’s why we do what we do, because we want to make sure we see the change in these neighborhoods. There’s a lot of violence in our neighborhoods, a lot of crime. A lot of fathers who aren’t there for their kids because the system takes them from them. But I feel like this is the future of what we’re trying to build here at Wister. We want to teach our kids to solve their problems without hurting each other, killing each other and shooting each other. And I really want you all to clap it up for these two young ladies because too many times this goes a different way, and they made it work.”

The numbers

Just after the school year ended, Jovan received the school’s standardized test results.

“I was ecstatic,” he said. “The amount of work we’ve poured in this year. If results or gains weren’t made, it would be a different feeling.”

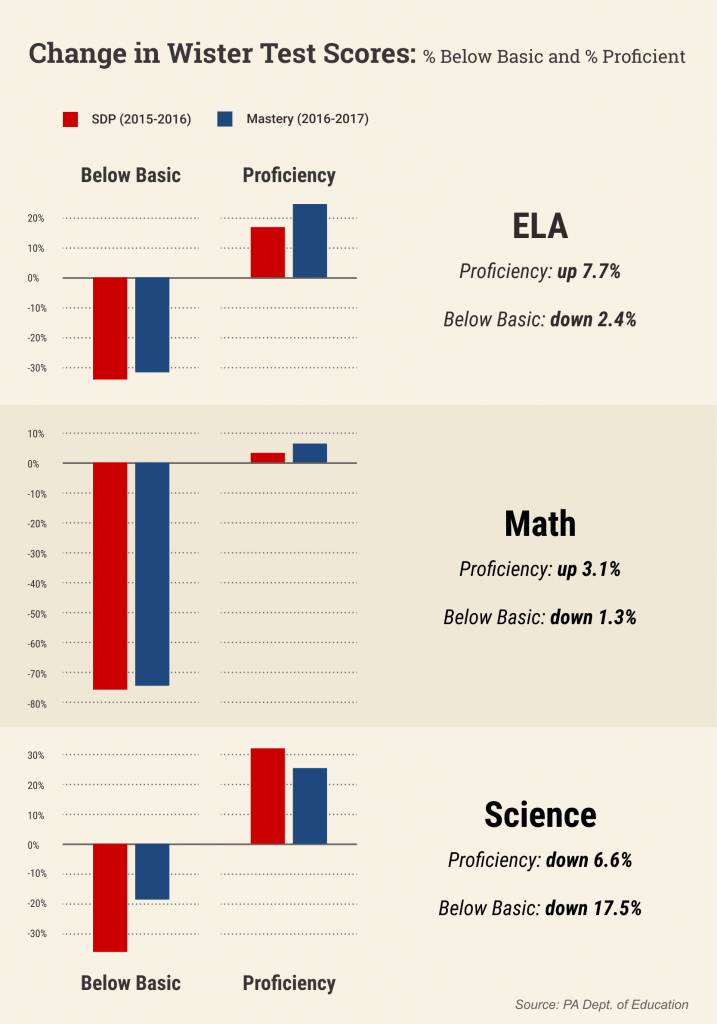

Compared to the prior year, the school saw an eight-percentage-point jump in english proficiency rates, a three-percentage-point jump in math proficiency rates, and a seven-percentage-point drop in science.

In all subjects, a smaller percentage of students scored in the very lowest “below basic” category.

The fifth grade mostly followed the larger testing trend, but the gains made in Hayes’ English class were nearly double the school average, confirming what he told me on the very first day of school.

“It’s not on my mind, at all. Not thinking about that. Because if I do what I’m supposed to, that chart is going to go up regardless,” said Hayes.

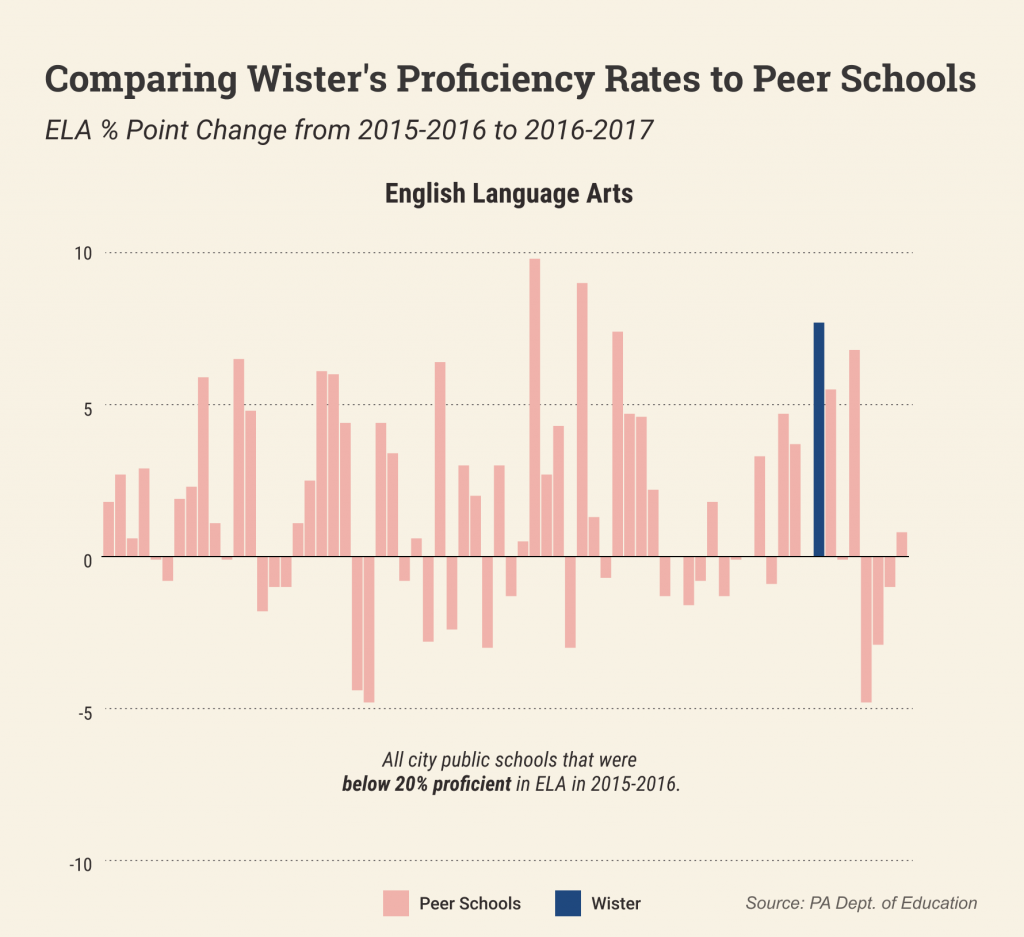

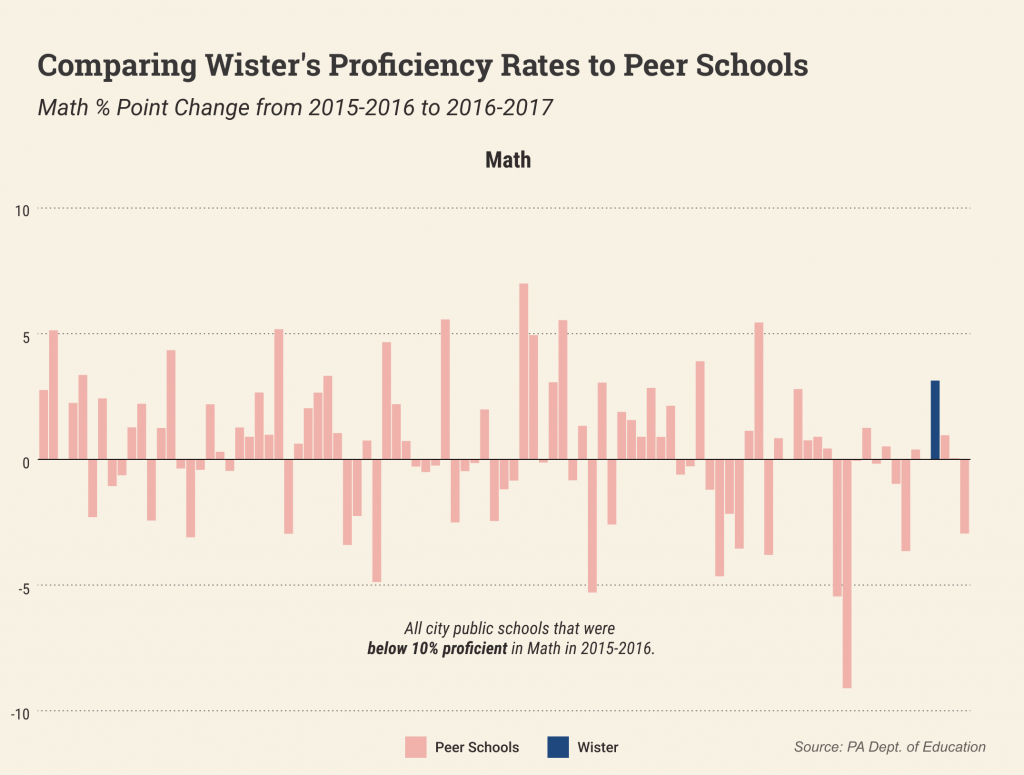

In Math, although the gain could seem meager, and although it fell short of internal goals, it is significant, especially in context.

Compared to the dozens of other schools in the city that started close to where Wister started in both math and English, many went backwards. And only two other schools in that group posted the sort of gains that Wister did in those subjects.

That’s no small feat. But let’s also be clear, the students in these schools are still far behind peers in wealthier, often whiter neighborhoods. And for Jovan’s team to get anywhere near closing that gap at Wister, it’ll will take a determined and concerted effort year after year after year.

Suspended?

Some other data for Wister came back less flattering, namely, student suspension rates. Numbers published by the Pennsylvania Department of Education show that the out-of-school suspension rate under Mastery tripled compared to the previous year.

To some, this may make plenty of sense. Detractors often criticize charter schools for suspending students too frequently. And even charter supporters say a school in the first year of a turnaround is likely to see a spike in suspensions as leaders try to enforce stricter behavior expectations.

But the numbers came as somewhat of a shock based on anecdotal interviews with Wister students and parents.

One grandparent did say Mastery suspended students over “stupid stuff.”

But many others said the complete opposite — that it was their perception that suspensions had dropped compared to when the school was under district control.

“[Last year] we had little discipline and all it was was, ‘suspend, suspend, suspend,’ back to back, so it would go on our record and look like we were bad children,” said student Naiome Roberts during her graduation keynote speech. It was an idea her mom, Eve, echoed.

Student Tatiana Hubert also agreed.

“If there was a problem [last year], they would suspend both of us that was in the situation instead of talking about it.”

Malachi Oduardo and his grandmother said he was suspended a half dozen times in previous years, which put a major strain on the family, pushing parents to miss work. Under Mastery, he wasn’t suspended at all.

“I’m an upstander,” he said. “I help people when they are getting bullied.”

Jovan was also surprised by the story told by state’s numbers. He couldn’t offer an explanation other than to say that it’s his goal to suspend as few students as possible.

Mastery CEO Scott Gordon questioned the integrity of the data, noting that the state’s “safe schools” review is based entirely on self-reported data, leaving room for error or malfeasance.

Year two

The second year of Mastery at Wister started with much less fanfare than the first. And Jovan’s job was to maintain the high energy and passion of the first year while pushing for even better results.

“The honeymoon is over now,” said Jovan. “Year one is easy to quickly change the dynamic and rally around things.”

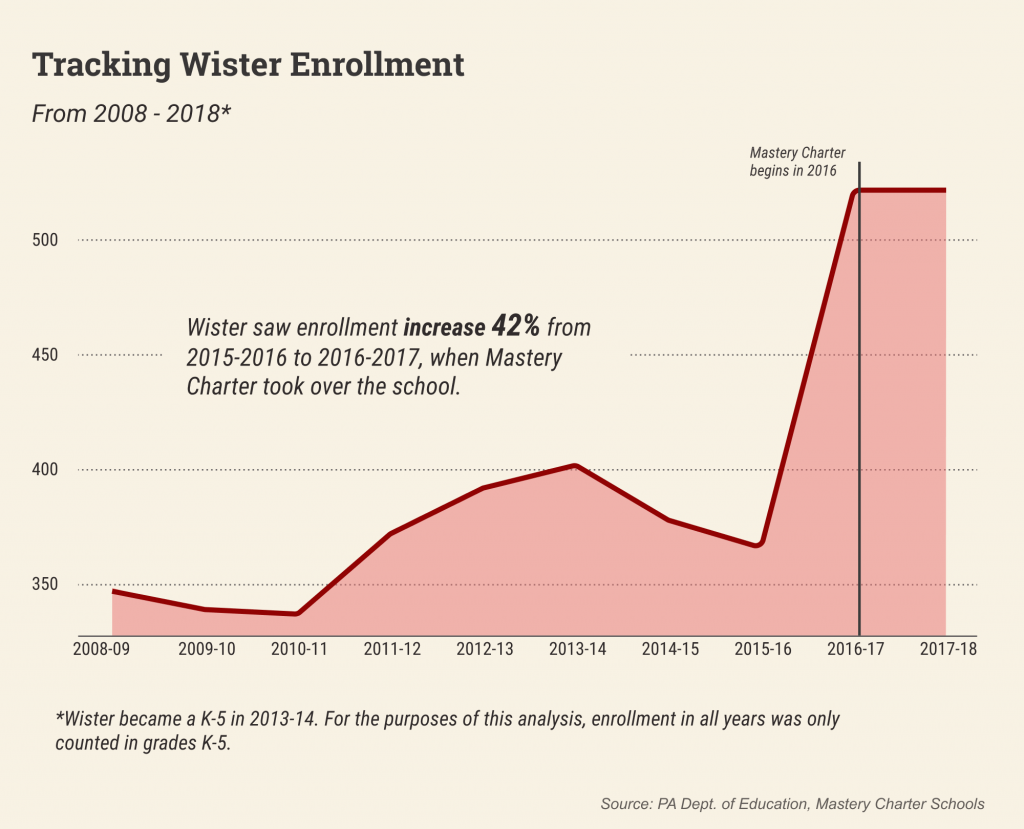

In an encouraging sign for the school, enrollment held steady in the second year of Mastery, a fact CEO Gordon says speaks volumes.

“That is democracy and, in the messy process of public education, the best outcome one could possibly hope for — that parents get what they want and it begins to change the neighborhood,” he said.

Most of Jovan’s staff stayed the same.

Assistant principal Matt Rankin is still there, a key part of the concerted effort to close the achievement gap.

“Do I believe that our kids have the potential to do what any other kid in our country can do? One hundred percent, yes,” he said.

Timeeka Benjamin, who’s still hoping to earn her certification, is now teaching fourth grade math.

“I’m not going to stop until I’m dead in my grave trying to fight for equality for these black kids,” she said.

Benjamin’s predecessor, Nate Higgins, was not invited back. He now teaches in an elementary school in the Philadelphia suburbs. He says he loves his new job and has no ill will towards Mastery.

In a blow to the school, Bahir Hayes also left Wister. He accepted a job as a principal fellow in a struggling school run by the school district, bringing his charter school experience to a new, but very similar student body.

“These kids were always smart. I’m not naive to think that they weren’t — that we just had a magic bullet,” said Hayes. “They just weren’t given the opportunity to show who they were. Someone didn’t take their time to tell them or show them or discover what it was about them. Because you can’t just tell a child they’re smart. You have to let them know why. And that takes time, and it takes the battle.”

To outsiders, Wister is still a flashpoint in Philadelphia’s larger school choice debate.

Councilwoman Helen Gym pinpoints the controversy surrounding the Wister conversion as one of the culminating reasons why the power dynamic in Philly school policy has dramatically shifted recently.

The state-controlled school board that had approved the Wister conversion is in the process of disbanding, being replaced by a board expected to be less friendly to aggressive school interventions.

“It’s the reason why they’re gone,” said Gym. “No matter what decisions were made at that point, they are a sign of school governance system that is in the past and has ended for that very reason.”

Since Wister, the district hasn’t proposed another charter school conversion, and Wister seems poised to be among the last class to go through — at least for a while.

Back in October 2015, Philadelphia Superintendent William Hite had proposed three.

One conversion was greenlit by the School Reform Commission, but then the charter company backed out of the deal a few weeks later. The school stayed under district control and saw test scores decline.

Another school became a charter, but also saw test scores go down.

And the third was Wister.

Those odds may not sound good, but when you are talking about what to do about chronically struggling schools, proponents say this kind of drastic action is still worth trying.

“I think it was the right thing to do,” said Sylvia Simms, the former school commissioner who played a large role in making Wister a charter school. “I think if it stayed a traditional public school it would be on the closing list because families people don’t want to send their child into a failing school. They really don’t.”

Jovan Weaver has a story to tell.

Not just as a boy who lived through trauma, not just as a principal of a school fighting to be transformative.

But as a parent.

On a recent morning, Jovan and his kids rushed through the family’s school day routine.

“Well, got the kids right now. Ariel’s getting dressed. Jace is washing his face, brushing his teeth, about to get some lunch together and get the day started,” said Jovan as he made sandwiches on a sleek kitchen countertop covered in kids’ snacks.

As year two began, Jovan moved into the Wister neighborhood, and he and his ex-wife, Frances, decided to send their own two kids to the school. Both children live with Jovan for most of the week.

“I always wanted to send my kids to the best schools,” said Frances. “That’s why we originally moved to Delaware. But I was into the idea of Wister because I trust Jovan. He handpicks his teachers — I love them — and he’s an excellent judge of character. So, it was a tough decision, but I’m really glad we made it.”

Jace, who showed off his ‘Black Panther’ toy, is in kindergarten.

“My teachers are nice and my dad is the principal,” said Jace, his young face beaming.

Ariel is in fifth grade.

“He’s embarrassing at school. It’s how he dresses and things like that,” she said of her dad, laughing. “It’s not good.”

Each day, the kids pile in dad’s SUV and arrive at the school in mere minutes.

Before long, Jace and Ariel go off on their own way to their homerooms, with Jovan giving them a little hug before they go.

“It’s been interesting, because they’ve been exposed to a lot,” said Jovan. “So we’ve had a lot of great conversations about certain dynamics and why certain classmates may behave a certain way, or why certain things are happening and what certain things mean. I feel like that exposure has really enlightened them to the world.”

As the day begins, Jovan goes to Wister’s front door to greet every student as they arrive — knowing his own kids are now just two of the hundreds under his care.

“It wasn’t about proving to anyone else. It was a matter of, like, ‘What we’re trying to provide here is enough for my children. And if it’s good enough for my children, it’s definitely going to be good enough for your children.’”

—

This special online presentation of “Schooled” Season 2 was produced by WHYY in Philadelphia for Keystone Crossroads, a partnership of Pennsylvania public media stations. Evan Croen was the digital producer. Photographs were taken by Jessica Kourkounis, Bastiaan Slabbers, Lindsay Lazarski, Kimberly Paynter, Emma Lee and Kevin McCorry. Graphics were created by Azavea. Charlie Kaier was the sound engineer and mixer for the podcast. Amy Xu was this season’s intern.

The season was made possible through support by the William Penn Foundation.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.