Jovan Weaver could barely sleep before his first day of school as principal.

“I was like a kid on Christmas Eve,” he said, laughing.

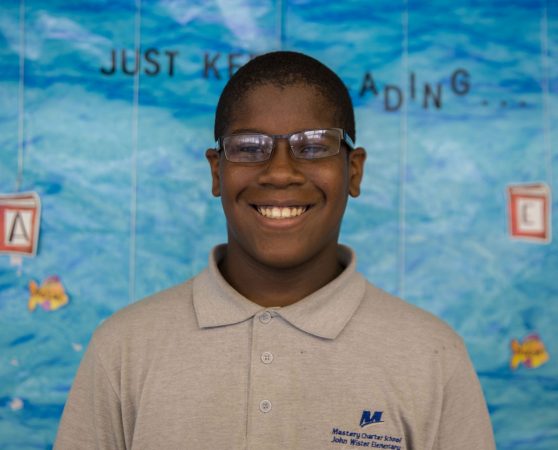

This was August 22, 2016 at Philadelphia’s John Wister Elementary, and the building was brimming with energy. In bright morning sun, small children swarmed the entrance wearing uniforms of Mastery gray and blue, their cartoon bookbags tight on their shoulders. Teachers cheerily greeted the children and pointed them to their homerooms. Parents idled at the foot of the school doors, watching as their little ones turned into Wister’s main hallway, disappearing from sight.

Every first day of school can be like a rebirth, but this one was especially significant.

The city had just endured a contentious and still controversial debate that led to Wister’s conversion from traditional district school to a charter run by Mastery Charter Schools. Now, formally, the school would be known as Mastery Charter School at John Wister Elementary.

And Jovan and a staff completely new to the school had worked frantically over the summer to get things ready for this moment.

“Right now, it’s game time. Everything was kind of leading up to today,” he said. “And now the real work begins.”

Coming into the change, a lot of promises and expectations were set: higher test scores, safer school culture, and ultimately, a school that would help the mostly poor student body defy the odds.

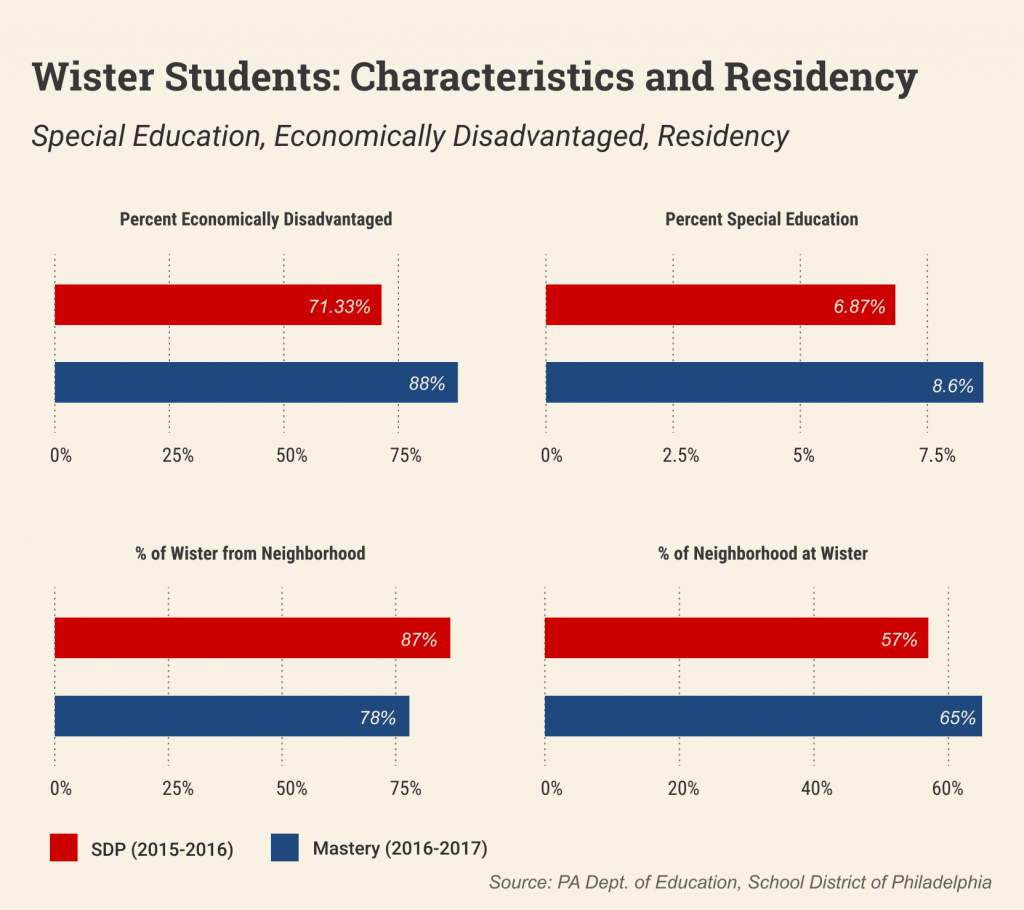

And many parents bought into this promise. Enrollment shot up by 150 students, with more of the families in the neighborhood opting for the school.

The job looked to be getting harder, as statistics showed the student body becoming even poorer and more challenged by special-ed needs.

“I can’t be in 19 classrooms at one time,” said Jovan “My teachers are on the frontline. They’re bearing the brunt of everything, and I just got to make sure that they feel supported, and they’re ready to rock for our kids.”

Mastery is the largest charter organization in Philadelphia. Its motto is: “Excellence. No excuses.” Over the years the organization has become something of a lightning rod. Supporters praise it for creating better neighborhood schools in the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Detractors criticize it for being overly rigid, and too focused on measurable data like standardized test scores.

Jovan became Wister’s principal as Mastery had self-consciously reevaluated its philosophy, and he adopted a different tagline: “Love and positivity.”

“I do think I represent a shift that Mastery is taking on as an organization, and it’s all about, just, love, building relationships, understanding our kids. While at the same time having super high expectations for academics and not lowering our bar one bit,” said Jovan. “But there’s also a qualitative piece there. You can’t always just be so data driven that you miss the human side of things. So I’m big on that. It’s a balance.”

For Jovan, personally, finding the right balance was very important. He grew up poor in Philadelphia during the crack-cocaine epidemic, and had overcome a childhood of trauma and neglect in no small part because of caring educators who both supported him and demanded more from him.

And now as an principal, he carries his past with him in everything he does, and based on his ability to relate to kids, especially troubled ones, he’s has garnered a nickname: “the student whisperer.”

On the first day of school, I saw this side of Jovan in action. A student named Kassir had been disruptive and was bullying other students, and Jovan happened to be walking by when a teacher was talking to Kassir in the hall.

“And the first thing I said to him is, ‘I don’t even know what happened. I have no idea what happened, but let’s just sit down and figure out what happened,’” said Jovan.

Jovan explained that Kassir was in “last year’s mode.”

“So me just sitting there and saying that to him, ‘Kassir, this is a new year. That was last year, this is the new you, and I need to see the best Kassir. That was not the best Kassir.’ That resonated with him.”

After his conversation with Jovan, Kassir went from sulking angrily, sitting on the ground, frowning, to smiling and agreeing to rejoin his classmates.

“It’s a new day,” said Jovan.

The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary can also be experienced as a radio documentary. The tale is told across the four-episode second season of our podcast “Schooled.” It’s based on more than two years of reporting about the students, the parents, the faculty, and the huge political fight that sprung from Wister Elementary. You can listen by using the play button above. This is part three.

So far in this story, we’ve heard many different voices. Namely, Jovan, but also parents, grandparents, district teachers, charter teachers, advocates, activists, politicians, district leadership, school board members.

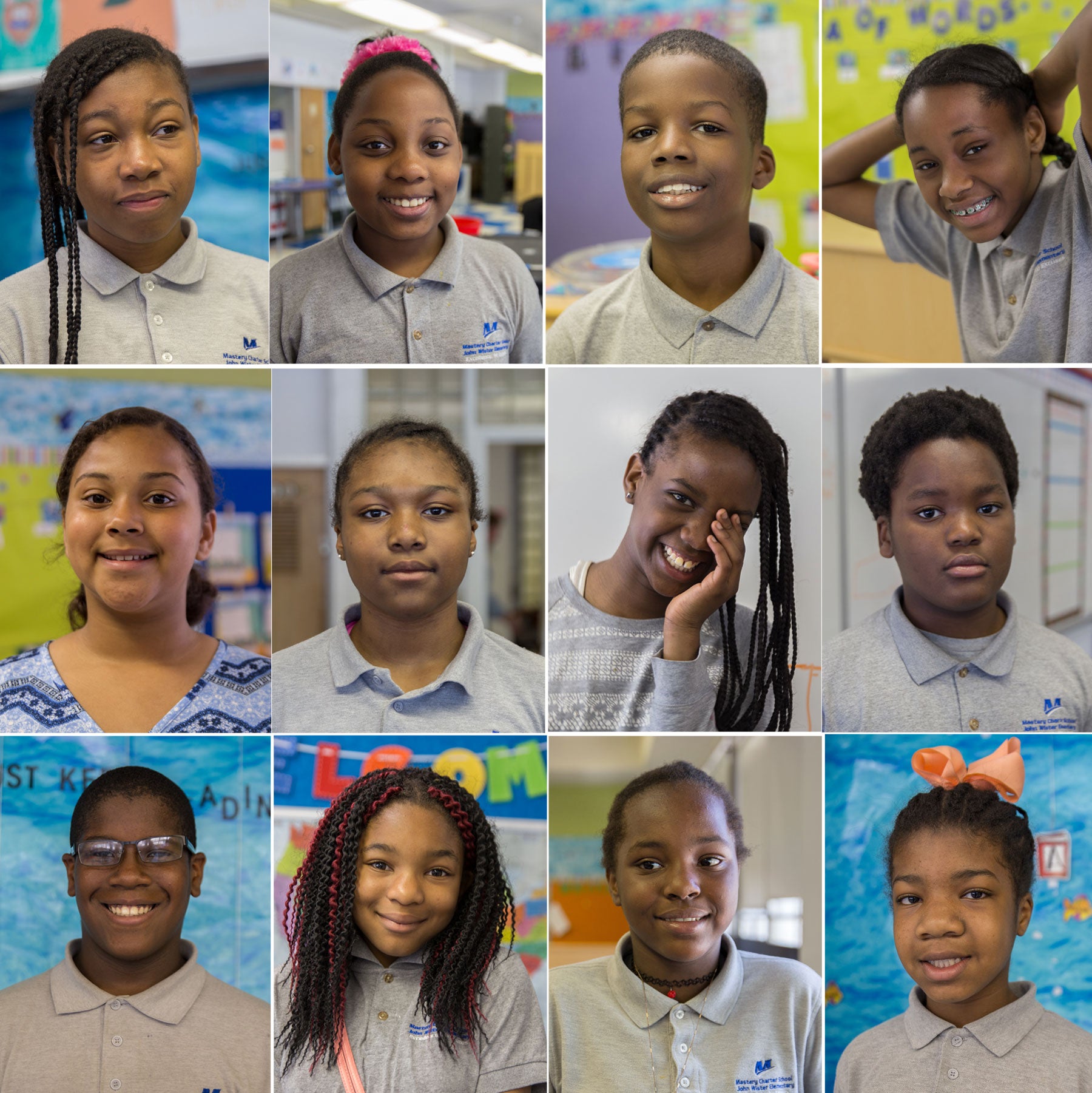

But there’s one group we’ve heard little from: students.

“Last time I was here for first [grade] and second, and half of third. It was ok, but I was messed with a little bit. That’s why I was homeschooled for a little bit of third and a little bit of fourth,” said 11-year-old Akasha McMichael.

“I was a fighter and I got into arguments. But now that I know that it makes my mom mad and she cries about it I don’t want to fight anymore,” said Malachi Oduardo, also eleven.

“Since I was, like, two years old. All I want to do is dance. My mom would take videos on me and she would post on Facebook and all that stuff,” said Shikier Anas Richardson. “All the time when I’m home I dance. I practice every day.”

“I’m not a troublemaker. I don’t like doing that stuff. My mom don’t play that,” said Naiome Roberts. “I want to grow up to be a person that always makes a change, like, always stands out from other people.”

“This summer, like, a six year old got shot. It feels sad, and sometimes I feel hurt because he was only 6 years old,” said Tatiana Hubert, referencing the boy in the neighborhood who had recently been struck by bullets ten times in the midst of a shootout near the school. “I don’t want to die too early before I even do what I have to do in this world.”

Each of these students was in the fifth grade. That was the class I focused on over the course of the 2016-17 school year. Wister is a K-5 school, so the fifth graders had been there under district control the longest. And as Mastery attempted to change the culture of the school, in theory, they’d be the hardest students to sway. They’d also be the most aware and able to vocalize how the school was changing.

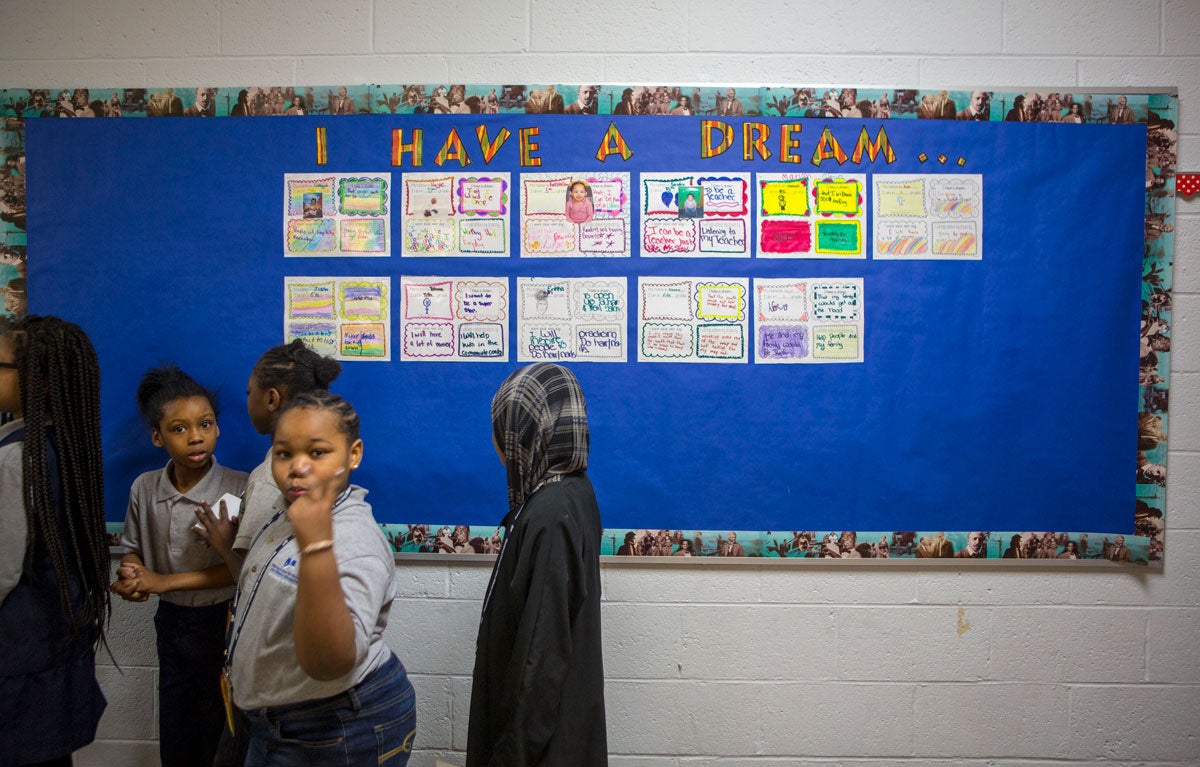

“Last year…everything looked plain and boring. And I walked in for my first day back, I went in the school and, like, ‘It’s bright, it looks happy and it don’t look gloomy,’” said Naiome Roberts. “I’m, like, ‘Wow, that’s a big change.’”

With school turnaround work, the thing that typically is most noticeably changed at first is the school building. When Jovan first visited Wister, he was shocked at the unclean condition of classrooms and the disrepair of the bathrooms.

“Walking through this building and just thinking, ‘My goodness, kids actually went to school here, kids actually had to sit in this classroom, kids had to walk into this bathroom.’”

Mastery poured $1.4 million dollars into the building to make it cleaner and brighter. They also bought new furniture, computers, books, and supplies and did it all with the help of a big start-up grant from the Philadelphia School Partnership, a well-endowed philanthropic foundation in the city that supports school choice.

The promise of this money clearly helped get people excited about Mastery during the conversion debate, as parents like Alicia Grant testified during the rancorous school board meetings that led to the charter taking over.

“Mastery put it in writing that they are willing to offer $1.5 million in grant dollars already to make this a change,” yelled Grant. “Mastery has their plan on the table. The school board do not.”

If you care about one of the many other public schools in Philadelphia that sit in disrepair, this sort of cherry-picked philanthropy can feel patently unfair.

But for the students and parents at Wister, it’s clearly a huge plus.

“They painted it. The bathrooms look nice. They did the floors in the gym room where they have lunch. They have a desk as soon as you walk in with somebody sitting there to greet you. Very welcoming,” said Anna Figueroa, a grandmother to five students.

A pretty building, though, does not a good school make.

That, of course, really comes down to the effectiveness of the educators inside.

And, at Wister, to understand this, we looked at two of the 5th grade teachers — both men in their late-20s, but worlds apart based on life experience, and, ultimately, effectiveness.

The natural

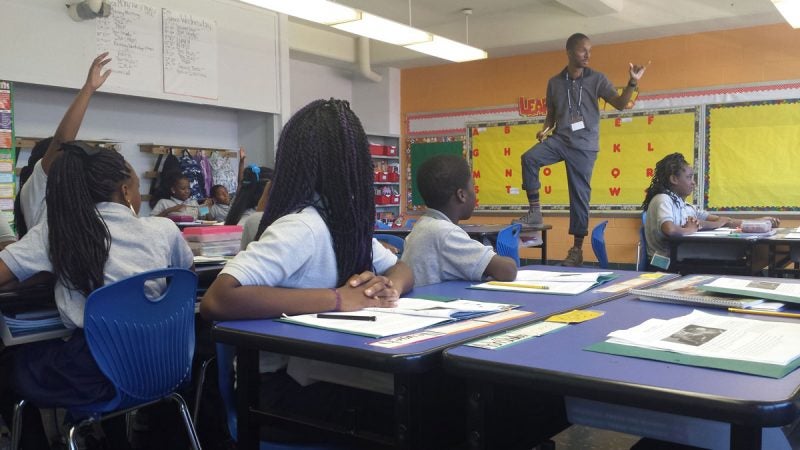

At the end of a long hallway on the 3rd floor of the school sat the classroom of english teacher Bahir Hayes. He’s lanky with an idiosyncratic style and a dynamic voice that ranges from a subtle whisper to a startling shout.

His classroom is his dominion — a space he moves through naturally, a place where he lives his conviction.

“I became a teacher because three of my little cousins’ fathers were murdered. And it was at that time when they didn’t have a father, they needed someone like me. And I’ve realized that there’s probably way more kids like that out here,” said Hayes.

With Hayes, Wister had a teacher very much in Jovan’s own mold, an African-American man who grew up in a poor section of Philly, made it to and through college despite the odds, and understands intimately the struggles that many students face in their home lives.

“I have multiple members in my family who are incarcerated. My uncle died in jail because he had ‘life.’ So I take this this work seriously. This is not just a job for me, this is superhero stuff,” he said. “And if we don’t change it, people can just continue to get shot. We can complain about this, we complain about that, but if we’re not going out here and doing nothing about it, it’s not going to change.”

Hayes started with Mastery out of college as a support teacher just six years before. He rose in the ranks fast. Coming into Wister, he was chosen by Jovan as a teacher leader and earned top salary on Mastery’s merit pay scale.

Jovan met Hayes through The Fellowship, an organization that he helps run which tries to recruit and celebrate black male educators. And for both men, Wister was more than a school; it was a civil rights opportunity, a chance to say, “Black lives matter,” and put the work into backing it up at the nearly all-black school.

“We got a child that just got shot 10 times,” said Hayes. “This is their reality. So they have to learn how to be themselves, but how to be a better version of themselves. So I have to show them and I’m still me. I’m still the guy that grew up in the ‘hood too, you know. But you got to learn how to code switch. There’s times you’re going to have to be in an interview and give eye contact. There’s times that you’re going to be asked to do something that you don’t like, but because it’s your job, you’ve got to learn to put on the elbow grease and get it done.”

Watching Bahir Hayes teach is like watching Steph Curry shoot three pointers. Like reading a beautifully constructed John Updike sentence. Like listening to Billie Holiday sing. The man flat-out has talent.

With an infectious smile, he commands a classroom’s attention. He pours his whole body, his whole personality into teaching, moving all around the room. Sometimes he comes across like an older brother teasing in the school yard, disarming students with an exuberant laugh.

And other times he’s the stern father emphasizing the long-term stakes for the work being done in the present. He frequently asks students, “Do you want a job? Would I hire you? Would I trust you?”

Nothing seems to please him more than when a student makes a thoughtful point while speaking clearly and confidently.

“Did you feel that?” he’d ask the class, “the way that she just commanded respect!”

I was in his classroom multiple times throughout the year, and when you watch the students, you can feel real learning happening, hear the buzz of ideas being exchanged.

When he calls for attention, he gets it immediately. And he simply doesn’t let students zone out.

“You’re not tricking me, bro,” he said to one boy who was closing his eyes. “It’s time to get to work.”

So what’s the secret to his success? To him, it starts with setting high expectations from the jump, and getting the kids to buy into a set of routines.

“It’s not about being strict. It’s not about being mean. Kids like to know what to do. Most of these kids are coming from chaos on a day-to-day basis,” he said. “They like coming here, knowing exactly what to look forward to because they don’t get that outside of here.”

For example, he demands that students keep their eyes on who ever is speaking. And he helps students find the language to agree and disagree in group discussions.

“It’s important that they understand how to do those things, but unless we teach them, it won’t get done,” he said in an interview early in the school year. “And it has to get done now because in December it’ll be too late. You can’t reteach things that kids are already doing. So if they pick up these bad habits and we don’t address it right now, in December it’s over with.”

Hayes’ talent lies in being able to get kids on board with this while not making it feel stiff or regimented. It’s all a baseline leading to something more authentic.

As an assistant principal, it’s Matt Rankin’s job to oversee teachers. And within the first few weeks of school he was blown away what what he was seeing during observations of Hayes.

“Kids were just making connections with each other. They’re like, ‘You know what, I disagree when you say that,’” said Rankin. “And I was like, ‘Hold on.’ I had to actually walk out in the hallway, like, ‘This is a turnaround school. That classroom feels like those kids have been in there all year.’ Felt like it was April. That was the first moment when I was like, ‘Wow.’”

The students feel it too.

Zakiya Ross told me her three favorite things about school are gym, recess and Hayes’ class.

“That’s the best teacher,” she said. “He’s funny, he teaches us stuff.”

Shikier Anas Richardson agreed.

“He’s strict, but he’s not really strict. He’ll be funny at the same time. But he always got his point across,” he said.

For Hayes, the point underlying everything is helping students develop the social, emotional and intellectual muscles they need to break cycles of incarceration and dependency.

“They are they are the foundation for the future. And if we educate and empower them, some of these things won’t happen again, because they don’t know how to talk. They’re going to know how to keep themselves out of situations. They’re gonna know how to speak to officers,” said Hayes. “They’re going to know how to start their own businesses.”

Seeing Hayes in action was a vast departure from the image some of Mastery’s detractors painted during the conversion debate — one of a school that would be militaristic in its obsession with standardized test results.

On the first day of school, Hayes laughed off that criticism.

“It’s not on my mind at all. Not thinking about that. Because if I do what I’m supposed to, that chart is going to go up regardless,” he said. “I don’t I don’t teach for the results. The results are a result of my teaching. Period. That’s just the mindset I have. if I’m doing what I’m supposed to, the results are going to be there.”

A work in progress

Directly across the hallway from Hayes sat the classroom of math teacher Nate Higgins. Burly and white, he grew up in the Philadelphia suburbs, played Division III football and started his career in financial planning.

“I hated it. I hated what I was doing,” said Higgins. “I started coaching football — 7th and 8th grade football, and it was awesome working with the kids and I said, ‘This is what I wanted to do.’ So I went back and got my master’s in education.”

This was Higgins’ second year as a teacher, but first with Mastery, and first in Philadelphia, and he came into the job excited to help revitalize the Wister community and put down roots as an educator.

“You hear it all the time. A lot of these students don’t have father figures,” he said. “So the ability to have an impact on a student and make a difference on their life is an awesome feeling. Hopefully this is the final stop.”

But despite how easy Hayes makes it look, this is extremely difficult work. And as is the case with many new to teaching, maybe especially to urban education, Higgins struggled early in the school year to control his classes, even as he tried to stay optimistic.

“As far as students, I expected them to be a challenge as far as being a little behind, but they’re getting up to speed and they’re eager to learn every day,” he said.

Being in both Hayes’ and Higgins’ classrooms was an eye-opening experience.

The same exact kids who with Hayes would be engaged and focused, would come across the hall and be chaotic. Students would sometimes move around the room freely, talking amongst themselves, throwing paper balls.

A few students would be trying to pay attention, but the majority were disconnected from the work.

“It’s, like, he’s a good teacher, but I feel like he can’t take care of a whole class at one time,” said student Naiome Roberts.

At one point a few months into the school year, I was in Higgins class with a videographer. And each time things got out of hand, he would ask us to stop recording in order to remind the class that they were being filmed.

In an interview later that day, Higgins reflected on the classroom dynamic.

“The one thing I preach is that we’re in this together. And if they get that sense of feeling that it’s not ‘me against them’ or me just up there to just do my job and collect a check. But if I say, like, ‘Hey, we’re in this together. We’re going to figure it out together. You’re not on your own,’ they’re more willing to work harder for you. And then it does become difficult. Some kids do want to act up and not do the work, but we have great support here.”

Compared to young teachers in many urban schools, who can feel alone on an island, Mastery truly did give Higgins a lot of support. He had deans to help with kids who were misbehaving. He got tips from a one-on-one teacher coach. Jovan would come by to help him, as would assistant principal Matt Rankin.

Rankin would come into his classroom and model for him in real time how to be more effective.

“Put your eyes on Mr. Higgins,” Rankin said to the students in the class one day. “He’s going to give you really clear directions. And I’m happy to have one-on-one conversations if there’s any confusion about those directions.”

Rankin later explained his process as “teaching the teacher.”

“Just giving him that feedback in the moment so that he learns on his feet, instead of me coming back to my office saying, ‘Here’s some feedback for you.’ And then him actually having no idea how to implement that,” he said.

For some this could be an unnerving experience, but Higgins took it all in stride.

“What helps me is that I’m a former athlete. So, I was always constantly in film rooms, and you know what Mr. Rankin and Mr. Weaver are saying to me is completely different and a lot nicer than anything any of my coaches ever said to me,” he said with a laugh. “So it’s better.”

Despite Higgins’ early struggles, Jovan held out hope that things would begin to rapidly improve.

“He has a great attitude, and it’s all about molding him. But he has to also want to be molded. We can give him all the feedback in the world, but he has to internalize that feedback and then on the back end execute it,” said Jovan. “He’s a work in progress.”

Insights

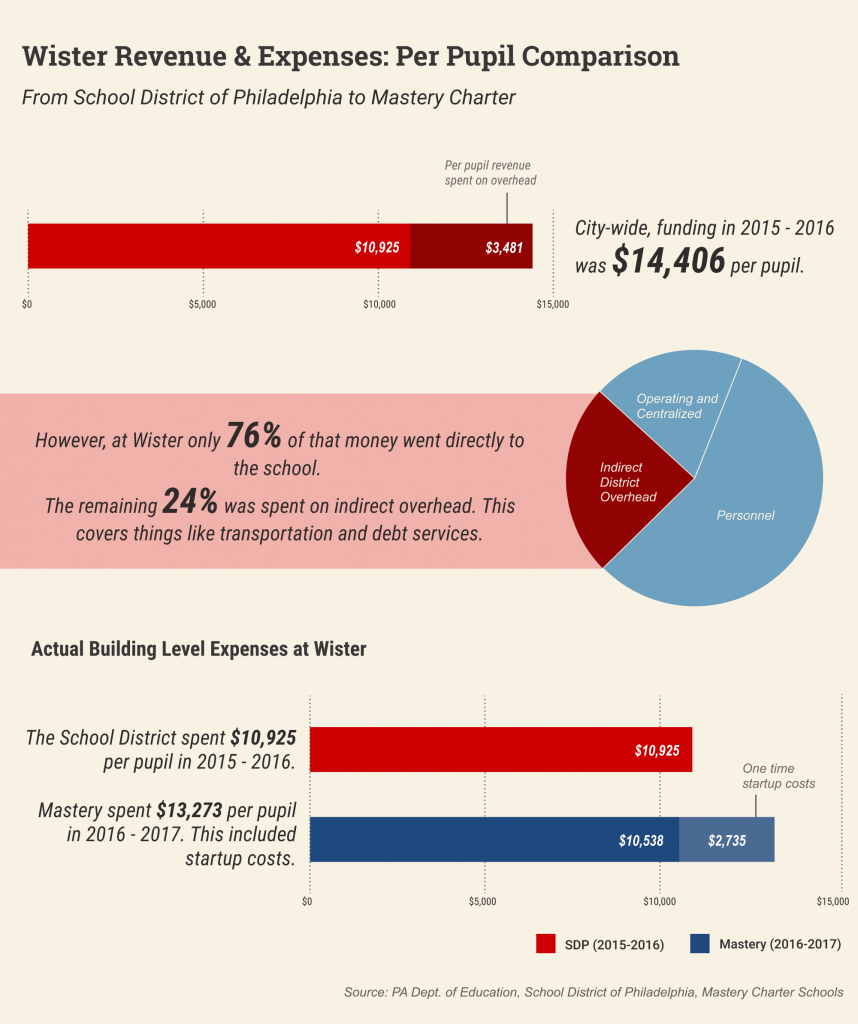

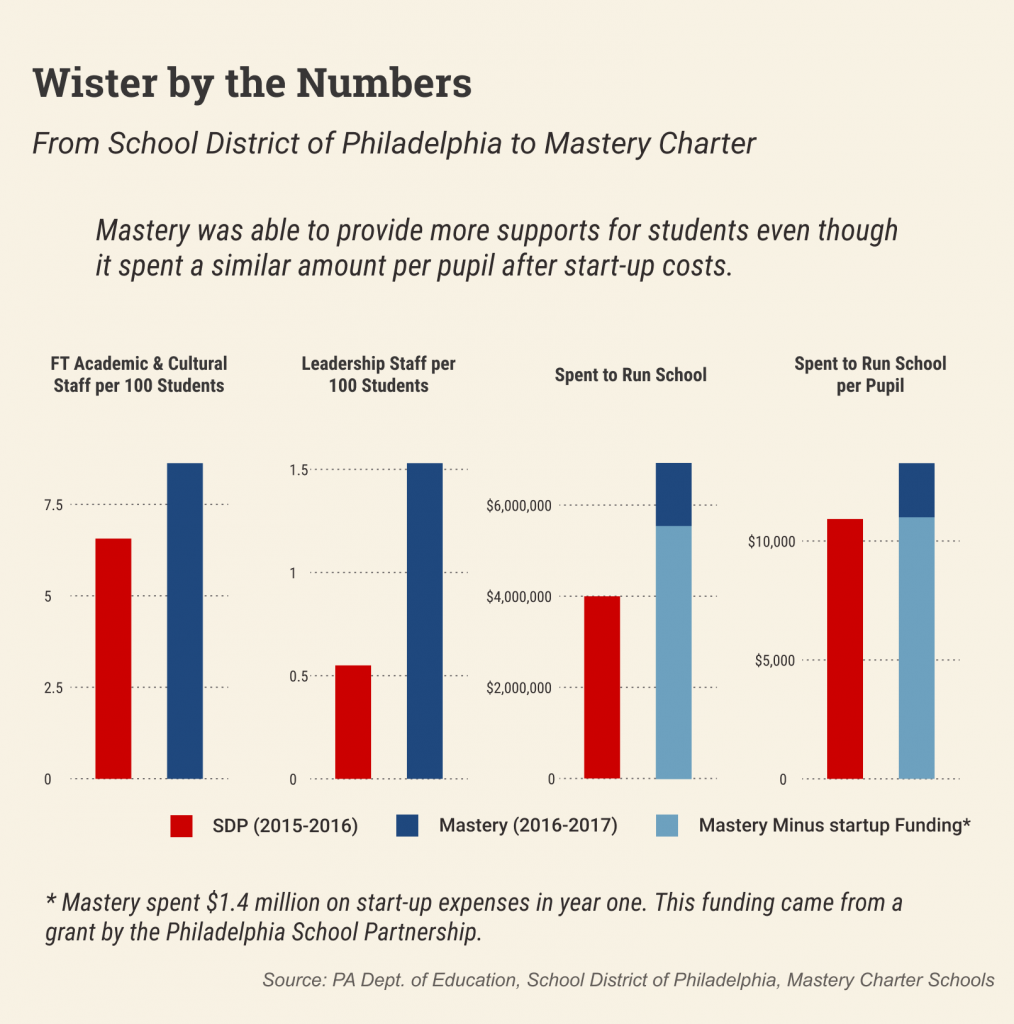

Examining the difference between how Wister operated under district control and under charter control, it can’t be overstated the role that added resources play.

All the supports that went into helping Mr. Higgins make this plain.

Truly understanding this, though, required digging deep into the finances and the staffing at the school both before and after the charter conversion.

A few stark takeaways emerged.

On a per pupil basis, Mastery had a significant edge when it came to full-time professional employees inside the school. Where the school district had a 1:15 full-time professional to student ratio, Mastery’s was 1:12.

The difference was especially pronounced when it came to leadership and support staff.

The district had one principal and a single guidance counselor, but Mastery had a principal, four assistant principals, a director of operations, two deans, a social worker and a community engagement manager.

At Mastery, for every 75 students, there was someone in leadership. Under district control, the ratio was more than double that.

The role this plays is immense. It allows Jovan to do things that his predecessor couldn’t dream of — dedicating staff to diffusing behavioral problems before they blow up, giving teachers like Higgins that real-time coaching, and forging better relationships with parents, to name just a few.

How’s it feel to parents?

“They’re more involved with the students. Before you didn’t really get that. It was like, they were just here,” said Lateefah El, a mother of a 5th grader. “You had some teachers that cared, because my daughter did have a lot of really good teachers. I’m not saying that they didn’t care, it’s just they wasn’t so involved.”

During the conversion debate, Wister’s former principal, Donna Smith, called for more staffing supports in testimony before the school board.

“I want to work with the same resources that I had in 2008: [aides] in all classes in K-3, enough noontime aides to adequately cover the lunchroom, money for yearlong, extended-day tutoring programs, money for extracurricular activities, parent ombudsman, school police,” she said. “These are things we had that made our school work. Leave our school public! I have a dream of public school success.”

But here’s where it gets tricky. When you analyze Mastery’s budget for Wister, and take away those start-up funds used to make the building nicer, you see something kind of shocking. Mastery actually spent almost exactly the same amount of money per pupil to run the school as the district did.

So it’s not really an influx of cash that’s buying these added supports.

So what is it? What’s the difference?

The answer to that question is nuanced, kinda wonkish, and was pretty much never straightforwardly explained to parents during the giant public debate that led to the school conversion.

This lack of clarity was voiced at community meeting in Germantown soon after the superintendent of the School District of Philadelphia proposed converting Wister into a charter school in October 2015.

“That’s confusing to me,” said one attendee. “Where was this money before? And why now all the sudden is it available?”

Top officials both at Mastery and the school district agree that the biggest factor here comes down to efficiency.

When Mastery took over Wister, enrollment shot up by 150 students. And Mastery very purposely has larger class sizes than many district schools in order to stretch dollars further, leaving more funds that can be spent on extra supports.

At Wister, each class had 26-29 students. In district schools with dwindling enrollment, class sizes can be significantly smaller than this. And this means a huge difference to a school’s budget. Mastery estimates that this factor alone allowed it to spend $1.5 million dollars more at Wister than the district could the previous year.

District officials could not confirm this exact number, but agreed, in general, that no matter who runs a school, as it becomes more popular — and attracts more families — great things happen for the bottom line.

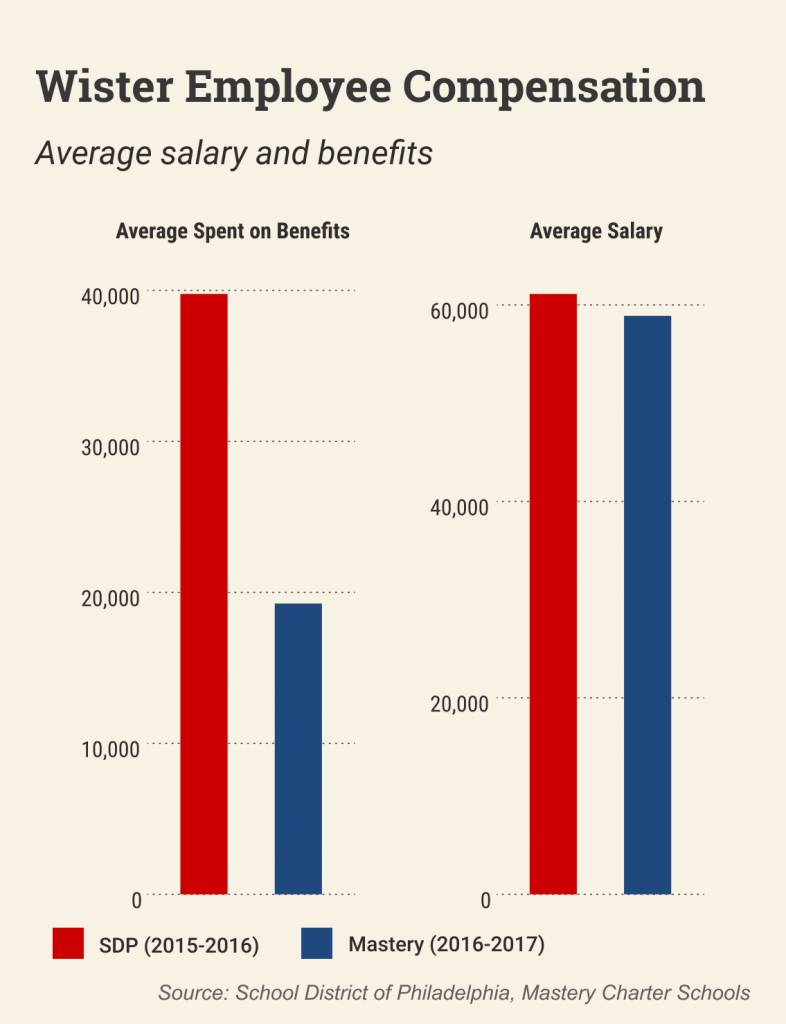

To a lesser extent, the difference in resources also comes down to how employees are compensated.

For one, Mastery’s teachers at Wister were much less experienced, and therefore skewed cheaper. According to state data, Wister’s teachers under district control had an average of about 14 years of experience. When Mastery came in, it brought a whole new staff and average teacher experience dropped to just two years.

Moneywise, this makes a difference, but employee retirement funding is an even bigger deal here.

Based on missteps by the state, the teacher pension fund in Pennsylvania is so unhealthy that school districts have been required to spend increasingly larger sums of money on it every year. In the last year the district operated Wister, it was required by the state to devote 26 percent of employee salary to the pension fund. The state later reimburses the district for a portion of that expense.

Charter schools have the luxury of opting out of that retirement system entirely. Mastery has done that, and uses a defined contribution retirement program with fewer long-term guarantees for employees. Using this system, Mastery spends only 9 percent of employee salary on retirement contributions.

All told, all these factors trickled down into real budgetary differences that had a clear impact on students at Wister.

In a conversation about these differences with Philadelphia City Councilwoman Helen Gym — a fierce critic of Mastery — she framed her response as an attack on the city school board, saying it should have fought harder for more funding when the school was run by the district.

“It knew what had to be done to provide a quality school education. It didn’t advocate enough at either the state or the city level to make that happen,” she said. “It continuously blamed public schools, teachers and students and families who came forward asking for investments and change.”

Gym’s reply resonates with many distressed school districts, who don’t believe funding is anywhere near adequate.

But it avoids the more immediate dynamic that’s happening here. Simply put, Mastery ran a much more financially efficient school. And the Wister community traded away more experienced, more expensive teachers who had more reliable retirement income, and, in exchange, they were able to provide students with much more support.

And these were the insights that were never made plain during the yearlong raucous debate.

No excuses

It was not uncommon to find Jovan Weaver quarterbacking a touch football game with students in the schoolyard before classes. Jovan would call, ‘Go!’ and you’d hear a smattering of kids yelling, “Mr. Weaver! Mr. Weaver, I’m open!”

It was all part of the tightrope Jovan walked as the school year progressed. He and the staff were strict and demanding with themselves and the students about academic improvement.

But Jovan also emphasized that Wister needed to be a hub of positivity and love.

“Look at their mindset. They’re happy,” he said after one of the morning games. “They’re energized. They’re ready to go in, they’re going to eat breakfast. It’s just starting their day off well.”

Everyday, Jovan celebrated students through daily morning announcements, and most mornings, he greeted every student with a high-five as they came into the school.

“I can see from the time they’re walking in what type of day most of my kids are going to have. Some kids are crying. I’m not just going to let you give me a high-five and walk past me as you’re crying. Step to the side, ‘What’s going on? Let’s have a great day…This is a place where you can be happy.”

A lot of the story with Wister has been about a comparison, about how things changed as the school transitioned from district to charter control.

But Wister’s story also speaks to a more universal and brutal truth: many, many students in our most impoverished schools are suffering in their home lives.

“I have children in shelters that are smart as hell, but it is tearing them apart, because everyday they know their mom has to wait for a spot because they don’t know where they’re going to stay. They don’t know they’re going to have a bed at night,” said Jovan, tearing up. “And, yet, they have to come in here and go through the motions of a school day. That is so difficult. We talk about no excuses, but you have a child who doesn’t know where they’re going to sleep at night. They don’t know. What do you mean there’s no excuses? You’ve got to be kidding me.”

For Jovan, who lived this himself, each day is an opportunity for the school to be a beacon, what could be one of the only good things a child has going for them in life.

“I’m so intentional on building their mindset and building their confidence because oftentimes, even if they have both of their parents — in some cases some parents are so far checked out that they don’t even notice how beautiful their children are, and how much their children are just growing and developing right in front of them,” he said.

This other brutal truth about parents can’t be ignored. In general, they are key allies a school needs to truly affect positive change, but in some cases, schools are left to help kids succeed despite the destructive behavior of parents. And many of them, like Jovan, are the sons and daughters of the crack epidemic.

“Overall the community has been great and has just received us and have been such a huge part of this transformation,” Jovan said. “But you still see it. You still have, you know, people come up to you that are clearly inebriated, like, they are drunk. They are just reeking of whatever Budweiser or whatever the hell they were drinking, and for whatever reason feel like they can have a conversation with their child’s principal while they’re in this state. There’s a disconnect there. But if you feel like you can have a conversation with me, I cannot imagine what’s happening in that household. And then you look at the child and you’re, like, ‘Wow, I need to pour little bit more into this child. I’m going to give this child a little bit extra now. Everytime I see this child I’m going to make sure I stop and we’re going to have a conversation just so they know that there’s more out there.’”

Jovan was particularly affected by one interaction with a parent who was reeking of marijuana when he came to pick up his six year old child.

“It’s so ignorant and they don’t understand. But when that child gets older, man it’s going to blow their mind, because they’re going to be like, ‘What? This is what was happening?’ What are you doing? You’re just perpetuating the same cycle. You’re perpetuating the same habits. You’re perpetuating the same diseases, and it’s insane,” he said.

Soon enough, the evidence of how all this affects student learning became clear.

Early in the year, Jovan reviewed benchmark data showing deep academic deficits starting in the early grades. Seventy percent of the first-graders were considered “pre-primer,” meaning they struggled to identify letters.

“It shows that last year — given all the turmoil — it was almost a wasted instructional year for our students,” said Jovan, “and that’s unfortunate.”

The story of the fifth grade continued to be a tale of two sides of the hallway. By November, english teacher Bahir Hayes the social studies teacher were seeing clear progress in students.

“They’re exceeding my expectations at this point to be honest with you,” said Hayes. “They really are. And I’m really proud of that.”

Nate Higgins continued to stay upbeat.

“They’re lively,” he said. “Our class is a lively bunch and it’s a lot of fun though.”

But by Thanksgiving, as Jovan pored over the data, the pressure on Higgins began to mount.

More benchmark data found that students in grades three through five were struggling with math as much or more as they had been when the school was under district control.

Meaning, even with all the added support, to that point Mastery wasn’t living up to academic expectations, and wasn’t really coming through on the idea of true transformation promised to parents.

And to Jovan and assistant principal Matt Rankin, it began to feel like they were falling short of their goals.

“I need to be able to look at something that says to me that we made a difference for kids,” said Rankin. “At the end of the day, for me, it’s all about: did kids make significant growth?”

Mastery’s central office was also well aware of the issue and pressing for action.

Based on this data, things across the building started to change. The plan for each grade was altered on the fly in hopes of improvements.

“We’ve completely revamped the curriculum,” said Rankin. “We have to nail that before we can move forward.”

Jovan, who started his career as a math teacher, added to his day-to-day duties and took over teaching the fourth grade classes, replacing another struggling teacher.

But the question of fifth grade was more difficult.

And by December, it started to look like something drastic would need to happen with Mr. Higgins.

“If you leave somebody in a role where they’re not successful, at the end of the day it impacts children,” said Rankin. “And we just don’t believe that that is ok.”

—

Continue reading in part 4

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.