Battle lines: The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary School — part two

The debate that led to Wister’s conversion to a charter school raised questions of politics, access and influence. And it pitted Philadelphia neighbors against one another.

In his first public act as principal of Wister Elementary, Jovan Weaver did something a little unconventional.

The school is in Philadelphia’s East Germantown neighborhood, known for pockets of deep poverty and struggles with violence.

And the first-year leader wanted to set a tone early that parents should think of the school as a homebase for the community.

So, he threw a big party.

On a hot August day in 2016, the schoolyard was hopping with parents, students and teachers. Music blared from DJ speakers. Big barrel grills cooked racks of meat over burning charcoal.

And Jovan took it all in — looking out over a student body nearly entirely African American.

“I see myself in every black boy that I see. I see myself in every black girl that I see,” he said.

Jovan’s own two young children, Jace and Ariel, were there too. And his goal with this party, and the year in general, was to make Wister everything he’d want his own kids’ school to be — and to get it to the point that he’d want to send them there as well.

“I’m a parent. I walk into Jace’s school and Ariel’s school all the time and they’re fully transparent, and there’s a bunch of communication. That’s the same thing that I want my families to experience,” he said.

Coming into this new school year, the expectations were immense. The idea was for a brand new team of teachers and leaders to make a dramatic difference in the lives of the students in this neighborhood, to increase their learning abilities in ways that would alter the course of their lives.

William Jackson, parent of an incoming kindergartner, had bought into that promise, and so far was encouraged.

“For this community, just having these kids out here, just around and having fun, was dangerous,” Jackson said that day as his daughter ran circles around him. “To come back here and have the families and have such a great day. This is a statement.”

But getting to this point was no small matter. In fact, the entire process that led to this moment was part of one of the most contentious and controversial school policy debates that Philadelphia has ever seen, one that came to epitomize the confusion, the politics, and the fury that have long underlied the school choice debate — not just in Philadelphia, but across the country.

The story of Jovan Weaver and Wister Elementary can also be experienced as a radio documentary. The tale is told across the four-episode second season of our podcast “Schooled.” It’s based on more than two years of reporting about the students, the parents, the faculty, and the huge political fight that sprung from Wister Elementary. You can listen using the play button above. This is part two.

Battle lines

So why did this debate, about Wister, surge to the forefront?

To answer that, we have to leave Jovan Weaver for a bit, and rewind about 10 months back from that community barbeque to a press conference in October 2015.

As part of a larger initiative to spur change in the city, William Hite, the superintendent of schools in Philadelphia, told reporters he wanted to give control of three city elementary schools to charter operators.

“These schools have been chronically underperforming for many years,” said Hite.

Each had very low scores on state standardized tests, and more and more parents from those neighborhoods were sending their kids elsewhere.

One of the schools was John Wister Elementary, where 2014-15 data showed that only three percent of students were proficient in math and 19 percent were proficient in English. The school’s K-5 enrollment had grown steadily from 2008 to 2013, but then declined by about 40 students leading into Hite’s decision.

“There’s a level of urgency around making sure that these families have access to quality programs,” he said.

What Hite was essentially saying here was: the district has been doing such a poor job at this school, that we think somebody else can do it better. It’ll still be a public school, but we as the traditional district want to hand the keys to somebody else. In Philadelphia, this process is known as “renaissance.”

In the long history of public education, this is a relatively new idea, but it gets to the heart of what’s at stake as public schools have evolved over the past few decades.

Typically, when a proposal like this is made, there is an immediate shock factor, especially for the existing school faculty who are being called on the carpet in a very public and shaming way.

“I’m very much overwhelmed and I’m angry,” said Donna Smith, who was Wister’s longtime principal. “We’ve done a lot of work here, and I think the information that comes out on the news stations doesn’t paint the entire picture.”

Smith found out about the conversion proposal the same morning that the media did, and was still stinging from the announcement a few days later.

“I was walking out of the office this morning and one of my little preschoolers came running up, “Hey!” and he just jumped into my arms,” she said. “That brings you back for a moment, but that empty, kicked in the gut feeling — no matter how much you try to just bury yourself in the kids or bury yourself in the work, that reality comes back again.”

Wister’s staff learned that day that the district was moving two teachers out of the building due to dwindling enrollment.

And to a faculty already feeling under-resourced, there was bitter irony in losing teachers at the same time as being told they weren’t doing a good enough job.

Staffing cuts were nothing new to teacher Melissa Rasper. She’d been at the school 11 years at that point, and saw resource levels rise and then sharply fall through years of a district budget crunch.

“We make it happen here regardless of the cuts,” said Rasper. “So that’s why I feel like to go back to saying that we are failing kids is just a horrible statement to make.”

Teacher Liz Healey felt disrespected by Hite’s decision after she had poured so much time and money into the school.

“I bought socks this weekend because I have children coming to school with no socks. I buy that. They don’t give that to me,” she said. “I have no math books, no reading books, no work books. Everything has to be copied and that copy paper comes out of my pocket, not theirs. And yet they hold us to the standard of the suburban schools. I have friends in the suburban schools who are getting iPads. I don’t have a math book.”

The news of a big school change can also take parents by surprise.

Imagine suddenly being told your kid is in a “failing” school. You may have known it had problems, but not “failing.” The district’s central office apparently did know, though, and now its answer is to turn the job over to some other unknown entity. And that unknown can be scary.

Anger in Germantown

Shortly after Hite’s announcement, the district held a parent meeting at a Germantown community center to talk things through. It was a volatile scene.

“Ya’ll not sitting there trying to help us. Ya’ll want to do what ya’ll want to do,” yelled one parent.

There were false rumors.

“We want to know why are you all taking pre-K and kindergarten off the school when you say, ‘no child is left behind?’” asked another parent.

There was fondness expressed for the school’s existing faculty and general cynicism that the district’s central office had children’s best interests at heart.

“My child is not suffering — my oldest, nor my second son,” said another mother. “They’re not suffering. They’re not. They’re straight ‘A’ students. They’re good kids. They know these people love them. You guys are giving us this information, [that] information, so now we don’t trust you. So how’s our children supposed to trust you?”

But there was also criticism of how the school was being run, like from grandparent Ed Lloyd.

“Teachers being absent most of the year. My one granddaughter had multiple teachers all year long — substitutes all year long, all year long,” said Lloyd.

Uniting both sides was disgust at the way the process was being handled. The last time Superintendent Hite had made a similar proposal, parents at other schools were given a chance to vote. They could either choose to have the school stay under district control or become a charter.

In those cases, parents overwhelmingly voted against the conversion, but this time, Hite decided there would be no vote.

The rationale behind that procedural change gets at a one of the big reasons why these proposals can escalate into massive fights.

When a charter school takes over, it’s a threat to the teachers union. Most charters don’t have unions and teachers work on year-to-year contracts. So the more charters there are, the more erosion there is of the job protections and benefits that collective bargaining has given public educators.

And that’s something union members present and past devote a lot of time and energy fighting against — people like retired teacher Karel Kilimnik, who came to that Wister parents meeting too.

“You can hear these salespeople up here. They’re all pushing corporate education reform on you in the name of renaissance charter schools, but you have a voice,” she told the crowd. “There’s a lot of anger, there’s a lot of frustration. There’s a lot of real street smarts. You gotta use what you have to fight for what’s important for you and your kids.”

And so when Hite stripped away the vote, the implication was that the parents had only shot down his proposal the last time because the union had organized and turned parents against their own best interests.

But, to the parents, it’s hard not to read that switch as: we don’t think you can decide what’s best for your kids.

“When was our time to vote?” asked parent Kenya Nation Holmes, at that meeting.

When Evelyn Sample-Oates, a central office staffer, responded, “That’s not the process this year,” parents gave her an uproarious earful.

Two sides

When these sort of charter conversion proposals get made, battle lines are drawn around familiar quarters. The union and its supporters in politics and academia line up on one side.

And school choice advocates and their philanthropic and political backers line up on the other.

Both organize in what becomes like a political campaign to win the hearts and minds of parents, who are often caught in the middle.

If you’re a parent against the change, you’re labeled a puppet of the union.

If you’re a parent for it, you’re being manipulated by the deep pockets of the school reformers.

With Wister, this debate could largely be boiled down to two women with deep ideological differences. Both started as community advocates, and then rose to positions of power and influence.

On one side: Sylvia Simms, a grandparent from a poor Philadelphia neighborhood.

“A lot of people don’t know me. They have a perspective of me. They have what somebody else told them about me, but they don’t know Sylvia P. Simms,” she said.

For years, Simms worked for the school district as a bus attendant, and then became a parent organizer and an advocate for school choice. She was appointed to the city’s five member School Reform Commission — essentially the school board — in 2013.

And, the way she saw it, she was there to represent low-income parents.

“These are my families. These are my children, because I’m there with them. I live like they live for the most part,” she said. “I am their sister in the struggle, and the struggle is real.”

Simms was all-in for the change at Wister from the get-go. She says the needs of students in Philadelphia are so great, and require such urgency, that all the old rules need to be thrown out the window, with little sympathy for how that affects anyone but poor children.

“We have a lot of failing schools, and I really think that we are not moving fast enough to try to change.”

On the other side: Helen Gym, a parent and teacher turned journalist who became a persistent, nationally-recognized advocate for public schools.

“There is no way that we can disinvest in public ed, and then look at declining outcomes and blame the schools in those communities for it, and use that as an excuse to privatize them,” she said.

Gym was elected to Philadelphia City Council with robust support from the teachers union in 2015. And to her, charter school conversions and supporters like Simms embody an abdication of the school board’s responsibility.

“People who are completely stumped when faced with one of the most basic questions: ‘How do you improve a public school?’ They had no answers to give us. They only said, ‘I’ll hire somebody else to do my job.’ That’s it. That’s what they were giving us a choice over.”

The tension between these two ideologies makes a powder keg, one that explodes at jam-packed, marathon-length school board meetings.

“Public education was founded on principles of common good and not corporate greed. But our public school system is being systematically destroyed by the very officials entrusted with its care,” testified retired Philly teacher Diane Payne at the meeting two weeks after the proposal was announced.

“Schools are not failing, society, government, politicians and school district officials are failing. How dare you label schools as failing when you starve them of resources?” she said.

Later that night, Superintendent Hite singled out Payne in his closing remarks.

“It’s really important to ask the question, ‘Why at the schools that are serving minority children we haven’t been able to determine or figure out how to teach them to read or do math?’” said Hite. “And these children were not performing even when we had the resources many of you, especially you Ms. Payne, were describing that we had in schools.”

A difference?

Hite’s point gets into one of the most difficult things to confront in public education. Across the country, we’re not very good at educating students in deep poverty, especially children of color.

And when we talk about “good schools” we’re usually talking about ones that have in some way reduced their number of really needy children.

This happens in a number of ways: by drawing district boundary lines around communities of wealth; through limited-admission magnet schools; and it can happen in typical charter schools, ones where parents need to have the wherewithal to enter a lottery, and the school has more leeway to push out students who misbehave or don’t do well.

But this isn’t the arrangement that was proposed at Wister.

There, the idea was: same school building, same neighborhood boundaries, different people running the school.

And that’s a really tough ask. So tough, it sometimes fails miserably.

“Even with all the resources here, nothing is being accomplished. Nothing,” said Shereda Cromwell, a North Philadelphia parent who learned this lesson the hard way.

Her kids’ school, Kenderton Elementary, went through that sort of conversion a few years before the debate about Wister. Things seemed to go well at first, but then a charter organization called Scholar Academies abandoned the school without warning when the job got too hard and too expensive.

“They didn’t look at our children as people,” said Cromwell. “They looked at our children as dollars and cents. And it didn’t make any sense to them to invest any more money in our kids.”

Philadelphia has done these charter conversions more than 20 times in the past decade or so, and the results are pretty mixed. Sometimes, it seems the new regime is better. Sometimes better, but only compared to a low baseline academically. Sometimes it seems no different, or worse.

This type of true neighborhood-based work is so tough, that most charter organizations don’t seem to even want to try. When the district invited proposals to run Wister, it got only one reply — and that was from Mastery Charter Schools.

“Mastery is a kids agenda. We believe every child can succeed. This is really about growing our youth and building our city,” said Mastery C.E.O. Scott Gordon.

Mastery is the largest charter network in Philadelphia, and for a while looked to be head and shoulders above the rest when it came to taking on this neighborhood-based work.

But a new, more difficult state test brought Mastery’s results more in line with the city’s other struggling schools. And so, with Wister, the big question was: would a change in school leadership really make a difference?

The process

So far in this part of the story there have been a few references linking the idea of a charter school conversion to something seemingly financially crooked.

Both came from retired traditional school teachers. So what did they mean?

When you’re talking about control of public education, you’re talking about control of large sums of money. Money that goes for salaries, benefits, contracts. In Philadelphia, for instance, the district spends about $3 billion dollars annually on the more than 200,000 public school students in the city — both district and charter. About $900 million of that goes directly to the city’s charter schools.

And some people — especially union supporters — are very skeptical of giving those funds and that control to any entity outside of the traditional system, questioning their true motivations.

With charter schools, since there’s so many individual entities, it can be harder to have robust oversight of how money is spent, and there have been plenty of examples of misuse.

But there are also plenty of examples of impropriety and abuse within traditional districts.

And so charter supporters say better oversight is needed in general, and the answer isn’t to give monopoly of control to just one sector.

But, financially, there’s another idea to consider that motivates charter skeptics. Any time a district creates or expands a charter school, there are inefficiencies that end up negatively affecting the kids who remain in the traditional system.

So every new charter seat can be seen as a threat to the viability of district schools — ultimately leading to school closures.

“Dollars that go to charters come out of public school students experiences,” said Councilwoman Gym. “That’s not sustainable. Period. No matter what the outcome is going to be.”

But to charter supporters, this sounds too much like fighting to defend a system, not students.

“I see a lot of people fighting and standing up for the status quo,” said Sylvia Simms. “We’re really doing a disservice to a lot of these children in Philadelphia. But I don’t see nobody coming out fighting or screaming or being angry about that.”

So far, the debate around the Wister conversion has unfolded like similar proposals like it in the past. But in early January 2016, things took an unexpected turn — one that triggered a series of events that are still being debated to this day.

Depending on your viewpoint, what occured next either signals a corrupt, unethical travesty of big-money influence and political pressure, or a victory for low-income students and parents who were desperate for change and became empowered to make their voices heard.

Here’s what happened:

Superintendent William Hite announced that more up-to-date test data showed signs of academic growth at Wister, and so he decided it wouldn’t be fair to go through with his original conversion proposal.

“Because we only have finite resources, we felt that there are schools that are lower-performing than Wister that would need this level of investment,” said Hite in a telephone interview at the time.

But by that point, a vocal, organized collection of parents in East Germantown had become very attached to the idea of the Mastery conversion. That included grandparent Anna Figueroa, who, initially, was very much against the charter proposal.

“I was, like, ‘No, like, we need to keep in a district school. We need to come together and make a difference and make the school district accountable,” she said.

Figueroa really liked some of Wister’s teachers. And those hoping to keep the school under district control were hoping to count on her as an ally.

But she wasn’t ready to commit.

“They were saying, ‘Well, Miss Figueroa, can you talk at the SRC?’ And I was like, ‘I’m gonna hold off for a minute. I need to know more,’” she said.

Figueroa is a friend of both Sylvia Simms and Quibila Divine, who is Simms’ sister. Divine had worked for the school district in the 2000s, doing parent outreach under former city schools superintendent Arlene Ackerman. In that era, Divine trained a number of parents, including Simms and Figueroa, how to be advocates for school improvement and how to navigate Philadelphia’s school choice system.

As Figueroa was mulling which side to join in the Wister conversion debate, she asked for Divine’s advice and invited her to speak at a local parents meeting.

At the time, Divine was employed as a contractor with a pro-school choice consultancy firm that had worked for Mastery in the past.

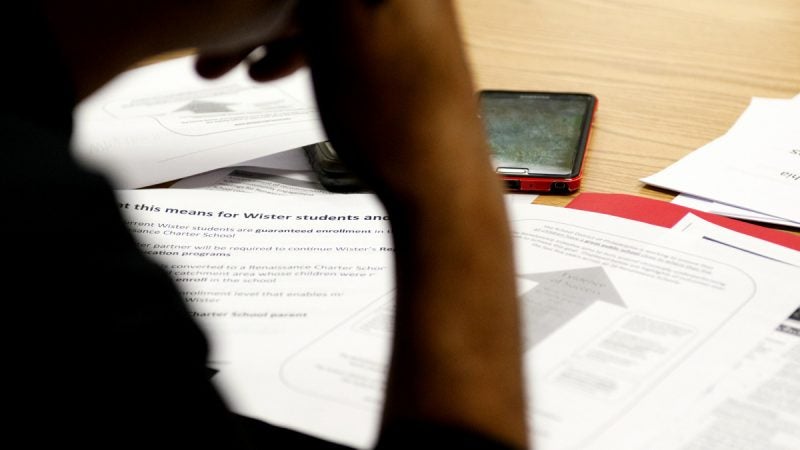

Divine agreed to speak to parents and showed them a powerpoint presentation.

“Pretty much what I told them is that there’s a whole lot of stuff, there’s a whole lot of information that you’re going to hear. You have to make the decision about what’s right for your child,” said Divine in a recent interview. “I’m not pro-Mastery. I’m not pro-charter, and I’m not anti-district. I’m pro-high quality education for all children.”

Figueroa was still on the fence about the proposal. She decided to tour one of Mastery’s other schools, Cleveland Elementary, which Figueroa had actually attended as a kid long before the charter existed.

“When I went to Cleveland it was like, ‘Wow, that’s my alma mater.’ I graduated from Cleveland. [I saw] two teachers in the classroom. The school looked bright. But also in the back of my mind, ‘Oh yeah, we’re taking a tour, they’re just like the district, they make everything beautiful, you know….’ but then I sat down and they had like videos of Oprah Winfrey donating to them, Obama was [praising Mastery], and then the kids themselves came in and spoke to us. And I was like, ‘Wow, this can be Wister.’ And that’s what made me change my mind.”

Other parents had similar experiences on tours, and they came out in force to testify for the conversion at the January 2016 school board meeting.

Alicia Grant, parent of a Wister second grader, questioned why Hite would rescind his recommendation without having a better alternative in mind.

Mastery had informed parents that if the conversion went through, the school would benefit from a $1.5 million dollar upgrade based on a grant it already secured from the Philadelphia School Partnership, a well-endowed pro-school choice philanthropic organization that aims to help low-income students.

“Mastery has their plan on the table,” yelled Grant. “The school board does not. They do not. I personally asked, ‘Can you match anything that Mastery is offering right now in writing that I have?’ They cannot.”

After months of being told how bad Wister was, parents like Sayid Parker felt betrayed by Hite’s flip-flop.

“Right now, what credit can I give ya’ll? Nothing,” said Parker.

Getting parents excited about Mastery and then angry with Hite’s decision was no accident. It was part of an effective community-organizing campaign by Mastery that drummed up enough grassroots support in East Germantown to create a wave of momentum.

When people like Figueroa became convinced of Mastery’s superiority, they spread the word like wildfire.

“‘When I was against it, I didn’t know what I didn’t know,’” Figueroa would tell other parents.

But money clearly played a role in garnering support for the charter too.

From public filings, we know that Mastery spent about $55,000 to lobby parents. An organizer was paid to advocate, others were hired to canvass the neighborhood, t-shirts were made, transportation to take parents on tours and to school board meetings was arranged, and Pro-Mastery videos were produced by a downtown public relations firm and promoted on social media.

To Mastery, this was about spreading the word of its mission and its work. The teachers’ union was trying to do the same.

But to Mastery’s detractors, its actions smacked of buying influence.

The exact details of the lobbying effort didn’t come to light until months later, after the city ethics board fined Mastery $2,000 for not disclosing the activity.

“Undisclosed lobbying is desperately unfair to the public process,” said Councilwoman Gym. “And it took a formal complaint with the city ethics board to unpack the lobbying that was going on at the time, but it had a role to play, and we can’t be naive about those kinds of things.”

Mastery calls the disclosure violation a “technical oversight,” and defends the need to get to know a community and educate parents about their options. The district’s rules for the school conversion process specifically ask potential charter operators to reach out to parents.

“Yes, there’s expenses involved,” said Mastery C.E.O. Scott Gordon. “We’re not permitted to be in the school everyday, so we go to the neighborhood and introduce ourselves and ask them: ‘What does the community need?’ And listen to parents, ‘What’s the most important thing?’ It’s a whole engagement process.”

Whichever way you look at it, in this case, the point is this: it worked.

At that January 2016 school board meeting, parents like Dionne Garrison-Hubert came to testify extremely invested emotionally.

“I have tried for years to get my children out of Wister and have been unsuccessful,” she said. “The only ray of hope that I had was when Mastery came around. They didn’t approach me. I approached them because they are the only option that I see for my children to have a fighting chance.”

This all happened at the meeting where the five-member school board had been set to vote on whether to advance the Wister proposal. But since Hite rescinded it, there was no formal resolution on the table.

During an especially contentious moment in the meeting, advocates for and against the change got into a shouting match.

It started with a “Turn Wister Around” chant from Mastery supporters. And then a response from a woman against the change yelling, “Give them back the resources” and “Don’t sell our babies.”

Wister parent David Childs, who had a first grader at the school, was for the change, and directed his testimony to naysayers in the audience, sparring with them loudly.

“Not only am I a parent, I’m a concerned father. You’re all screaming, ‘Give back the resources.’ There are no resources!” he yelled. “Mastery has the answer now. We have the solution now. My child deserves better. My child is in a failing school. The school’s been failing. This isn’t the start. This isn’t anything new. And for y’all? Y’all don’t even live in my community. Y’all don’t know what’s goes on with my kids. I see what goes on. Ya’ll don’t be in our meetings. So don’t talk about something that ya’ll don’t know.”

As this tension boiled, a little later in the night, in a surprise move, one of the school board members did something that caught most of the room off-guard.

That person: North Philly grandparent Sylvia Simms.

“I have a motion on the floor. I want to be clear that I am fully supportive of Dr. Hite’s leadership,” she said, her voice quaking.

Simms and another board member, Bill Green, had been visited by pro-Mastery parents in the days leading up to the meeting. And she says she was moved by their pleas.

“On behalf of the families who visit me in tears and I must say it again — tears in their eyes because they felt betrayed by the district — I must act today,” said Simms.

Simms then introduced a resolution to revive the idea of conversion.

To the parents who came to support Mastery that night it was a vindication, with a large section of the audience cheering.

Others felt betrayed. Parent Kenya Nation Holmes did not attend the meeting that night, thinking Hite’s reversal had put the matter to bed. Holmes had gone on those same school tours that Figueroa had — and really liked what she saw — but says teachers at Wister helped convinced her to oppose Mastery.

She feared the lack of teacher tenure would force educators to be too worried about standardized tests.

“So now I have to teach the children to take tests and pass with As or else I no longer have a job? You can’t teach like that,” said Holmes. “Where’s the passion? Where’s the love?”

Other critics say the whole thing was too wrapped up in back-door influence. Officials from the Philadelphia School Partnership had also lobbied school board members on the issue behind the scenes. And there were also conflict of interest accusations leveled against Simms.

This came up in the room that night, when a pastor from West Philadelphia stood up and began shouting as Simms cast the decisive vote advancing her action on Wister.

“You should have recused yourself,” screamed Pamela Williams. “It’s wrong. It’s wrong. Your sister got a contract. It’s wrong Sylvia, and I’m standing up for these parents.”

Williams objected to the fact that Quibila Divine spoke to Wister parents like Anna Figueroa while being employed by Citizen Consulting Group.

“One sister had the contract, then the other sister sitting on the board and gets the decisive vote. That’s wrong,” she said. “That’s just wrong.”

Quibila Divine says her consultancy job had nothing to do with Mastery or Wister, and that she didn’t stand to profit from the conversion.

“No contract, no money and there was nothing. And I was doing Anna a favor,” she said.

Later, both Simms and her sister were cleared of any ethical violations by both the district and the state ethics board.

Still, Philadelphia’s mayor blasted the board’s move that night, as did the city council president.

Councilwoman Helen Gym was in the room when it happened.

“I find walk on resolutions which are not vetted, did not allow public testimony, and did not allow for any public discussion to be completely untoward in governance,” she said in an interview shortly after the vote.

At the end of the night, Superintendent Hite expressed disappointment the board went against his recommendation, but sympathized with its rationale.

“This was a lot to deal with,” he said. “This was a tough and emotional piece.”

Simms says the whole ordeal was blown out of proportion by people who had nothing directly at stake in the matter. She says she only acted in the interest of parents.

“They came to me seeking help. So I had to be their voice,” she said. “And that’s why I did what I did, because I am fighting for the families that can’t fight for themselves. I am the voice for the voiceless.”

‘Dig yourself’

Following that surprise vote, Wister dominated news headlines and editorials, and in East Germantown, neighbors were turned against neighbors.

Wister parent Dionne Garrison-Hubert, who we heard testify for the change, was criticized by a popular morning host on Philly’s black community radio station.

“Solomon Jones called me a sellout. He said, ‘Oh, so you sell your kids out?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely. I sold out for a better product,” she said.

Other Mastery supporters say their kids were picked on by the district school staff. Anna Figueroa says her grandkids were singled out when Superintendent Hite rescinded his proposal.

“My grandkids came home and said, ‘Mommom, Ms. Smith and the teachers said they beat you up. They won. You’re a loser.’ I’m, like, ‘What? Why are you picking at my grandkids? They kids,’” she said.

Kenya Nation Holmes, who was against the change, felt bullied by Mastery supporters.

“The last SRC meeting I went to, I was being taunted by them in the back. They were calling me names. They were saying things under their breath as I’m trying to read my speech. Towards the end it was very childish,” she said.

Feeling all this pressure, the whole process just became too much for Wister grandparent Gail Tarver.

“The tactics used against the families of the Wister Elementary school have been damaging and divisive,” she testified at a later SRC meeting. “And I think that the SRC and the way you conduct your turnaround business, you guys need to dig yourself because you’re hurting these kids.”

The final decision on the change at Wister didn’t occur until late April of that year. In the weeks preceding, opponents made one last push to stop it, with the rhetoric against Mastery reaching fever pitch.

At a big rally outside district headquarters in March, Minister Rodney Muhammad, the president of the Philadelphia chapter of the NAACP, spoke of the school board and Mastery in reference to the slave trade.

“They are nothing but consultant group for private industry who want to takeover our children and put them back on the auction block,” he yelled. “Are you with us to shut this down?”

During public testimony later, Wister phys-ed teacher Robin Lowry predicted tragic outcomes for students if the transition went through.

“Wherever characterizations occur — Chicago, Philly and L.A. — we will see increased gang association and youth disenfranchisement, because most of our vulnerable students will have been kept in schools with limited choices and a cold, controlling environment,” said Lowry.

And so the question is: was this all the bluster of union supporters afraid of change? Wisdom based on the spotty record of past conversions? Some combination of the two?

Kirby Ames, a high school senior at another Mastery school, saw it as the former.

“I’m graduating this year. Mastery gave me a lot, and I’m thankful for it,” he said. “I don’t believe any of the stuff they’re talking about up there.”

On the night of the final vote, the board approved the conversion in a 3-1 decision. The voices of the skeptics were drowned out, and only time would prove them right or wrong.

‘Part of the cost’

Mastery was awarded a multi-million dollar contract to run the school. And the existing faculty at Wister would lose their jobs.

And for Mastery’s staff, it was time to get to work, time to prove that this whole idea was worth it. To prove that all the drama, all the tension, all the time and energy and emotional investment from parents would not be for naught.

And the person they had in mind to take this responsibility on? To lead it?

Jovan Weaver.

“I remember sitting down while watching the decision that night,” said Jovan. “I was cheering right along with parents, like, ‘Yes, yes, yes.’ And I was just as excited as they were.”

But, personally, things were about to get a whole lot more difficult for Jovan.

As an assistant principal, being a workaholic had put a strain on his relationship with his wife, and a week after he formally accepted the Wister job — which would mean even longer, more intense hours — they split up.

“I put everything else first, put my kids first. I put working and all that, but I’m thinking that everything I’m doing is showing you that I’m putting our family first. I’m working hard so we can buy a new house and we can have a great life. But her. I could have took care of her more,” Jovan said, fighting back tears. “I was not a good husband. I wasn’t. And I can say that now, and I’m sorry. I apologized to her.”

And so as Mastery took over Wister, and Jovan planned what the change would mean for the students and parents of East Germantown, he did it with a heavy heart.

But he did it with more determination than ever.

“I chose a life that would impact other lives,” he said. “And maybe this is part of the cost for that.”

—

Continue reading in part 3

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.