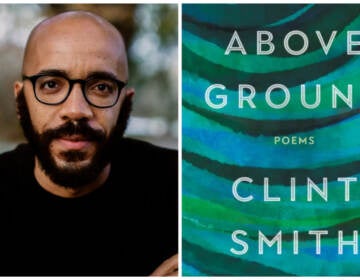

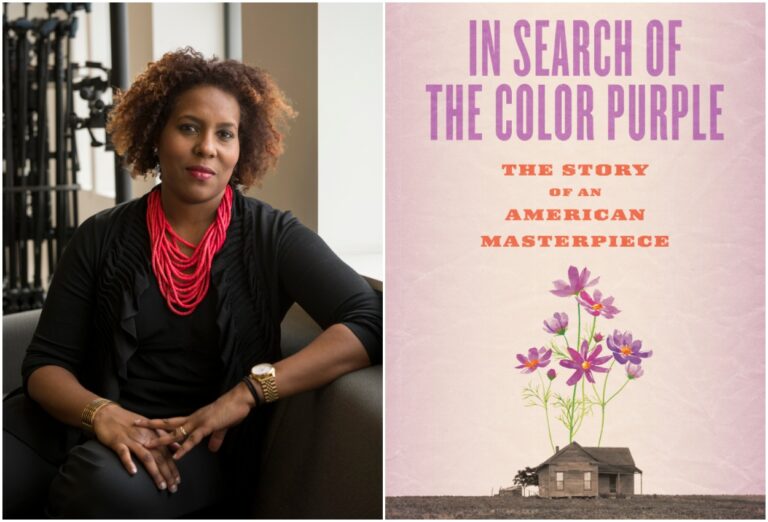

“In Search of The Color Purple”

Salamishah Tillet on the power of Alice Walker's 1982 iconic novel, how its lessons continue to resonate today, and how she's found healing in its pages.

Listen 49:26

SALAMISHAH TILLET first read Alice Walker’s 1982 Pulitzer and National Book award-winning novel The Color Purple when she was 15. The powerful story of three Black women, Celie, Shug and Sofia, surviving in rural Georgia in the early 20th century while confronting domestic violence, sexual violence and white racial oppression helped awaken feelings of racial pride and Black feminism in her. Over the years, Tillet has revisited Walker’s seminal book many times and as a rape and sexual assault survivor has found strength and healing in its portrait of sisterhood. This hour, Salamishah Tillet, professor at Rutgers and New York Times critic-at-large, joins us to talk about her new book, In Search of the Color Purple: The Story of an American Masterpiece. It’s about her personal experience with Walker’s story, about her conversations with Walker and about the influence The Color Purple, and the subsequent film and Broadway adaptations, have had on generations of Black women, literature and culture.

Subscribe for more Radio Times

On first reading Alice Walker’s The Color Purple:

Marty Moss-Coane: Take us back to your 15 year old teenage girls self and your first reading of The Color Purple. And what was your reaction?

Salamishah Tillet: Well, my cousin’s girlfriend…gave it to me during the summer of 1991, right before my senior year of high school. And she gave me three books to read. One was The Color Purple. The second was Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, and the third was The Autobiography of Malcolm X, written by Alex Haley. And so the constellation of those three books literally changed the trajectory of my life and also gave me a vocabulary and I guess a history to understand racial and gender oppression in the United States. But The Color Purple in particular was just such a wonderful text because I discovered a new language in a new world through Celie’s perspective that I had never seen before.

On the dialect in The Color Purple:

MMC: You teach creative writing. The very first sentence of The Color Purple is: “You better not never tell nobody but God. It’d kill your mammy.” And then she goes on to say to God, “Dear God, I’m 14 years old. I am. I’ve always been a good girl. Maybe you can give me a sign letting me know what is happening to me.” As a writer I mean, you know, you need that first couple of sentences to to hold the reader.

ST: Yeah, and when you read it, when I read it, you’re like, what is going to happen in this book? And on a number of levels, I think it’s an unforgettable opening because, one, just the syntax. We’re in this moment in which the southern black girl is telling her story and Alice Walker is trying to get us as close to the rhythm of that language as possible. Alice said that she wanted to write a book that her her mother would be able to read – her mother from Eatontown, Georgia – and that’s also why she did the film eventually. This is the first novel that we have in which we have that language that has the richness and the flexibility and the fluidity of black Southern vernacular speech as the primary language of the novel.

On abusers:

MMC: You had a really, really provocative piece in The New York Times: “Can an abuser make amends? The Color Purple points the way.” This is a book that you have read many, many times and you say as a middle aged woman, you’re drawn to Albert and perhaps see him in a different light than you did, perhaps as a younger person reading The Color Purple. And then you ask, “How does one actually atone for violence they inflict on others?” And you say that, really, Albert helps show us the way. How so?

ST: Yeah, I wrote that piece obviously after the book is written and also during a period in which we as a country were really wrestling with the insurrection outside the U.S. capital. And there were all these, in the immediate days and weeks afterwards, there was this quick compulsion to have forgiveness on the part of certain legislators. “Can we get over it? Can we get past this moment? It wasn’t that bad.” And then also we’re continuing to be in the age of Me Too. And there’s also this kind of what are we going to do with these people who have harmed others? So that’s the backdrop. And I find The Color Purple and I find Albert to be such a singular figure. I find his attempt, as you point out, with the scene, we just listened to when Celie puts the curse on him, I mean, that is a turning point for Albert in all versions of the story: the movie, the musical and the novel. But I also found that in the musical, because we can see his complete and utter breakdown on the stage with the music getting frenzied and the lights flickering on and off, that Albert loses a lot as a result of the harm he has inflicted on others. And so you can stay in that position. You could deny the harm. That’s one choice. You can try to move past it and reinvent yourself as if you’ve never done that harm. That’s another choice. Or you can try to atone for the harm that you’ve inflicted by owning it and then by changing your life and then by repairing the damage that was done.

[138.9]

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.