Zero tolerance policy — and me

At times, I seem to be among the children taken from their families at the border. I hear my own cries joining theirs, desperate and helpless.

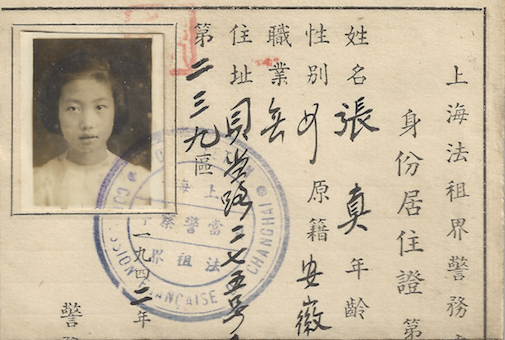

The fake ID for Annabel Liu. (Photo courtesy of Annabel Liu)

Recent news reports that our government is tearing thousands of children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexican border have taken me back to a night in 1941 when I was 6 years old. I woke up that night in a strange place, surrounded by strangers.

The shock and terror of suddenly realizing I was alone and totally helpless and vulnerable burned my psyche forever. I was never the same again.

Later, my older brother told me that I lived with two groups of strangers consecutively for half a year before my mother could retrieve me, but I don’t have a single trace of memory of it.

I’ve always been blessed with a good memory, and I have clear recollection of events before and after that period, but I don’t remember a thing from the instant when I realized I was completely alone to the day my mother took me back — those six months when I must have thought all members of my family were dead.

It’s been 77 years. I’ve consulted psychiatrists, psychologists, and family therapists. I’ve even tried deep-tissue massages and hypnosis. Those six months remain a blank.

I can’t blame my mother; it was war. I was 2 years old when Japan invaded China. My father volunteered for the resistance to fight the Japanese when I was 4, leaving my mother and three children in Japanese-occupied Shanghai.

We lived under the radar for two years when our luck ran out — the Japanese military police found out about

my father and came to arrest us. We barely escaped in time, and my mother was forced to separate us.

Although I don’t remember those six months, I can identify with what these migrant children are suffering. At times, I seem to be among them and hear my own cries joining theirs, desperate and helpless.

But I’m not one of them. I was much, much luckier than they are. I was reunited with my mother and siblings in six months, and my father returned in one piece after the war. Nobody can guarantee that to these thousands of children, some mere toddlers or babies.

Fortunate as I was, my childhood was cut in two. The healthy, happy-go-lucky little girl never returned.

Trauma of separation has not healed

After our “happy” ending, a thin, melancholic lookalike took my place. To be able to function, I required a lot of sleep, much more sleep than those of my age. At the same time, I became a lifelong insomniac, forever struggling to fall asleep and stay asleep.

I also grew sickly, contracting diphtheria, which required months of hospitalization and, afterward, complete bed rest at home. I never attended the latter half of elementary school.

Growing up, I continued to suffer various health problems and complications of the diphtheria and had to stay home from school a semester or a year at a time. But my emotional baggage is heavier than my physical handicap.

I’m an incorrigible pessimist, always waiting for the other shoe to fall, believing the worst scenario is my due.

I went through life making what I thought were cautious, rational, pragmatic decisions — only to discover in my old age while writing my memoirs, that many of those choices stemmed from being petrified of abandonment.

Perhaps for that reason, I’m incapable of enjoying life. I approach life with fear and distrust — not believing that anything good will happen. In fact, I always keep everyone and everything at arm’s length.

Emotionally, I might have been on the center stage of my life, giving what I thought was my all, yet a part of me has remained crouching, hiding in the farthest corner of the second balcony, with my arms wrapped around myself.

During World War II, England evacuated millions of citizens from cities to the countryside to protect them from devastating German air raids. Some school-aged children were evacuated without their parents, with their consent and cooperation.

Decades later, however, one man who was separated from his parents in childhood confided that, all his life, he struggled with the “3Bs” — bonding, belonging, and believing.

The fate of the thousands of children caught by an unimaginably cruel and inhumane Trump administration policy at our southern border is far worse. Ironically, President Donald Trump, who says he opposes abortion, has said that women who choose abortion should suffer “some form of punishment,” for he values “each and every life.”

Now we have thousands of children, ranging in age from a few months to under 18, in federal custody. Some of them are caged, dispersed to various undisclosed undisclosed locations in the country. Some of their parents have been deported. The odds are not good that these children will see their parents soon, if ever. There is no mechanism in place to remedy their dire situation.

How many of them will survive and be reunited with their parents is anyone’s guess. Whatever the outcome, there is one certainty: None of these children will come out of the separation and incarceration unscathed.

They will all be scarred for life.

Annabel Liu came to this land on a freighter in 1957. A bilingual writer, she has published three memoirs in English, “My Years as Chang Tsen: Two Wars, One Childhood” (second edition); “Under the Towering Tree: A Daughter’s Memoir”; and “Where Chopsticks Meet Apple Pie: Cross-cultural Musings on Life, Family, and Food.” She has also published a novel and seven collections of essays and short stories in Chinese

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.