Years after eminent domain in Hawthorne trauma lingers for some

Long before the Philadelphia Housing Authority set out to remake Sharswood, it rebuilt a section of Hawthorne, a neighborhood tucked just east of Broad below South Street. Hawthorne’s public housing complex was razed, private properties were taken by eminent domain, and in their place a new mixed-income neighborhood rose. In many respects the neighborhood is better off, but the same cannot be said for some former residents. For the Latimore family, which lost five properties to eminent domain, the compensation offered could never make up for the buildings, hopes, and community they lost in the process.

When the Philadelphia Housing Authority came to the Hawthorne neighborhood in 1996 with an ambitious redevelopment plan, Robert and Barbara Latimore had never heard of eminent domain. Nor did they suspect that, nearly two decades later, they would still be devastated by its power.

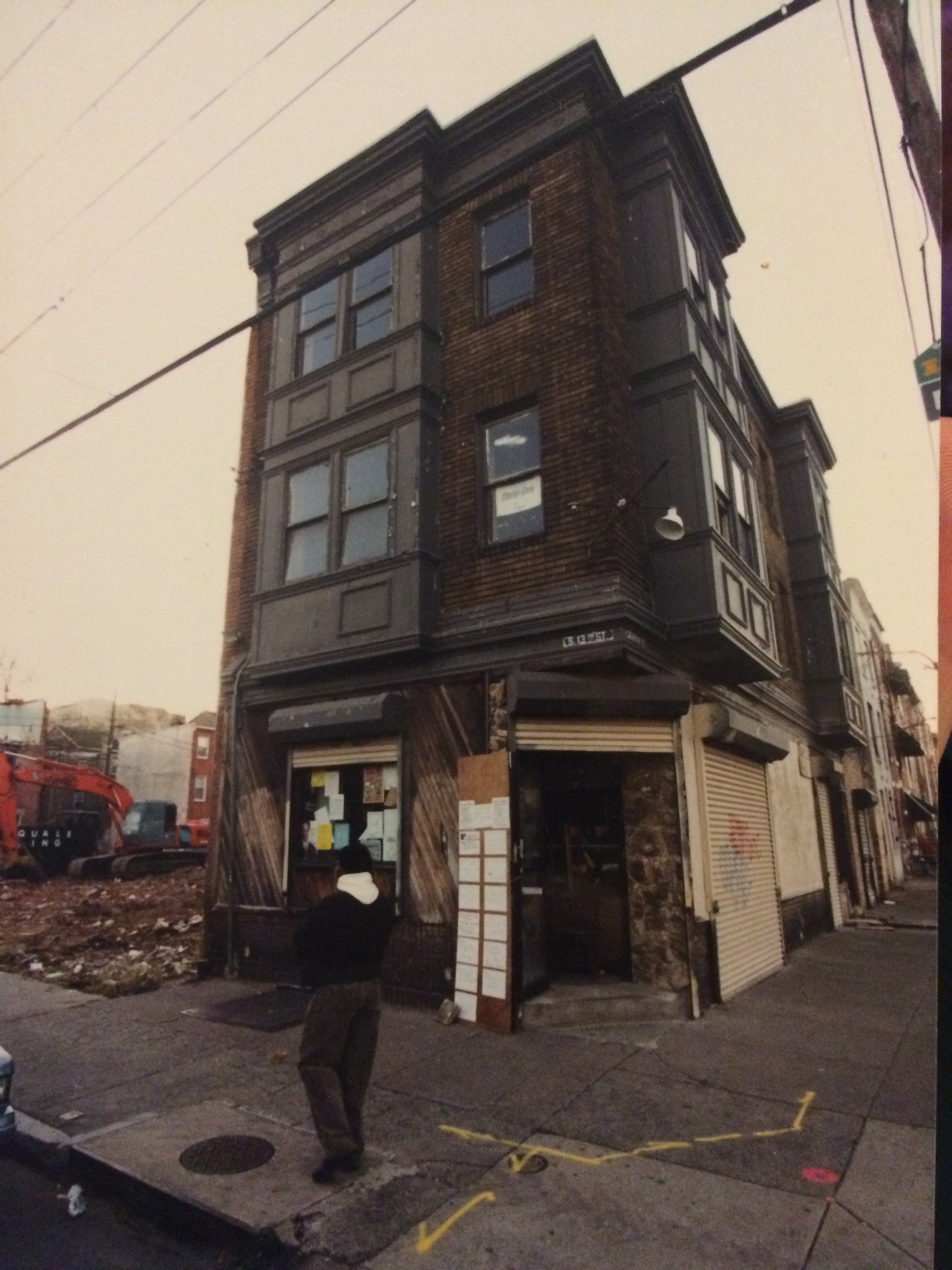

It all happened so fast: They got the condemnation letters in 1999. A year later, the city seized their five properties — the family’s corner store, three rowhouses, and an empty lot — and offered fair market value compensation. The Latimores refused, and 16 years later, they still haven’t taken the money on the table. In their eyes, compensation was, and is, not just about land value. Their neighborhood moved on without them, and they lost the opportunity to be a part of its growth.

“My whole history was within those three or four blocks — Catharine, Christian, Fitzwater, 12th and Broad,” Robert Latimore says of Hawthorne, the area wedged between Broad and 11th Streets, from South Street to Washington Ave. “It’s all gone now.”

His 73-year-old hands shake with tremors as he digs for the truth. The overstuffed storage box in front of him holds a fragmented record of the events: the condemnation notices, the newspaper clippings, community meeting minutes, cheery press releases with their carefully worded promises about a reborn neighborhood.

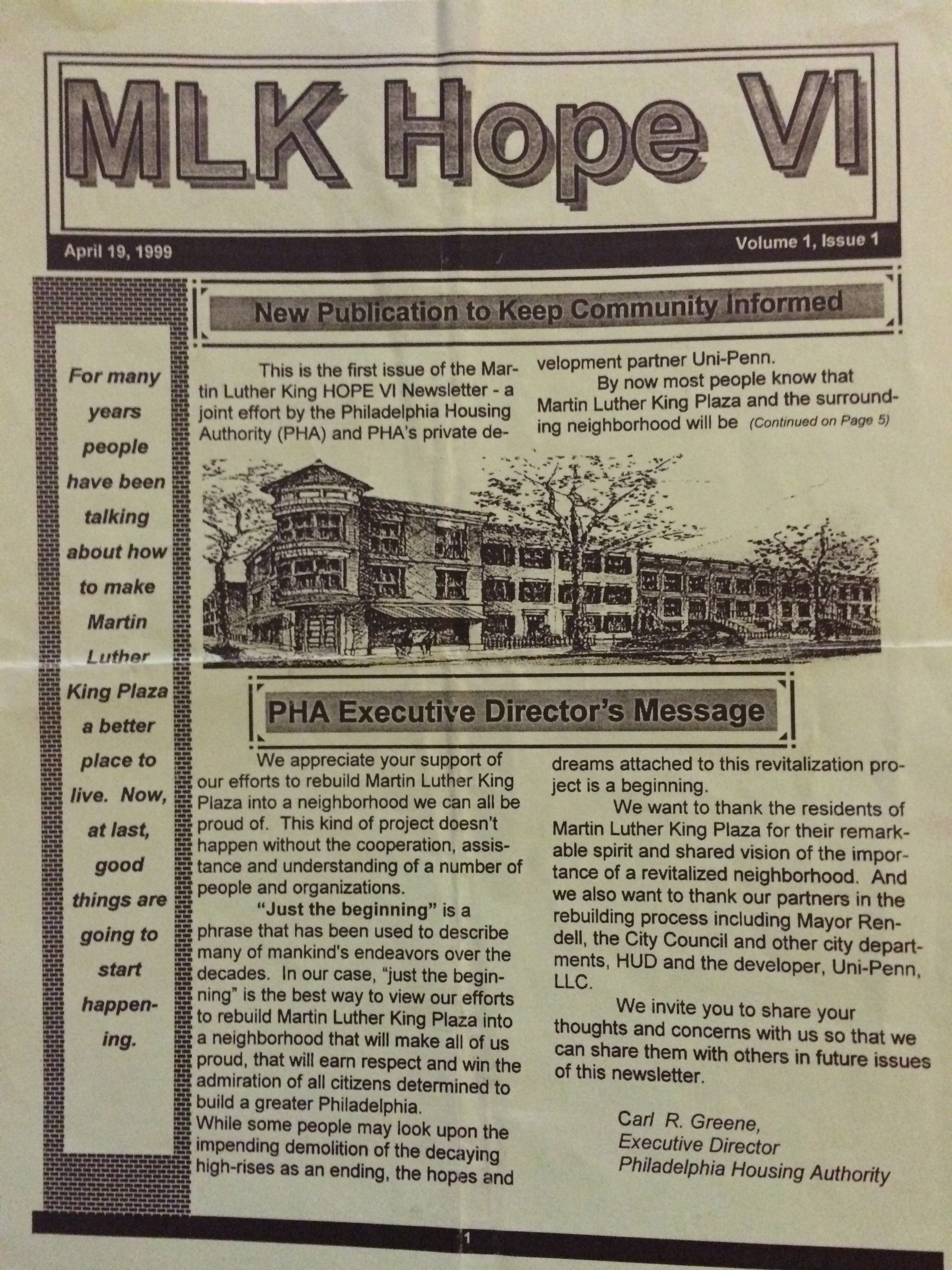

Latimore finds a yellowed newsletter from the Housing Authority’s (PHA) former Executive Director, Carl R. Greene, heralding the demolition of Martin Luther King Plaza, a troubled public housing complex built in 1960.

Most people, the Latimores included, were cheering him on at the time. In 1996, PHA had been awarded a $25.2 million HOPE VI grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to redevelop the MLK area in Hawthorne. The crime-plagued towers, vestiges of a failed public housing policy, would finally meet the wrecking ball. With the help of two developers (Universal Homes and Pennrose Properties, a.k.a. Uni-Penn) PHA would construct a new low-rise, mixed-income, mixed-race neighborhood — a neighborhood with “the kinds of houses that you already see in South Philadelphia today,” Greene’s newsletter read.

And PHA followed through. But not without leaving a few people behind.

Latimore pulls out another letter, this one written by his daughter to then-Mayor John F. Street, dated April 2000, six months after the towers returned to dust. “My parents desperately want to keep this property,” she wrote. “Please? Mr. Mayor, I pray that the doors will open for my parents so that they will be able to dream again and their dreams will become realities.”

From their Point Breeze rowhouse, all these years later, the Latimores are still trying to figure out if they should accept the money on the table, which they feel is insufficient, or keep fighting for compensation that accounts for both the loss of their properties and the pain that followed.

“Condemnation #14”

Eminent domain isn’t uncommon in Philadelphia for public or private development projects. Between 1992 and 2007, the city condemned and seized some 4,000 private properties for privately-developed projects, according to sociologist Debbie Becher’s 2014 book “Private Property and Public Power: Eminent Domain in Philadelphia.” However, less than 250 of those cases resulted in formal resistance — that is to say, residents who fought back against the land-grabs.

Most condemned properties are bruises of urban decay, long-abandoned structures and weedy vacant lots, for which few tears are shed. But in some cases, committed property owners like the Latimores are forced out against their will, and without proper legal aid, the outcome usually isn’t a happy compromise.

The reengineering of the Hawthorne neighborhood is a small-scale version of what is currently happening in North Philadelphia’s Sharswood neighborhood, where PHA recently kicked off a 10-phase, half-billion dollar neighborhood makeover.

Both projects stem from federal programs aimed at replacing distressed public housing with mixed-income neighborhoods. In both Hawthorne and Sharswood, the eminent domain component of the plan was brought to residents after the initial planning phase. Backlash ensued. But the reasons for that backlash weren’t always well understood by project leaders — perhaps because, as with the Latimores, it wasn’t just about deeds and titles. It was about home, it was about community, it was about a life’s work.

In Hawthorne, as in today’s Sharswood, residents were investing in their community’s future long before the Housing Authority drew up its blueprints.

Barbara remembers how proud their Hawthorne neighbors were when Robert first purchased his corner store in 1970. He was 28 years old with a fifth grade education, but a hard worker in the years since he left school. Working from a young age, he was determined to be his own boss one day. Turning Latimore’s Variety at the corner of 13th and Catharine streets into a family-supporting business didn’t happen overnight. For a decade prior, the couple says that they cast off indulgences in favor of saving money. They avoided restaurants, and for entertainment, they took the kids to the long-gone 61st Street Drive-In Theater, where admission was a dollar per car.

“Our life was about building a future for our children,” Barbara Latimore says.

She and her husband grew up in and around the Martin Luther King Plaza, and they were among the few families to become economic stakeholders in the neighborhood. By the early-1990s, development in Center City was creeping south into the deeply impoverished Hawthorne area.

Latimore’s Variety was burglarized and vandalized several times over the decades, but Robert never gave up on their community. If anything, he was a voice for more opportunity and inclusion for Hawthorne. In a City Paper article from that period, he criticized the expansion of the Avenue of the Arts for offering little to the neighboring black community in the way of economic development. He welcomed the promise of investment spurred on by gentrification to the north.

He bought four more residential properties within a one-block radius of his store and made plans to fix them up as rentals in the years to come.

“I was going to do what was happening in the neighborhood anyway,” he says.

When PHA’s redevelopment plan was first unveiled in 1996, Latimore attended the community meetings. He signed up to join the MLK economic development committee. He even wrote up a proposal — “turning a corner snack shop into a neighborhood fixture” — in an effort to show project leaders he was serious about matching the new Hawthorne image, property by property, brick by brick.

In 1998, city officials began informing residents that, in order to build the 250 replacement houses at the MLK Plaza, they would need to acquire properties beyond the tower site, and that they would walk the community through this complicated process. The taking of properties didn’t go smoothly, however.

No advance warning was given about lots being eyed for condemnation, according to multiple residents interviewed and meeting minutes reviewed for this story.

In early 1999, the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, contracted to assist PHA with the eminent domain, sent Robert Latimore a series of letters written in cold legal-speak. His life’s work was reduced down to a bloodless case number: “Condemnation #14.”

The making of “the list”

On October 13, 1999, indignant members of the Hawthorne Empowerment Coalition packed into City Council’s chambers. For six months prior, they had been at loggerheads with PHA, Uni-Penn, and their district councilman at the time, Frank DiCicco, over what they felt were wild miscommunications about the condemnation and eminent domain of their neighborhood.

A similar scene played out in the summer of 2015. Property owners in Sharswood facing condemnation made their case before the Committee of Rules, in hopes of having their properties removed from the list. The Housing Authority would cover relocation costs, and legal expenses if condemnees wanted to argue for higher compensation, but most of those seeking to undo their property’s condemnation were unsuccessful. Council ended up approving the taking of more than 1,300 properties, among which were 16 commercial properties with rental units and 57 owner-occupied residences.

The final list of properties that the PHA would seize to make way for the new Hawthorne was dramatically smaller. By the time of the Council hearing, they had trimmed the list from 231 properties down to 188, mostly to remove occupied units. But even at that scale, there was protest. The Hawthorne Empowerment Coalition had originally requested removal of 126 properties on the list. The Redevelopment Authority’s former Executive Director Noel Eisenstat agreed to strike less than half of those choices, and offer just compensation to all property owners on the final list.

Robert Latimore wasn’t alone on the chopping block.

There was Isabell McLaughlin, who had at that time lived 35 years at 1331 Catharine St. and had no interest in selling her condemned home to the city. Olivia Adams, a former member of the Hawthorne Empowerment Coalition and a property owner, said her property had been stricken from the list, but she was still fighting on behalf of remaining neighbors, particularly the Latimore family.

Her testimony was met with bursts of applause from the coalition.

“They are vacant but they are not abandoned,” Adams said of the Latimores’ properties, according to City Council records. “And that’s a distinction that needs to be made. [The property owners facing eminent domain] are the truest investors that this city will ever find. Why? Because they invested, not because of what’s going on, but in spite of what’s going on.”

But in Council’s eyes, Latimore was seen as a “multi-vacant-property owner.” Of his five properties, only the storefront was occupied at the time. Meanwhile, the project leaders had agreed to strike properties from the list that met certain criteria — properties that were currently owner-occupied, under construction, or showed progress toward rehabilitation over the next two years.

It wasn’t a rigid formula, though. Then-Councilman Jim Kenney called one property owner, Abdo Ellakany, a “slum landlord” of a blighted vacant that he had owned for 15 years. And yet the property in question, 1124 Carpenter Street, had been inexplicably removed from the condemnation list.

On paper, the Latimores’ argument looked persuasive — at least to their fellow residents. On multiple occasions, the family had shown commitment to rehabbing their properties once their financial situation improved. “It’s just a slow process for me, because finances have been slow,” said Robert Latimore, 57 at the time. Moreover, his corner store was a community landmark. Aside from a late water bill at one of the Latimores’ residential units — which he says he paid — all of their taxes and bills were up to date.

So why didn’t officials make a compromise?

During the battle over the list, Rahim Islam, CEO of Universal Community Homes and a community-developer liaison for the Hawthorne redevelopment, indicated that it was a matter of the big picture now. Latimore’s Variety was a corner property at 13th and Catharine Streets, and the city was aiming to develop all of the adjacent properties on that block.

“The goal is not to empower individuals but to empower a community,” Islam told the Inquirer before that Council hearing. “Yes, people have been holding these properties, but they haven’t been of benefit to the community.”

The next month, Latimore was hospitalized at St. Agnes Medical Center for a heart problem, which his family said was due to stress. Within a few months, the family says they learned from project developers that there wouldn’t be a two-year grace period to rehab their properties, even as some business owners with far fewer years in the neighborhood were permitted to stay.

The Redevelopment Authority told PlanPhilly that, by the end of negotiations with residents in early 2000, it condemned and seized a significantly smaller total of 119 properties to make way for the new Hawthorne. Titles on all five of Latimore’s properties were transferred to RDA in May 2000. But for the Latimores, that wasn’t the end of the battle.

First, they took picket signs into the streets. They pleaded with every politician in town. Then they sought legal counsel, as is their right in the eminent domain process. One of the family’s real estate lawyers, Mark T. Sophocles, sought to have Latimore’s commercial property revested to his name. The Redevelopment Authority told Sophocles that it wasn’t possible, as the property’s location was integral the construction plans for new housing, but relocation expenses could help the Latimores move the business.

The Latimores scoffed at the idea of relocating their store. They said that with the Redevelopment Authority’s original compensation package — about $73,000 for all five properties, plus $10,000 for relocation — they couldn’t replace what they had achieved in Hawthorne. And even if they could replace the buildings, money couldn’t buy new roots.

Fighting to bring attention to their case was difficult. A few articles in the local papers weren’t enough to sway the project leaders to change their minds. Legal counsel proved to be a headache of its own. The Latimores allege that one of the later lawyers failed to inform them of a court date in their complaint against the city.

To date, the family has not had their day before a judge.

How to right the past?

Robert and Barbara can’t recall how many times someone told them “I’m going to make everything right for you,” and yet as time went on, what was “right” in their eyes couldn’t be achieved anymore. The Latimores, who’ve been voting since they were of age, sought made their case before cycle after cycle of elected officials, from state representatives to new mayors, only to hear the same thing. “You better take the money before you get nothing,” they recall one politician telling them.

In the years after the first condemnation letters the Latimores still believed they had a fighting chance. So much so that when Robert went to the opening of the Kimmel Center in 2001, and got a poster of South Broad’s new landmark theater signed by former Mayor Ed Rendell and benefactor Sidney Kimmel, he had this thought: One day he would hang it up in his store. It had been more than a year since their properties were seized.

“For a while, I fought for the properties,” Robert Latimore says. “Even after they tore them down, I said I don’t care. I want my properties back, and I don’t care what’s on it.”

But reality sunk in after a couple years tangled in a nightmarish, bureaucratic land dispute. The Latimores reluctantly returned to the negotiating table.

The Redevelopment Authority’s initial market offer for the Latimores’ five properties was well under six figures. They took their case to the Board of View multiple times, and the Redevelopment Authority eventually raised its original assessment to $143,000, and then to $157,000, for their five properties. The authority confirmed to PlanPhilly that the Latimores’ settlement is still available, held in escrow. PRA’s spokeswoman Jamila Davis said via email, “if the Latimores are interested in obtaining the determined just compensation (barring any state obligations, liens, taxes, etc.), they can contact me, and I will place them in touch with the Law Department of PRA.”

The family says, however, they wouldn’t have sold even one of their properties willingly for that sum.

Of the 119 condemned properties in Hawthorne, the Redevelopment Authority settled 34 of them with the condemnees. Thirteen properties were city-owned at the time, and 72 were paid into court because RDA was unable to settle with the condemnees. But to the authority’s knowledge, the Latimores are the only former property owners from Hawthorne still contesting their settlement.

In the first quarter of 2016, the median home price in Hawthorne’s zip code was $330,000, according to HomExpert realty report. This fact does not escape the Latimores when they think about how things could have ended differently. They had once dreamed of leaving behind a property for each of their children, and their grandchildren, but nowadays, the Latimores can’t afford to replace a broken window in their own house. The toll of this saga has cost them far more than the market value offer.

“What we’ve gone through didn’t have to be, and I truly believe that they owe us for the pain and suffering,” Robert Latimore says.

The Latimores’ is an exceptional case of eminent domain prolonged and gone wrong. From the fall of the MLK high-rises to the balanced socio-economic fabric of the neighborhood today, public-housing advocates view Hawthorne’s redevelopment as one of PHA’s greater successes, and eminent domain an imperfect but necessary stepping stone to its achievement.

Observers both in and outside of government, however, cite fundamental problems in the way the city thinks about eminent domain. Under the Sharswood redevelopment plan, just 73 of the more than 1,300 condemned properties are occupied. Earlier this year, a group of PennDesign graduate students spent 15 weeks on data analysis, historical research, and interviews with both PHA officials and Sharswood residents. Their main takeaway was that PHA could meet all of its goals without condemning a single occupied property.

At the heart of such studies is hope for a more sensitive approach to urban redevelopment — or, at the very least, avoiding common mistakes of the past.

Society Hill’s much-praised transformation in the 1960s forced out many lower-income African American residents. Then there were more unequivocally disastrous redevelopment projects like the one in the city’s Eastwick section in the 1950s: more than 2,000 acres taken by eminent domain, 8,636 residents evicted, and a promise of urban renewal that remains unfulfilled 60 years later.

In a recent panel discussion about eminent domain, former Redevelopment Authority director Brian Abernathy (who is now the First Deputy Managing Director of Philadelphia) said that the authority has made “a reputation for pushing black folks out for white folks.” He also called condemnation “a violent act.”

“Condemnation, at its very heart and soul, is traumatic,” he said. “The emotions wrapped up in property are very real. And the government has done a generally poor job in recognizing that trauma and the emotions.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.