With no state budget and much uncertainty, Pa. schools expect ‘convoluted’ budgeting process

Listen

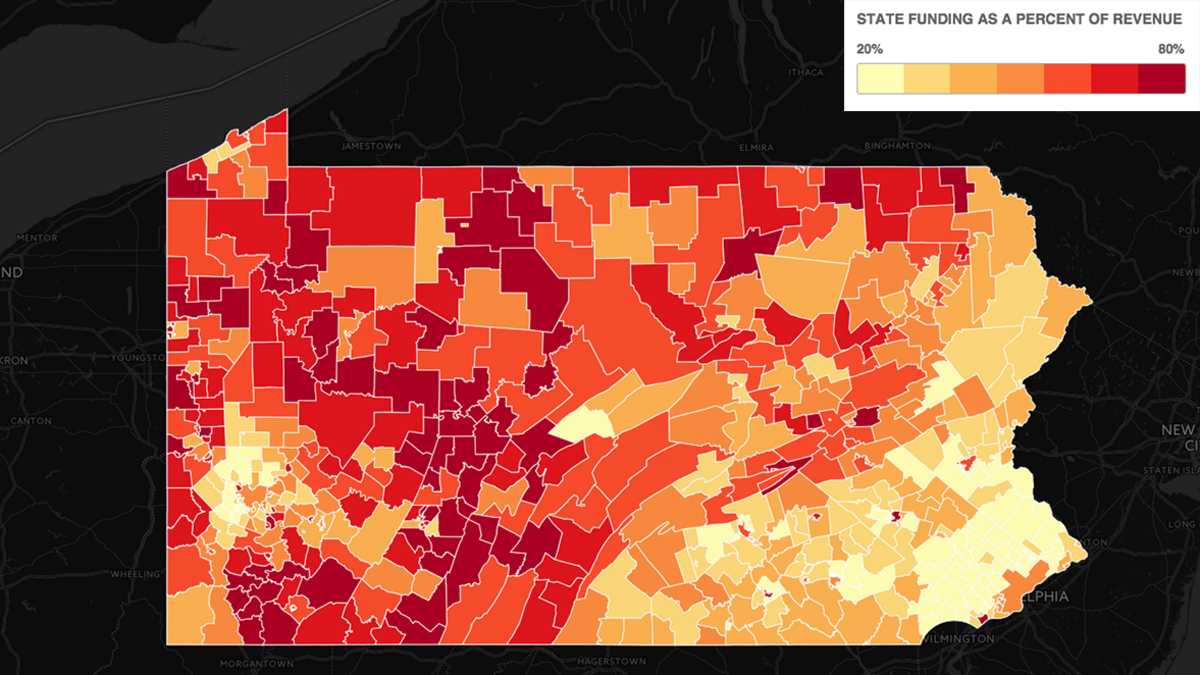

This map shows what proportion of school funding, by district, comes from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, according to 2015 data. (Data visualization by Rachel Feierman)

This week, Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf announced a plan to dramatically increase education funding. But heading into 2016-2017 budget negotiations with the current budget still unfinished has created a funding landscape that is “perplexing” and “convoluted” for public schools, say superintendents around the commonwealth.

“Until we know more about the funding, it makes it very difficult when you have two budgets you’re looking at right now,” said Michael Braun, business manager for the Morrisvile School District in Bucks County.

A small, blue-collar district, Morrisville cut some art and science classes when its state funding was reduced across the board in 2011. The governor’s budget proposals aim to restore some of the funding that went away, but have faced an uphill battle in the state legislature.

Some schools hit hard by those cuts are now just holding on — with the added challenge of complete uncertainty about when they’ll get money and how much.

“Costs go up all over the place,” said Braun. “Your retirement, Social Security, your medical benefits. They’ve all gone up.”

Those costs are legally mandated, said Braun, so the money must be found by taking it away from something else.

Morrisville gets about a quarter of its funds from the state. Many districts in the commonwealth — mostly rural districts and urban centers — get more than half of their funds from state coffers.

The Reading Area School District is relying on Pennsylvania for 73 percent of its 2016-2017 budget. To fill the whole left without state funding, the district has taken out two loans, according to superintendent Khalid Mumin.

“Right now, we’re at a point where we’re paying $800 a day, in interest, on a $20 million loan,” he said. An emergency disbursement at the end of December means the district hasn’t had to tap the second loan, for $30 million. Mumin said he expects to start drawing from it in March.

Districts borrow $900 million to keep running

At the end of 2015, the Pennsylvania auditor general’s office tallied $900 million in loans taken out by school districts across the state. Philadelphia, by far the biggest school dsitrict in the state, borrowed $525 million. Interest payments for those loans factor into school budgets, with no guarantee the state will pick up the tab its prolonged negotiations incurred.

“We’re struggling to stay afloat at this point,” said Mumin. Like many districts, Reading has been negotiating with some of its contractors to cut costs wherever possible. For next year’s budget, Mumin said, Reading school officials will plan on a 1 percent increase in expenses, but no more money from the state.

Several constraints hamper Pennsylvania schools’ ability to stay solvent during a prolonged state budget impasse.

First, school districts with less robust tax bases get more money from the state. Second, state funding for schools dropped precipitously in 2011. That means schools have been making do with less for five years, cutting staff and stripping fund balances.

Finally, Act 1 limits how much districts can raise property taxes to pay for schools in a given year, although there are exemptions.

Even school districts that don’t get — proportionately — that much money from the state are frustrated.

The Spring-Ford Area School District bridges Montgomery and Chester counties and gets about 17 percent of its funding from Pennsylvania. Raising taxes is an option that many districts have chosen, but one Spring-Ford is not willing to consider yet, said school board president Joe Ciresi.

“We can’t go back to taxpayers and say we’re going to raise taxes to 5 percent because the state didn’t give us anything,” said Ciresi.

Instead, officials are looking for places to trim costs.

For some districts, “trimming” means choosing between calculators students use on statewide tests and new textbooks. Or, it means putting off much-needed building repairs, said Nathan Mains, executive director of the Pennsylvania School Boards Association.

“I think we’ll be figuring out the impact of this budget stalemate for years to come,” he said of the fallout of delayed repairs and stop-gap curriculum fixes.

While it doesn’t look like any schools will have to shut their doors yet, some administrators are throwing up their hands. This week, the Erie School District officials announced they will have to seek a state takeover if they don’t receive more state funds. School leaders there blame Harrisburg for pushing them into the red and forcing the district to exhaust its fund balances.

In a recent meeting, school district leaders in Mercer County in Western Pennsylvania discussed not passing their own budgets, in protest. Without them, schools would not open in the fall.

“My suggestion was that we all cancel the first Friday night football game” instead, said Brad Ferko, superintendent of the Sharpsville Area School District, which touches the Ohio border in Mercer County. “I truly believe that would be noticed by more people than some other thing.”

The bottom line, said superintendents across the commonwealth, is the uncertainty means they will be spending very, very conservatively until there is a state budget.

At the end of 2015, Wolf used a “blue-line veto” to release a portion of funds to schools. Predictions on when a completed 2015-2016 budget would deliver the full amount are far ranging, said Mains.

“I’ve heard April,” after the Pennsylvania primary, he said. “I’ve heard some pessimists say this may not happen until the November election, and that would be devastating for the public schools.”

In the meantime, schools keep plugging away because they have to.

However, just because schools continue providing instruction shouldn’t be taken as a sign that they aren’t in serious trouble, said Ferko.

“The message from Sharpsville [Area] School District is we’re not OK,” he said. “We’ve been trained to say to the public, ‘Yeah, we’re going to make it, we’re going to be OK.’ But you know what, we’re not.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article misrepresented how much money the Philadelphia School District borrowed as compared to other districts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.