Will this round of Pa. redistricting be another all-out war? It’s all in the details

Being willing to split towns and counties might actually be more fair, mapping experts argue — even though it goes against old school conventional wisdom.

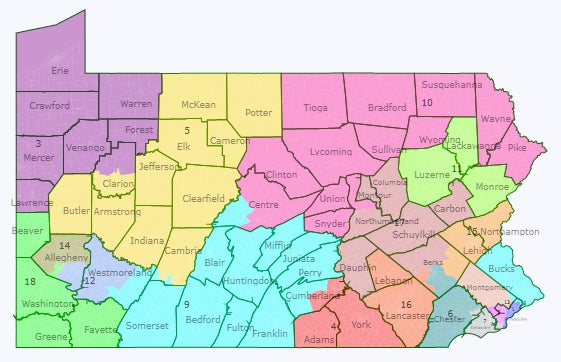

A close-up of a Pennsylvania congressional map. (Office of Gov. Tom Wolf)

Pennsylvania lawmakers are starting the fraught process of drawing new maps for congressional and state legislative districts. And already, they acknowledge that major points of contention will need to be ironed out before the maps take effect in 2022.

One big question: How hard should mapmakers try to match up district lines with county and municipal borders?

Generally, everyone involved in the redistricting process agrees a good map doesn’t split counties or municipalities excessively. But a key Republican in the mapmaking process, Sen. David Argall (R-Schuylkill), recently took that rule a step further, pushing a bill through his committee that would have essentially banned splitting municipalities unless strictly necessary for population reasons.

The bill won’t pass before the redistricting process is done. But Argall says he still intends to uphold the approach in the negotiations to come.

On the other side of the issue are mapping experts like John Nagle. He’s a professor emeritus of physics and biological sciences at Carnegie Mellon University turned self-taught mapmaker, and has simulated a lot of maps using Argall’s criteria.

On its face, keeping municipalities whole is neutral, he noted. But in simulations, he says the outcome is consistent: Republican candidates benefit, even though more Pennsylvanians are registered as Democrats.

“As long as non-splitting is a tier one criterion, one can’t draw a fair map in Pa.,” Nagle said.

A delicate balance

Not splitting communities is important, acknowledges Carol Kuniholm, who leads the advocacy group Fair Districts PA and works closely with Nagle.

Splits can hinder voters’ ability to make their voices heard on local issues, she said, but completely avoiding splits can have implications that go beyond community boundaries. In a recent Fair Districts project that collected dozens of draft maps, Kuniholm found that approach actually ended up diluting the voting power of minority groups.

“To say, ‘well, we’re not going to split anything and we don’t really care what the proportional representation is for minority communities,’ that’s not ok,” she said.

Back in June, when lawmakers were still hoping to adjust state laws in time for the current round of redistricting, Kuniholm and Fair Districts spent months working with lawmakers on a bill to create guidelines they thought would appropriately balance two priorities: creating compact districts that don’t split municipalities too much, and ensuring voters’ voices are proportionally represented.

It would have stipulated that first and foremost, no municipality or ward should be divided “unless absolutely necessary,” and that a map should never “dilute or diminish” minority voters’ abilities to form coalitions to elect candidates of their choice.

A second tier of rules said that as long as the first criteria were followed, mappers should also try to keep “communities of interest” intact, have district lines follow natural boundaries, and make districts as “responsive” as possible, i.e. a map should accurately reflect voters’ preferences.

But in moving his redistricting bill through committee, Argall gutted and replaced the Fair Districts bill with his own, paring it down significantly and making preventing municipal splits the top goal.

His rationale? Clarity. “Communities of interest” can be interpreted in different ways, Argall said, but “when you look at a municipal boundary line, everyone can see it.”

He has fought repeatedly against map plans that would divide Schuylkill County, where he lives. “Schuylkill County is not a large population county,” he said. “The fear is if you split us into two or three or four pieces, those voters will be completely ignored.”

Compact, contiguous, confusing

Thanks to vague laws on both the state and federal levels, Pennsylvania officials have a lot of latitude when deciding how to draw districts.

The only official criteria for congressional maps, which are drawn by the legislature and approved by the governor as simple legislation, is that they must be of about equal size and can’t dilute voters’ voices on the basis of race.

A 2018 Pa. Supreme Court decision also held that congressional districts should be compact and contiguous, and shouldn’t divide municipalities and wards unless absolutely necessary.

The Pa. Constitution gives its own, similar criteria for state House and Senate maps, which are drawn by a five-member committee made up of leaders from both parties and caucuses, plus an non-elected tiebreaker: they should be compact, contiguous, and avoid unnecessary divisions.

Thanks to recent population shifts, Pa.’s new congressional map must also have one fewer district than the version that currently exists.

Apart from those rules, it’s up to lawmakers to decide exactly how compact districts should be, for instance, or how many municipalities can reasonably be split or even how to decide whether a map is successful.

What is a fair map?

That’s a question Nagle, the mapping expert, has asked himself often over the past decade or so.

He first became seriously interested in Pennsylvania’s routinely fraught redistricting battles around 2012, the last time lawmakers redrew the maps.

It was a banner year for Republicans. They controlled the legislature and governorship and held a majority in the state Supreme Court, where map conflicts almost always end up. The maps that resulted were widely seen as favoring Republicans, and two — the state Senate map and, much later, the congressional map — were ultimately thrown out and redrawn at the behest of judges.

Nagle began thinking seriously about how one might draw a Pennsylvania map that accurately reflected the state’s political makeup. And then he hit upon an inherent quirk of Pennsylvania’s current political geography: like other redistricting experts, he found it’s much easier to draw a map that leads to Republican majorities.

Democratic voters are packed densely into Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, creating huge majorities in those regions, while Republicans hold narrower majorities across a far wider geographic area. Because big margins don’t usually make a difference — winning candidates just need one more vote than their opponents — that kind of spread is what’s known in redistricting as the efficiency gap. Having a lot of people of the same party close together doesn’t help win elections.

Nagle argues that if the point of a map is to proportionately represent voters across the whole state, then the efficiency gap should be addressed.

And he figured out a method he thinks accomplishes that: just be willing to divide a few more counties and municipalities.

In a 2019 paper Nagle published in the peer-reviewed Election Law Journal about this approach, he argued that adherence to traditional criteria, “prohibit[s] the worst abuses of partisan gerrymandering,” but “do not necessarily prevent unintentional gerrymandering which comes about from political geography.”

Argall, the Schuylkill County Republican, said that’s not an argument with which he’s familiar. And he balked at the idea of trying to circumvent political geography. He also said that kind of map engineering has proven to be a recipe for partisan bickering — and inevitably, lawsuits.

At the top of his mind is the 2018 case that saw the Pa. Supreme Court label the state’s congressional map a GOP gerrymander and redraw it — still a thorn in the side of many Republicans.

“We need to be very careful in this regard,” Argall said. “If our intent is not a hundred percent clear, there’s a very good possibility that judges somewhere will twist our language and say, oh, this is what we think they meant.”

“A challenge and an opportunity”

It’s still early enough in the map-drawing process that lawmakers and advocates haven’t yet begun to get deep into the technical criteria that will so dramatically affect their final map.

Lawmakers in the House State Government Committee held the first in a long, planned series of redistricting hearings last week. Their counterparts in the Senate committee that Argall leads have also committed to public hearings. All together, it’s a strategy lawmakers on both sides are touting as their most transparent redistricting process to date.

Mapping advocates are requesting consistency and transparency:

- lay out clear guidelines for the process ahead of time, and accept feedback on them;

- allow people to submit draft maps, actually consider them, and provide answers for why they would or wouldn’t work;

- and when lawmakers have a potential map, allow people to comment on it.

“It’s both a challenge and an opportunity,” Committee of Seventy President David Thornburgh told House lawmakers at the July 22 hearing. “You have a commonwealth full of citizens that [are] more conversant in this, more aware of the circumstances and the meaning of the maps, and I would encourage you to take advantage of that rather than…insist that we’re back in 1991.”

Argall is just one of several lawmakers who will have key roles in the map-drawing process. He says he’s been working closely with members from across the aisle, like Sen. Sharif Street (D-Philadelphia). Argall’s counterpart in the House, Seth Grove (R-York), also expressed a desire to come up with a compromise plan, one Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf will be willing to sign.

Argall noted that though he plans to stick closely to traditional, easy-to-understand mapping criteria, it’s still early in the process, and he’s willing to “consider anything.”

“I feel optimistic at this stage,” Argall said. “Perhaps in another month or two I will be less optimistic. The clock is ticking.”

Get more Pennsylvania stories that matter

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.