Why the United States owes its Navy to pirates

ListenWhen the United States of America was young, the question of whether or not to have a navy was tricky. America had maintained a navy to win independence from Britain, but navies are expensive. Once the Revolutionary War ended, the new nation — swimming in debt — dissolved the navy.

Then came pirates. Algiers would send out pirates from the Mediterranean coast to seize cargo and kidnap sailors. More than a hundred sailors — and the equivalent of tens of millions of dollars — were hijacked by pirates in just a few years.

About 90 percent of federal revenue at the time came from taxes on merchant ships, so the pirates of Algiers were making a serious dent in the America’s fragile economy.

“They said, ‘We won’t kidnap your ships if you pay us tribute,'” said Independence Seaport Museum curator Craig Bruns. “Congress said, ‘Is it cheaper to pay the tribute every year — a bruise on American ideals — or do we build a navy and go get ’em?'”

Bruns curated “Pirates and Patriots,” a new exhibition of maritime artifacts, models, and documents (including a letter written by a group of captured sailors pleading for help) describing the knotty circumstances that gave birth to the American navy. It was not a slam-dunk decision. Congress spent years debating that economic formula of paying Algiers’ tribute versus funding a navy. Newspapers, pamphlets and theatrical plays made arguments for and against the cost of establishing a navy.

And some at the time recognized that the horror and indignity of American soldiers being kidnapped into slavery by pirates was not so dissimilar from America’s own, sanctioned slave trade.

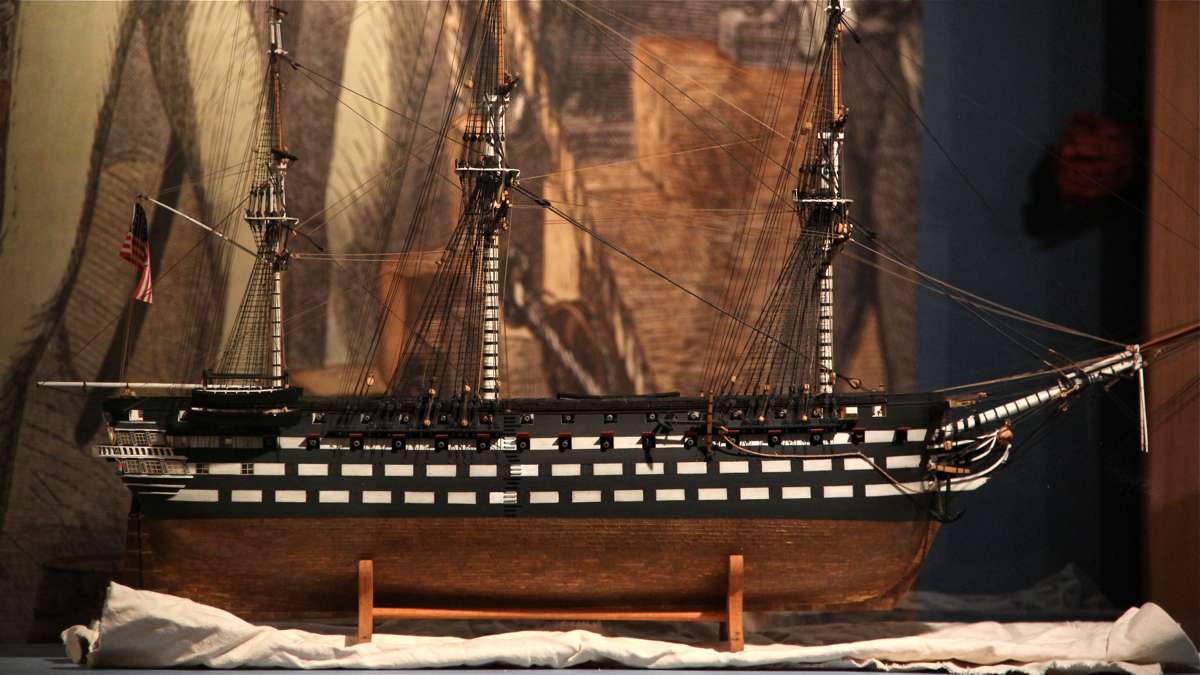

Finally, in 1794 Congress met in Philadelphia to commission six frigate ships outfitted with cannon that would protect the American shipping trade.

Two years into construction of those ships, a treaty with Algiers was struck. With the threat of pirates abated, so was the urgency to spend more money building boats. The six-ship navy was reduced to three.

“But we got our navy, is what I’m saying,” said Bruns. “Only three ships, but we got our navy.”

With an agreement in place with Algiers, there was little for the small fleet to do. it saw some action during the undeclared Quasi-War with France in 1798 and subsequent Barbary wars. Building a larger, more powerful navy was spurred by the War of 1812 and the burning of the White House by the British.

The exhibition drives home the Philadelphia roots of the U.S. Navy. The designer of those first six frigates was Joshua Humphreys, a shipwright with a yard at what is now Washington and Delaware Avenues. The new navy’s flagship, the United States, was built there. (The more popular, surviving ship of the fleet, the Constitution, was built in Boston.)

Humphreys is the central figure of “Pirates and Patriots.” At least two other men can lay claim to be called ‘Father of the American Navy,’ including the Revolutionary War naval commander John Paul Jones, and the country’s first post-war naval commander, Commodore John Barry. The Seaport Museum makes the case for Humphreys to share the moniker.

Humphreys had been a military ship designer since the Revolutionary War; his design for a massive, 74-gun war ship to defeat the British was waylaid when British troops captured Philadelphia. The miniature model he carved to win the commission is in the exhibition.

Later, at the launch of the first American navy ships, Humphreys hoisted a glass at the still-extant City Tavern on 2nd street and toasted the nation’s military might: “May the infant navy of the United States, like the infant Hercules, even in its cradle strangle the serpents which would poison American glory.”

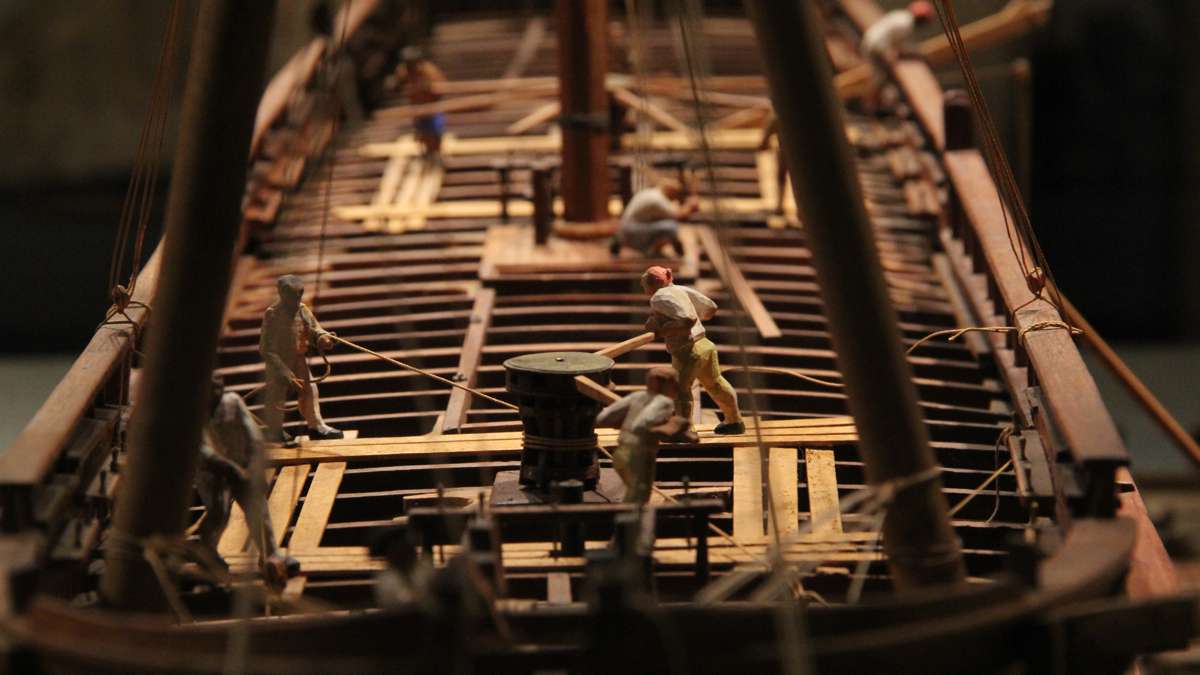

A topsail schooner originally designed by Humphreys in 1797, the Diligence, outfitted with 12 cannon and put into service during the Quasi-War, has been re-created by the Seaport Museum: there is a hand-built, 65 foot vessel permanently installed inside the gallery.

Museum president John Brady hopes that the birth of the U.S. Navy as a cornerstone of the museum will put it on par with the city’s other cultural attractions.

“We see that as something that ties in to Independence Hall, Liberty Bell, history tourism, and so on,” said Brady. “So we wanted that exhibit to have real impact, and a 65-foot ship in the middle of your museum is impactful.”

The Seaport Museum already has a 19th century ship — the Olympia — and a submarine from the 20th. Brady says together, the three ships represent the sweep of American maritime history.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.