Why forbidden garages keep popping up in your neighborhood

If you ask Fishtown resident Matt Karp, garages that open onto the sidewalk are a plague afflicting Philadelphia’s rowhouse communities. They reduce the number of eyes on the street and intrude on the sidewalk, he says. And in these older areas of the city, developed before cars were common, they also rob precious street parking from neighbors who jealously guard every available space.

For all of these reasons, the city’s landmark zoning reform passed in 2012 included a ban on sidewalk-fronted garages. But over the past year, the Fishtown Neighbors Association (FNA) noticed the scourge of bleak additions, and other designs in violation of the code, weren’t stopping. In one case, the owner of a new four-story townhouse on Columbia Avenue wanted to install a garage on Belgrade Street, behind the building.

At a community meeting, the neighborhood group’s membership voted 67-to-76 against giving the property owner an out from the design code. The neighbors felt the structure would interfere with the pedestrian-friendly urban fabric they valued on the rowhouse-lined street. But today, the parking garage stands. Neighbors still grumble about it — and about the numerous other examples of property owners running roughshod over the zoning that theoretically guides how development happens in their community.

How does it happen that a code passed into law through an arduous democratic process is routinely and legally skirted? The answer can be found on the 18th floor of 1515 Arch Street where the city’s Zoning Board of Adjustment meets twice a week to hear zoning board appeals, according to a new draft report from Philadelphia’s City Planning Commission.

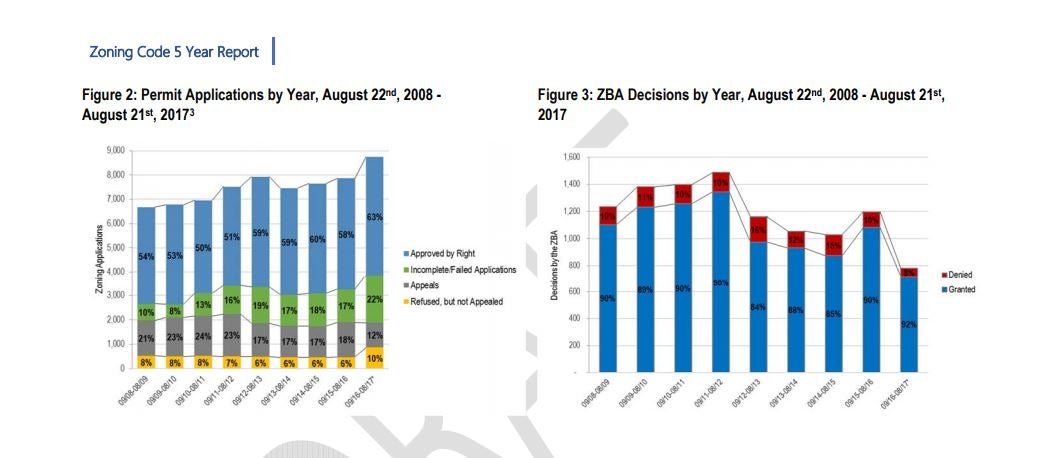

The commission found that even in neighborhoods where zoning maps have been updated, the mayor-appointed board still overrides the new rules the vast majority of the time. Last year, the board approved 92 percent of zoning variance cases they heard, according to city data.

“The Zoning Board of Adjustment may not yet be attuned to the massive amount of collaboration that happens between all parties to ensure that these [zoning] changes are just and necessary,” reads the report. “This is important to the future of development in Philadelphia and the future of the Zoning Code, and it’s [sic] ability to positively affect change.”

Michael Nutter’s rewrite of Philadelphia’s zoning code is a modest success, according to the report. But despite its achievements in elevating public participation and simplifying the development process, the report says, the ZBA’s overwhelming tendency to allow property owners to violate the design code has greatly limited its impact.

“I strongly agree with the… finding and recommendation in the report that states the ZBA is approving far too many variances,” says Karp, the former head of Fishtown Neighbors Association’s zoning committee. “This is undermining the entire zoning code reform and needs to stop.”

A broken system or a sign of a thriving, changing city? Depends who you ask.

When reform was enacted in 2012, the Nutter administration promised the fresh zoning code would bring clarity to real estate development across the city. In the midst of the reformist fervor, there were even dreams that development could be accomplished with far fewer lengthy, and costly, trips to the jury-like board.

At that time, planners and engaged residents like Karp believed the ZBA had become a routine stop for builders because the zoning code that governed them was so outdated. After all, the last update happened before John F. Kennedy’s assassination. The old rules were meant to accommodate a midcentury industrial hub with a population of more than 2 million.

But by the early 21st century, the 1960s-era zoning strictures rarely conformed with the needs of modern projects, making it difficult to build without securing an out from the requirements. Composed of political appointees, including building trades union representatives and others with skin in the development game, the ZBA invariably gave property owners a pass unless they ran afoul of someone or something important to the city’s political class.

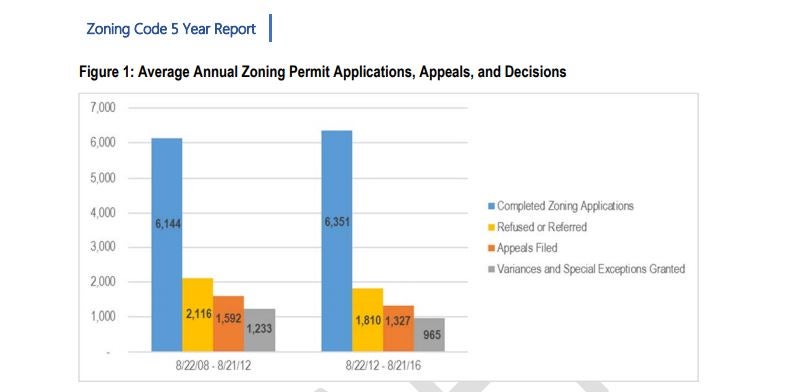

One of the primary goals of Nutter’s reform was to undercut the board’s prominence by both reducing the number of cases brought before it and by making the zoning commissioners look upon their supplicants with a more discerning eye. With a brand-new code and zoning maps that were brought up to date with the city’s new horizons, the theory was that there would be fewer cases before the ZBA. For those projects that did still come before the board, the commissioners wouldn’t be so willing to give a free pass to developers if their project clashed with the new and improved zoning. The Planning Commission’s new research finds that logic holds—but only to a limited extent.

“The bottom line is that the goal was to reduce the number of cases that needed variances and increase what was being done by right,” says Paul Chrystie, a press representative for the city. “The report shows that’s happening.”

Overall, there’s been an average decline of 265 cases a year since reform, despite substantially more zoning permits going to City Hall as development blossoms in and around Center City. Once a case actually arrives at the ZBA, however, the board remains resistant to policing property owners. In 2012, the board denied only 10 percent of decisions. In 2017, that number dropped to 8 percent. The Planning Commission says they’ve received persistent feedback from community groups who argue the board’s leniency chips away at civic engagement.

“The decisions of the ZBA often dissuade community engagement in planning processes, as members of the public conclude that variances will be approved regardless of their input,” the commission’s 57-page report concludes. “ It is time for the rate of approvals for zoning variances to fall.”

Of course, not everyone agrees with this conclusion. For many observers, the ZBA’s freehand with variances is just a routine part of the process. It is impossible for planners, they say, to predict how a neighborhood’s needs and desires will shift over the years. “I think it’s naïve to say that once we remap the city, we shouldn’t be handing out variances anymore,” says Leo Addimando, the vice president of the Building Industry Association. “The remapping is well-intentioned, but it is in conflict with the fact that neighborhoods are evolving every five to ten years. The fabric of the city is changing faster than it ever has in the past.”

Carl Primavera is one of the city’s most prominent zoning attorneys. He too says the pattern is here to stay. “Philadelphia is such a complicated city, with such a rich environment, that you can never just tell people to follow the code or don’t do the project.”

He believes that “every project of consequence requires relief. “That we are still granting variances at a high level is not a failure of the code. It’s recognition that the code steers in a general direction, but ultimately individual needs require some tweaking.”

The Planning Commission’s report doesn’t only focus on the role of the ZBA. It also explores other aspects of the new zoning code, including the pace of remapping, which is the process by which the zoning of specific neighborhoods is brought up to date under the guidance of local advocates, City Council, and the Planning Commission. But because Philadelphia’s political tradition gives its ten district city council people near total control over land use and zoning in their territories, many of the remapping proposals made by the Planning Commission haven’t progressed. More than half of the city is still zoned much as it was under the old code.

Remapping can’t be considered the only solution, the authors caution. They profile three remapped areas — Bella Vista, Northern Liberties, and the neighborhoods to the west of Temple University — and find inconsistent results. Although by-right development increased in Northern Liberties and Bella Vista, the ZBA continued to grant variances far more often than not.

“This dynamic shows that despite the best effort of skilled planners and vested community members to envision a ‘Plan,’ implementation is often thwarted by those who are better able to amass political and economic capital,” says Ken Steif, a lecturer in city planning at the University of Pennsylvania.

None of these problems are secrets in City Hall. Mayor Jim Kenney’s administration has said it is working to bring the ZBA in line with city planners and commissioners. Last summer, city officials moved the board’s staffers into the Department of Planning and Development, for example, which Chrystie describes as a means to better align their actions through proximity and co-education.

The Planning Commission itself provides guidance to the ZBA on individual cases. They have a staffer who attends each meeting and offers recommendations on each case. And they hold trainings for the whole board every year, and for new commissioners, to educate them in the intricacies and goals of the new code.

“I think we are going to start to see some positive benefit from having that ability to help to educate the zoning board on how best to use the info they are handed with each case,” says Andrew Meloney, a senior planner who presented the report’s findings to the Planning Commission this week.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.