Complex saga of Cramp Machine Shop is coming to an end

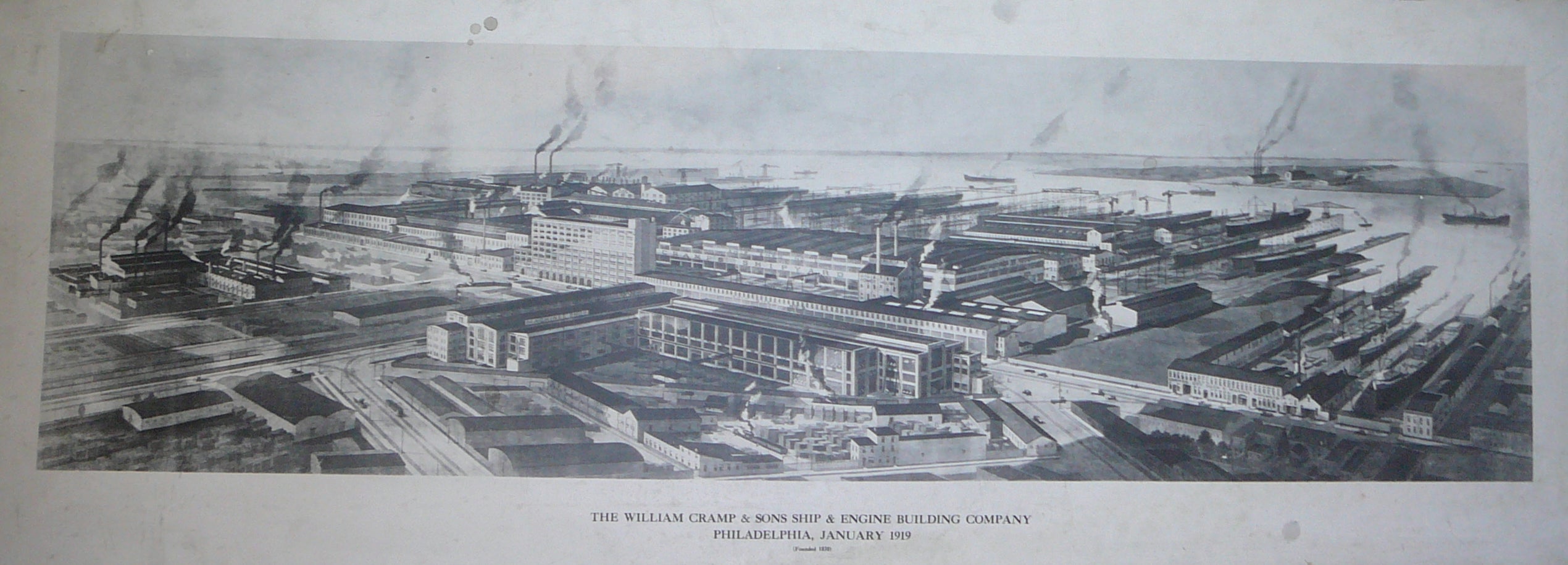

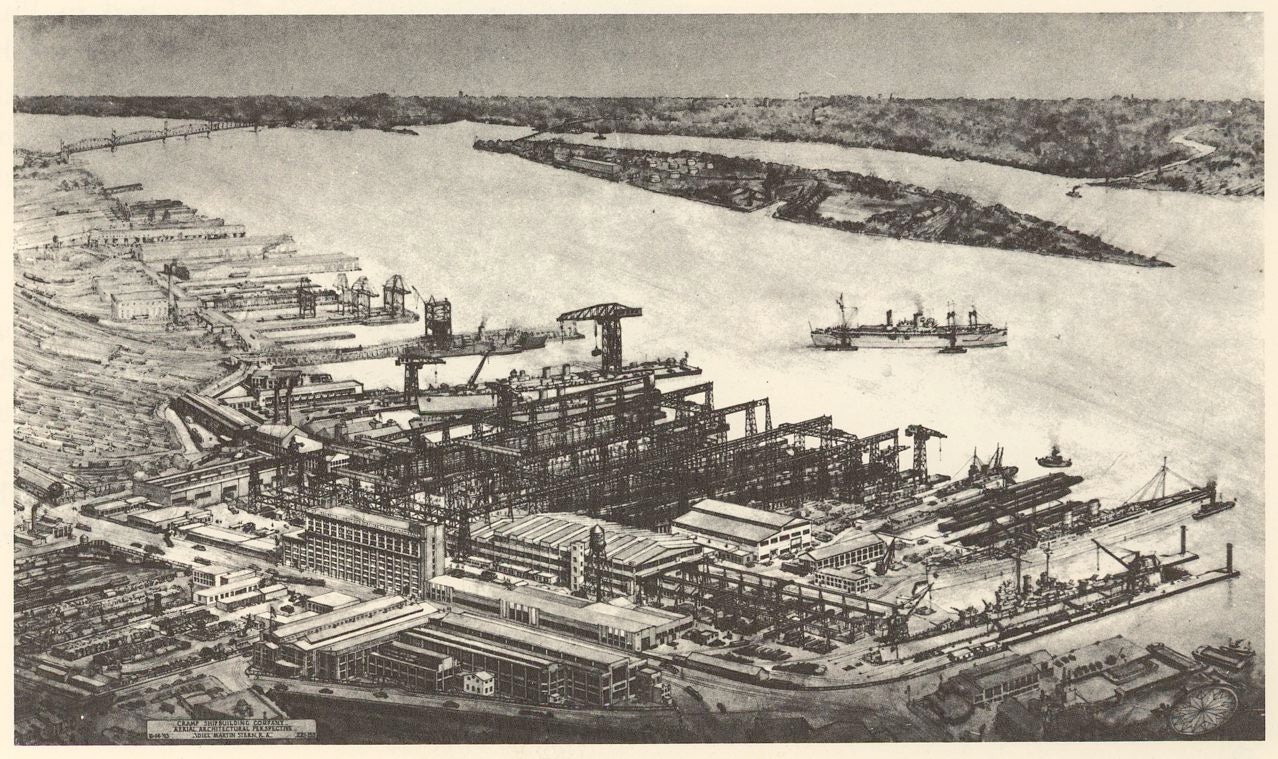

William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company constructed the industrial cathedral at 2050 Richmond Street nearly 100 years ago as a machine shop where enormous hydraulic turbines dwarfed the men who made them.

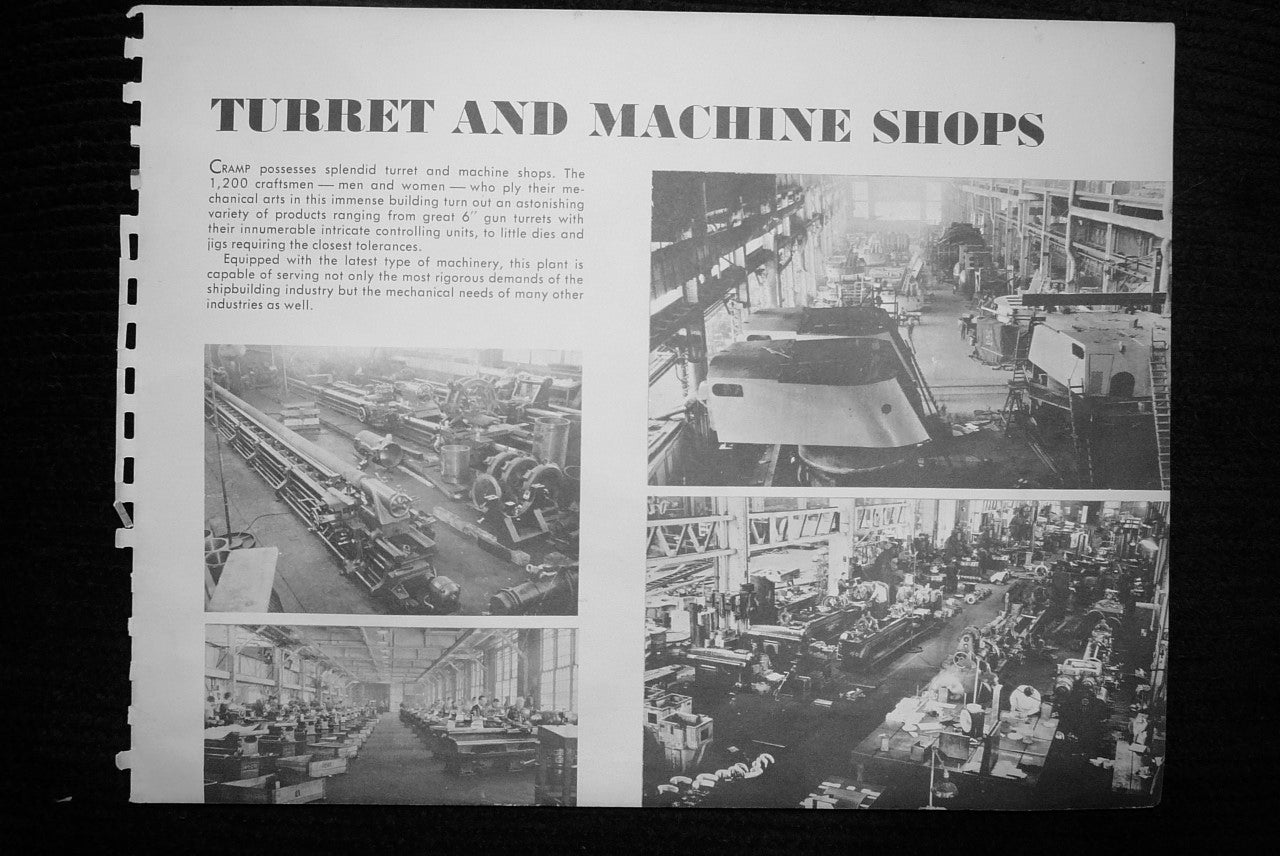

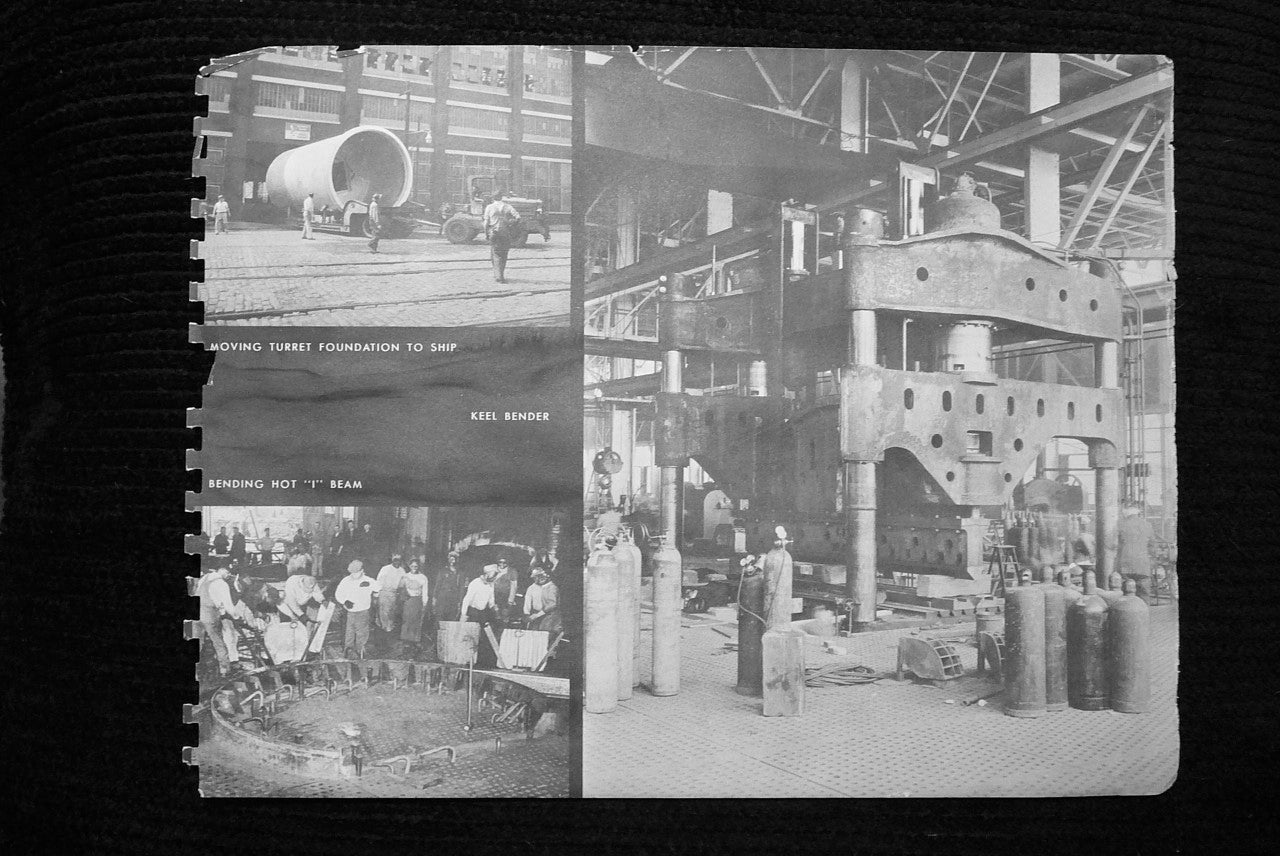

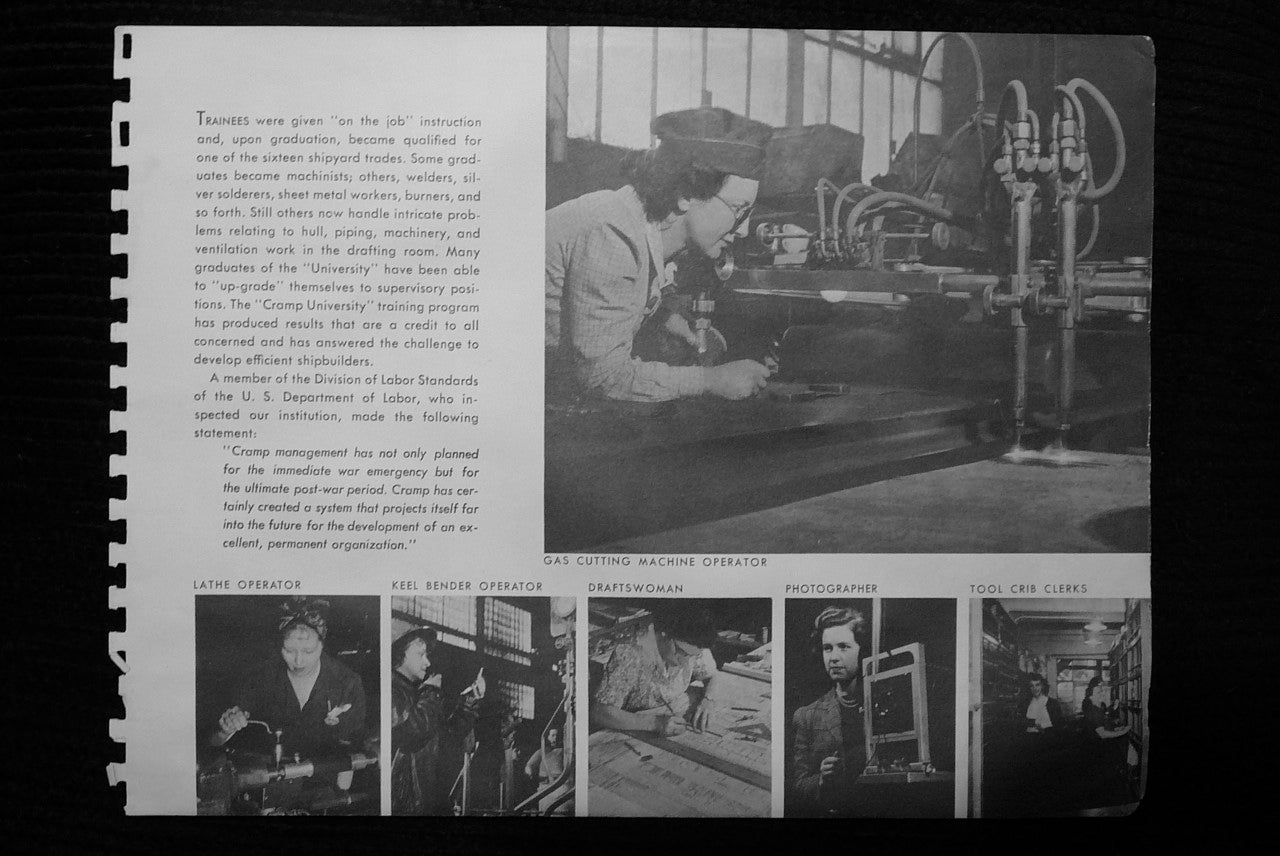

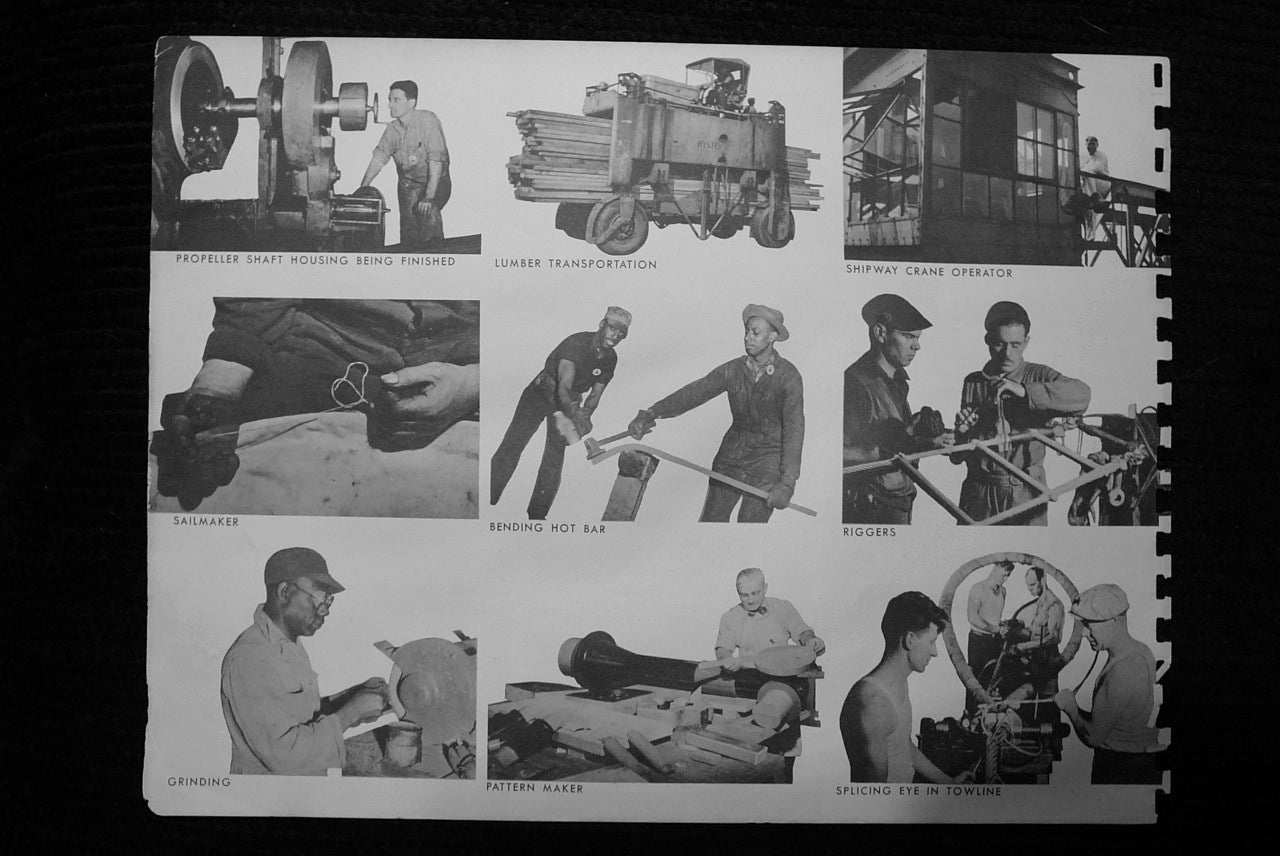

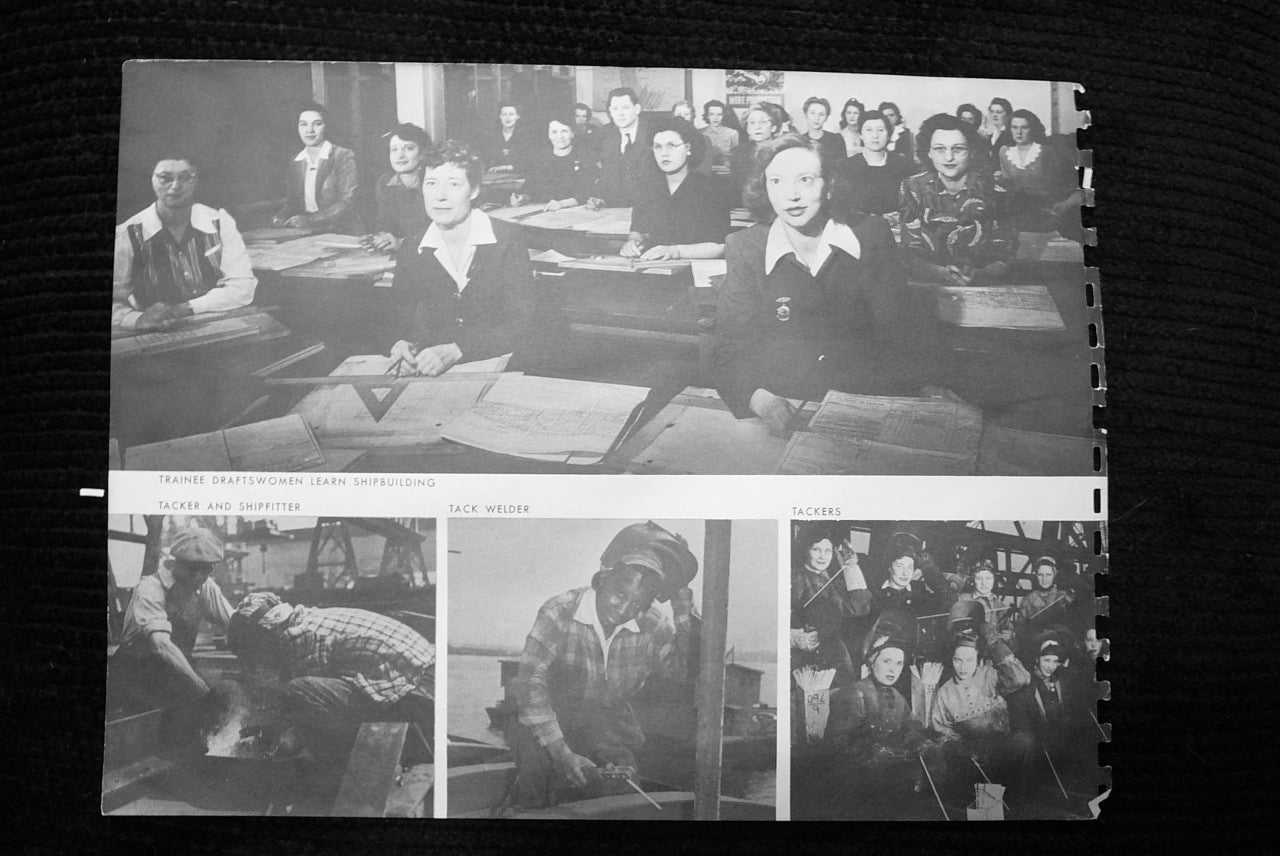

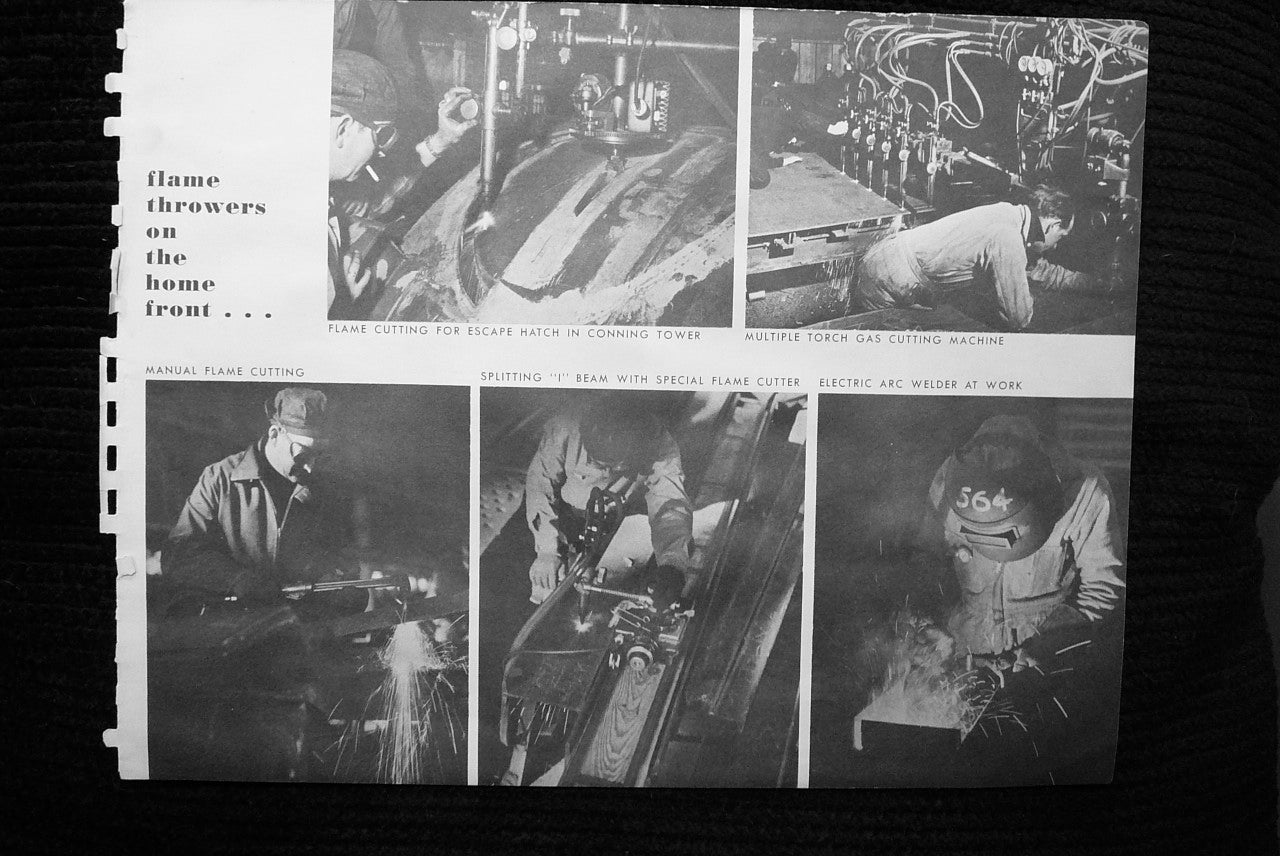

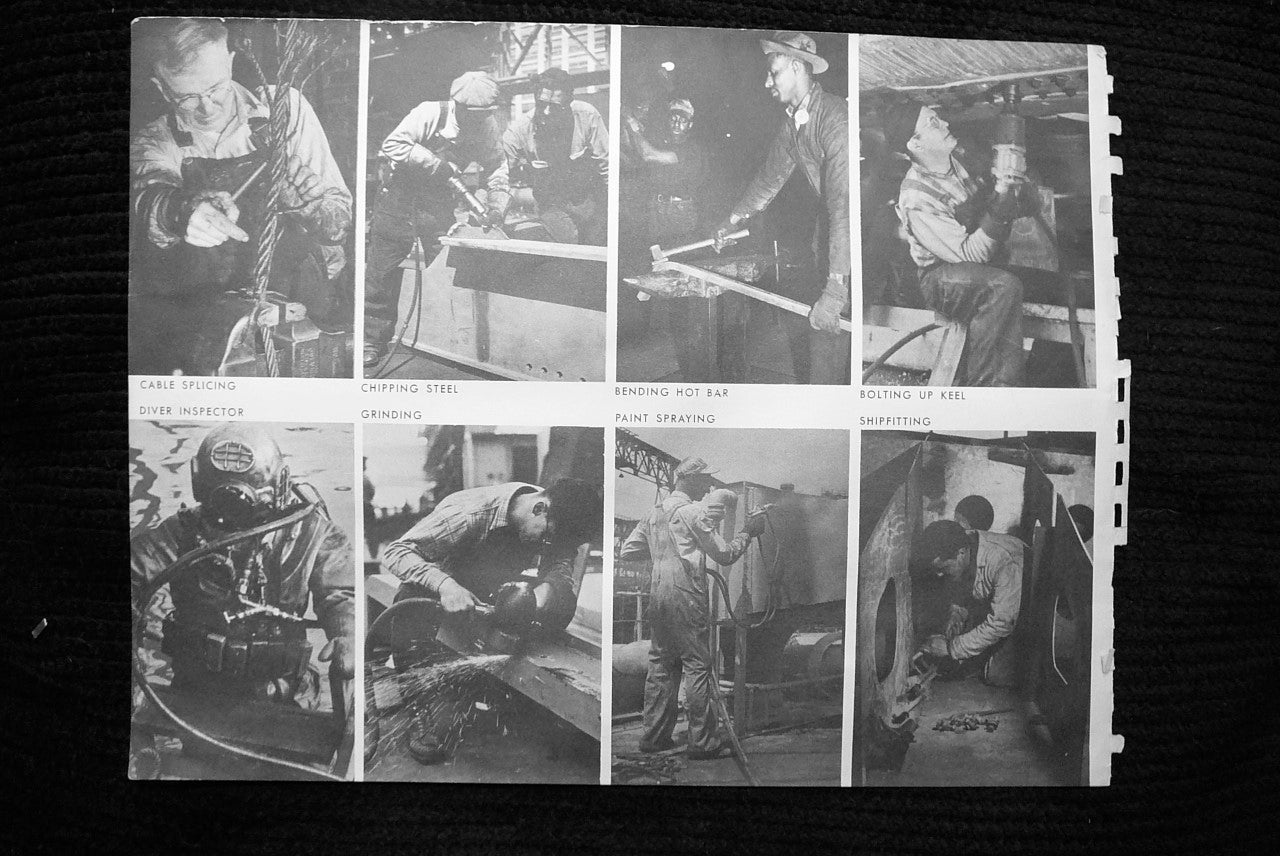

The 460-foot long, 70-foot high building, with its steel skeleton and brick skin, went dormant for 18 years before springing back to life during World War II as a turret shop. In the light brought in through multiple panels of windows that made up the M-shaped butterfly truss roof, teams of men and women built big guns for naval ships.

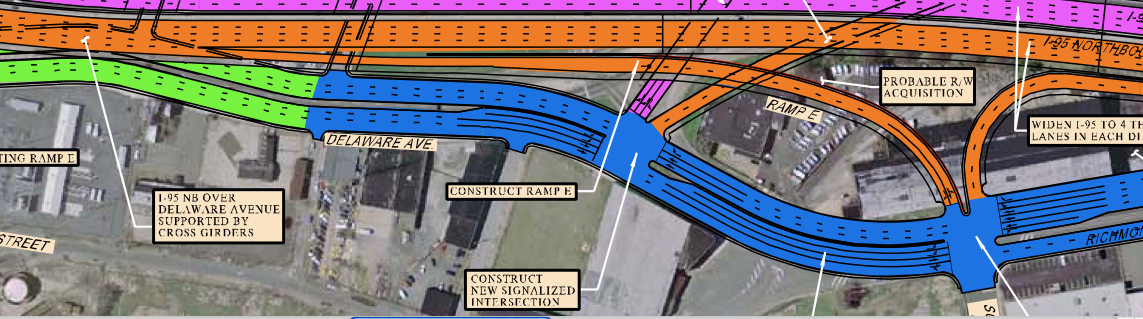

But soon – as early as this spring – this last vestige of Philadelphia’s famous shipbuilder will be demolished to make way for the new Girard Avenue Interchange of I-95.

Its fate has been sealed for years. The Federal Highway Administration gave preliminary approval to the plan that places the spaghetti pattern of ramps where the building stands in June 2003, said Elaine Elbich, PennDOT project manager. The preliminary OK meant that the FHWA was fine with the plan, so long as PennDOT got environmental and other approvals. PennDOT did, and final approval was granted in 2008.

In late 2002 or early 2003, Joel Assouline, then a Philadelphia-based developer, and his wife Vibeke Lichten, an architect and artist, bought the property with hopes of turning it into live-work condominiums.

Assouline knew he wanted to buy the building the first time he saw it. “It has an incredible light. It has this butterfly roof that is just mind-boggling. When you look at it, and you see the engineering that went in there …you couldn’t build a building like that today.”

Assouline said he found out about PennDOT’s plans soon after he bought the building, when he took his ideas to convert the building to condos to the Planning Commission.

“We went and spoke with PennDOT a numerous amount of times,” he said. He asked that the state consider a different route, but was told that wasn’t possible, he said. “Their answer was they had already done the studies, and it would take too long to redo the studies, and that would slow down their project,” he said.

The building remains structurally sound. Some windows are broken, and there is a good amount of detritus – paper, old office chairs, a kid’s bicycle – inside. Since the end of World War II, the building has been used primarily as a warehouse. A sign bearing the name of a dollar store that used it for this purpose still hangs outside.

Preliminary studies to determine what highway improvements were needed began in the mid 1990s, PennDOT spokesman Gene Blaum said, and, with federal approval, the engineering studies that determined exactly how those needs would be met began in the summer 1999.

The Cramp building – also known by its original name that references a Cramp’s subsidiary, I.P. Morris Co. Machine Shop No. 2 – was taken by eminent domain in May 2009, Assouline said. But he said he knew he had lost the fight in 2006. That is when he and his wife moved to New York, where they continue to do re-use and infill projects.

PennDOT needs to take down the building, said Elbich and Monica Harrower, PennDOT District 6 cultural resource professional, at a recent meeting with PlanPhilly. But the state agency is also taking steps to preserve the building’s legacy, they said.

Martin B. Abbot, an architectural historian with PennDOT consultant URS Corporation, has done historical research on the building, and also documented it through photographs and a video – some of which are posted with this story.

Beyond that, portions of the building will physically remain in the city, Elbich said. Some of this will be guided by the Sustainable Action Committee, an assemblage of representatives from neighborhood associations and other groups that represent areas along the project area, the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation, the Central Delaware Advisory Council, and city departments.

Elbich said bricks may be used in landscaping, window sashes could be transformed by industrial artists or used as trellises for greenery. Parts of the enormous cranes that remain inside the structure could be re-purposed as benches, she said.

The demolition contractor will be told to save “More than what we think we will need” based on feedback from the Sustainable Action Group, Elbich said, in case other uses come up later. PennDOT has also asked the city if they want any materials.

Bids for the demolition job will go out within months, Elbich said, and materials that are not claimed locally may be either salvaged or recycled by the contractor. In exchange, PennDOT may pay less for the work, she said.

The loss of the Cramp building was lamented at a June meeting on the Central Delaware Waterfront Master Plan, and the city’s top planner – Deputy Mayor and Planning Commission Executive Director Alan Greenberger – said that the loss of it showed how important it was that the master plan take steps to protect other important waterfront sites, including the Delaware Powerplant (PECO substation) near Penn Treaty Park.

That work is underway, said Master Plan Manager Sarah Thorp, who works for the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation. Historic Preservation Specialist Emily Cooperman and archaeologist Katherine Woodhouse-Beyer have been researching records, studying old maps and driving the Central Delaware to compile a list of historically significant buildings and places that could potentially yield rich artifacts from Philadelphia’s industrial, colonial or pre-historic past. Their preliminary work has been shared with those drafting the master plan, Thorp said, and their final report is expected in about a month.

Informed by their work, the master plan will identify areas where the original shoreline still exists – and note that, depending on whether a project gets government funding, lots of archaeology may be required to develop that parcel. It will also identify buildings that should be preserved in some way, Thorp said.

While that preservation work won’t be part of the master plan itself, Thorp said, it will outline the work that DRWC and interested neighborhood groups should take next: Nominating buildings for the Historic Register. In addition to the PECO station, Greenberger said he certainly wants to see Piers 38 and 40, and the the huge dumper adjacent to the Conrail property preserved. “It is quite fantastic,” he said.

Getting landmark status is a significant step that means alterations or demolition cannot take place without due process, Greenberger said. But, he added, it does not guarantee preservation, as the Philadelphia Historical Commission’s recent permission to demolish the Church of the Assumption on Spring Garden Street shows.

Even if PennDOT weren’t tearing down the Cramp building, Greenberger said, saving it would not have been easy or cheap.

That doesn’t mean such buildings can’t be saved with the right idea and the interest of the right financial backers, he said. The new Tate Gallery in London – an example of possibilities also cited by Assouline, the developer who wanted to transform the Cramp building – is on old power station. And in Baltimore, a power station was transformed into a key part of the Inner Harbor. The new Tate opened in 2000. Assouline visited in 2010, and the structure remind him very much of the building he lost in Philadelphia. “It just made me feel so sad,” he said. “I personally feel that I lost a terrible opportunity, and also that Philadelphia lost an opportunity.”

But even though Greenberger has never been inside the Cramp building, he knows what it is like – and how hard it would have been to preserve – from experience.

When still in private architecture practice, he devised a plan to convert a similar, but smaller building – a power station for the Allentown trolley system – into a museum.

“These buildings are amazing cathedral-like spaces of industry,” he said. “When you go in them, they take your breath away.”

It is no coincidence that entering the Cramp building or the Allentown trolley power station feels so much like entering a house of worship, Greenberger said. While industrial buildings were designed to facilitate work and houses of worship to inspire awe, they used similar means to achieve different ends: Height and light.

Cramp was built with a soaring ceiling to allow for shop work on a grand scale, said local historian Torben Jenk, who specializes in industrial history. The copious supply of windows flooded the floor with light, making detail work easier, Jenk said. And the ventilation those windows provided made workers more comfortable in air that was filled with metal dust and vapors from industrial lubricants.

It is the grand scale that in part makes both kinds of buildings so hard to reuse, Greenberger said.

When granting the right to demolish the Church of the Assumption, the divided historical commission cited the cost of restoration and upkeep on the building.

And something similar happened in Allentown, Greenberger said.

After about two years of work, plans were presented to the board of the America On Wheels Museum, Greenberger said. But “it came unglued because of the cost,” he said. The museum board decided it would cost too much to heat, cool and maintain the former trolley station. And it would have cost between 10 to 20 percent more to renovate the building than to build a new one, Greenberger said. That’s what the board did. The museum Greenberger designed in an “industrial chic” style opened in 2007, he said.

The trolley system building is still there, Greenberger said. “But no one has any idea what to do with it, and unless somebody or something comes along, I imagine it will be torn down eventually,” he said.

Contact the reporter at kgates@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.