Here’s mud in your eye: Whiskey decanters warp historic masculinity at Philly’s Museum of the American Revolution

John Wind’s kitschy send-up of Revolutionary War heroes pokes holes in the masculine image at the Museum of the American Revolution.

John Y. Wind made a sculpture out of a decanter shaped like Baron von Steuben, a Prussian officer who played a role in the American Revolution. The historical record suggests von Steuben lived openly gay. (Peter Crimmins/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

John Wind’s sculpture, “Whiskey Rebellion,” now on view at the Museum of the American Revolution, is triple-aged.

The first rebellion — the one in American history books — happened in 1794 after the newly minted U.S. federal government imposed its first domestic tax on whiskey. It didn’t go over well. A violent insurrection arose in Western Pennsylvania, which quickly diminished.

The second rebellion was in the mid-20th century when distillers like Jim Beam sought to avoid taxes by packaging bourbon in novelty decanters.

Distillers could defer taxes by aging bourbon in bonded warehouses for up to eight years. In the 1950s, the whiskey industry was losing market share to vodka and found itself with a surplus of unsellable product. Facing the inevitable evaporation of whiskey idling in warehouses — the so-called “angel’s share” — coupled with the looming eight-year tax burden, Jim Beam needed to unload lots of bourbon quickly.

Packaging the drink in decorative decanters advertised as collector items worked like a charm. Over the following decades, Jim Beam and other distillers developed thousands of unique designs across a dizzying range of subjects, including Revolutionary War heroes.

“That was the second Whiskey Rebellion,” Wind said. “My Whiskey Rebellion is putting my 21st century self into dialogue with these historical figures, challenging their heroism.”

“Were they heroes based on my own values and what I think is important today?” he asked.

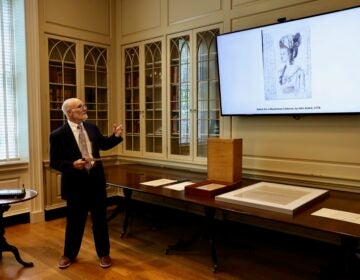

“Whiskey Rebellion” is on view at the museum through June. On Saturday, June 22, Wind will speak to visitors and show off his method of transforming vintage decanters into contemporary art pieces. As a Pride Month event, he will be joined by the Philadelphia Freedom Band marching ensemble, an orchestra of gay and lesbian musicians.

Wind gained access to an extensive collection of vintage novelty whiskey decanters through his fiancé, who leveraged a personal connection to an estate collection of about 300. He uses a hodge-podge of keychains, lapel pins, jewelry charms, stacked books and CD jewel cases to make statements not originally intended by the decanters.

The bourbon industry targeted the decanters to the male demographic and their mid-century man caves: cars, soldiers, hunting. Wind, a jewelry designer, accessorized those male figures to complicate their meanings. The Revolutionary War decanters on view proclaim messages of abolition, gay pride, feminism, self-care, and environmentalism.

The centerpiece is a figure of Baron von Steuben, a Prussian officer known for turning the Continental Army into the superior fighting force that won the Revolutionary War. Seated on horseback, Steuben holds a rainbow-colored gay pride flag and wears an AIDS activist pin, “Silence=Death.”

The historical record suggests Steuben, a war hero, was indeed gay and lived somewhat openly.

“Doing this kind of work, reclaiming my place in the American story, relating to history and personalizing it has been a really cathartic experience,” Wind said. “My hope was, by making it lighthearted and having that sense of humor throughout, other people can also find a way into what’s otherwise very forbidding.”

Museum president and CEO Scott Stephenson concurs that history museums can seem off-putting to some. Giving artists permission — and even encouragement — to take creative liberties with the way history is traditionally presented opens the door to more visitors.

“Not everything has to be grounded in authenticity, as long as you’re clear with your visitors about what you’re seeing,” Stephenson said. “This is the response of a contemporary person who is reflecting back on history and using it in a very clever and thoughtful way,” Stephenson said.

“I was 10 years old when the Bicentennial began, and I remember these decanters around. My dad had a couple of them. You remember them in the gentlemen’s rooms in your neighbor’s houses,” he said.

Baron von Steuben likely did not flaunt his sexuality, support gun control or proclaim “I Believe Her,” as Wind suggests in his assemblage. But the Museum put together a nearby display about Steuben’s relationships with prominent men in Europe and his aide-de-camps on the ground in the Revolutionary War, then poses the serious question: “Was Baron von Steuben Gay?”

“We are interested in presenting history through questions and evidence,” Stephenson said. “We offer the evidence and ask you: What do you think based on the evidence that we present?”

Wind used to be partial to vodka, which was the marketing problem Jim Beam tried to solve 70 years ago. But after a few years of working on his whiskey decanters, he finds himself leaning toward bourbon.

“Now I’m part of the solution,” he laughed.

The fifteen adorned decanters of “Whiskey Rebellion” will be on view until June 30.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.