What’s in the chirping, translucent orb? It’s you.

“Synesthesia” is an experiment in designing spaces that respond to you. After Philadelphia, it heads to the Venice Biennale of Architecture.

Severino Alfonso (left) and Loukia Tsafoulio are the creators of Synesthesia, a work of art exploring the interface between humans and machines, on exhibit at HOT*BED gallery in Old City. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

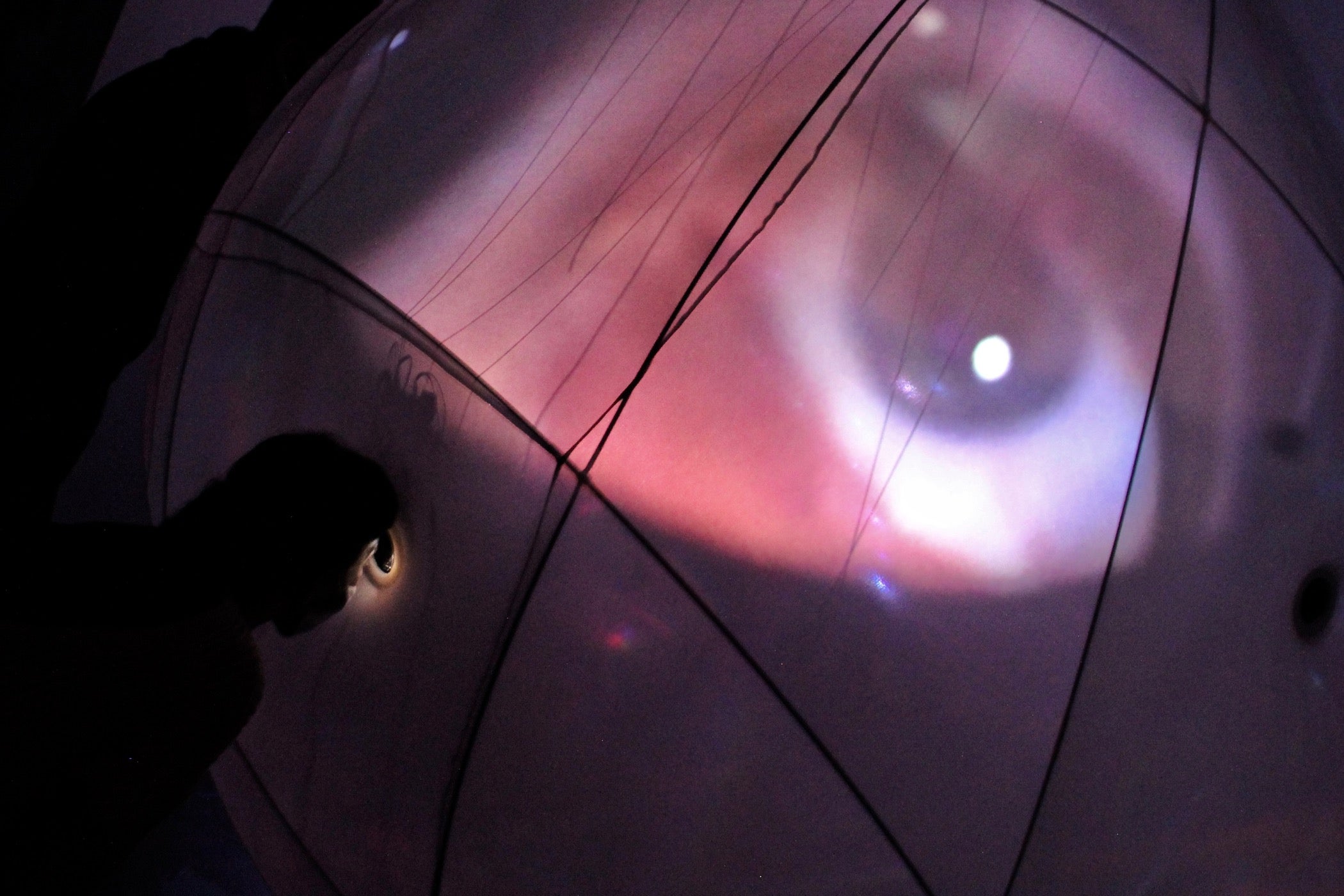

It’s a blob. It’s a brain. It’s a misshapen tent. It’s an artificial, cybernetic alien monster that lures you toward it, so it can steal parts of your body.

“Synesthesia” is a multisensory, interactive sculptural piece taking over the third floor of HOT*BED, a gallery space in Center City Philadelphia. Created by the Synesthetic Research and Design Lab at Thomas Jefferson University, the piece is on its way to the European Cultural Center 2021 Venice Biennale Architecture later this year.

The spherical object glows from within, emitting synthesized electronic pulses, tones, and washes. If no one is near it, it calls out with an inviting chirp to let you know it is waiting for a visitor. Once you get close, it emits a series of grinding sounds.

“The sound experience is meant to be at one moment annoying, and at other moments very compelling,” said co-designer Loukia Tsafoulia. “Sometimes you want to hug it, and sometimes you want to move away from it.”

The piece, about nine feet across and nine feet tall, is meant to be a kind of cinema space where the movie watches you. Its surface is outfitted with several ports that let you peer inside. Some of those ports are outfitted with cameras that take video of your eyeball and project it in real time on the skin of the object.

“That’s the main experience: a central node of multiple projections,” said the other designer, Severino Alfonso. “You move around it, so it forces the idea of a sphere. But we don’t want a sphere. We want to deform it and make it a weird alien form.”

Alfonso and Tsafoulia say the object figuratively “steals” your body parts by filming your eyes and incorporating them into itself. If several people interact with the object at once, all of their eyes merge on the surface of Synesthesia.

“It’s a beautiful fusing moment where … your body part, and my body part becomes one. It’s more of a symbolic understanding of shaping something collectively,” said Tsafoulia.

Alfonso and Tsafoulia founded the Synesthetic Research lab at Jefferson a year ago, as a way to investigate the relationships between humans, built environments, machines, and how all three of those factors can be designed to respond to one another.

“We’re using devices nowadays where there is an intimate relationship, but it’s not very visualized,” said Tsafoulia, who is thinking about Fitbits that monitor our bodies, cell phones that collect our personal data, and Alexa-style smart speakers that listen to us all day. “This projection component makes very visible those relationships we daily construct with our devices,” she said.

Despite its name, “Synesthesia” has little to do with the neurological condition where one sensory stimulus can trigger another, unrelated sense: for example, a synesthetic person might be able to “hear” colors, or “taste” sound. Rather, the designers are using the name symbolically to describe a single object that both triggers and responds to overlapping layers of sensory input and output.

The Synesthetic Research Lab is piggybacking on early cybernetic experiments from the 1940s and 50s, when scientists started considering how nascent computer technologies of the time might be able to more closely mimic the activities of human brains. An informal association of such researchers, the Ratio Club in England, would gather regularly over dinner to share ideas. Alan Turing, considered the father of computer science, visited the Ratio Club a few times to present his ideas about artificial intelligence.

Tsafoulia and Alfonso are bringing those concepts into the architectural field, using these early concepts of computer science and artificial intelligence into the design of built environments that are able to respond to their inhabitants. Right now it’s purely conceptual, but Alfonso can imagine applications in hospitals where people experiencing high-stress psychological episodes might be able to enter a “cool-down” room. The room could be outfitted with machinery that could detect physical and mental states, then adjust its own environmental stimuli to calm down patients.

“Synesthesia” is designed mostly to be a curiosity, a gallery experience that might attract or repel viewers based on their preferences. Part of the experiment is to see how people of different backgrounds react to responsive technology. Currently, Synesthesia does not save any of the information it collects about it’s participants, but its creators are leaving that door open for the future.

“By documenting those interactions, we may create a cultural project, maybe giving us anthropological information about how people respond to these works,” said Tsafoulia. “What does it mean to apply similar experiences to different people?”

Although Synesthesia takes up a lot of space in a room, it is built as a semitransparent skin stretched over a collapsible structure. As such, it can be broken down into smaller parcels and shipped almost anywhere. After it comes down at HOT*BED, on March 6, it will be installed at the European Cultural Center 2021 Venice Biennale Architecture until November. What happens after that is not yet known, but Tsafoulia imagines it can be set up in places where people of diverse backgrounds might interact with it to see what happens.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.