What should a monument be? Here’s what Philadelphians said

After last year's citywide exhibition of 20 temporary monuments, the Monument Lab issues a report on what the public wants.

What is an appropriate monument for the current city of Philadelphia? The Monument Lab project has released its report after years of public engagement and experimentation. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Last fall, several thousand Philadelphians contributed to an experiment in collective memory. The Monument Lab asked 20 artists to create large, temporary monuments in parks and squares across the city, and asked people passing by for their ideas about what would make for an appropriate public monument for Philadelphia.

The ideas ranged widely: from the whimsical (at least 20 involve a pretzel), to the weird (a statue of Elon Musk); from the serious (35 proposals to memorialize the 1985 MOVE bombing) to the entirely possible (a statue of abolitionist Lucretia Mott).

Released Monday, “Report to the City,” summarizes all of the ideas and attempts to draw some conclusions. A searchable online database of the ideas is available at proposals.monumentlab.com.

The report shows many people are interested in memorializing a more diverse range of people. In particular, figures of women, of which Philadelphia – a city full of memorials – is woefully short.

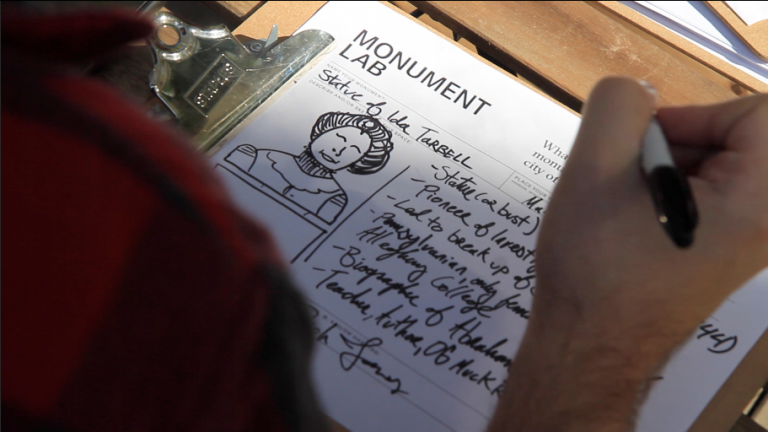

People were also eager to lift up historical figures that are not household names, like African-American architect Julian Abele (who designed the Art Museum) and pioneering investigative journalism Ida Tarbell.

“Philadelphians possess a vast knowledge of the city’s history,” said Monument Lab director Paul Farber, “both in what has been elevated, but also what has been forgotten or what has been cultivated at a neighborhood or community level for some time.”

The public feedback portion of last year’s Monument Lab was designed to be as open-ended as possible. Participants were given little more than a blank piece of paper with only two prompts: What would a memorial pay tribute to and how?

Farber wanted people to freely imagine. That brought back some truly odd, indecipherable suggestions, and some strokes of genius. Taken together, they form a snapshot of the city, a kind of peek into the id of the collective Philadelphian.

The classic monument is a figure carved in stone, staring off into the distance. The report shows people are thinking less about singular heroes and more about memorializing groups of people.

Many proposals involved multiple figures holding hands. Farber is hard-pressed to find any instance of such a thing existing. He was surprised that so many individuals, independent of each other, invented a monument concept that does not widely exist.

“Just from an art historical perspective, the monument of two people holding hands is not something inherited from public space,” he said. “But that hunger to find ways to mark profound challenging histories, and come up with new forms of representation, speak to the spirit of many of these proposals.”

The image of people holding hands is a socially rich one: The act of holding hands implies a divide – a gap – between people. To identify a social divide, and suggest a way to bridge it, would make for a compelling monument.

“Rather than trying to tell us a single story about our history, the monument can be a perch or a platform to understand the complex relationships that bring us together, that push us apart, and challenge equity and equal opportunity,” said Farber.

Last Friday, Farber presented the report to Mayor Jim Kenney and city officials. The report will be printed as a newspaper and distributed to public libraries.

Monument Lab is trying to expand its experimental public engagement model to other cities. With the help of a grant from the Surdna Foundation, it is now rolling out “Remediate,” a program to identify and support artists and activists in other cities who are rethinking how to memorialize community history.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.