What I learned when Kamala Harris came to my block

Columnist Solomon Jones shares his thoughts on what it will take for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris to win the 2020 election.

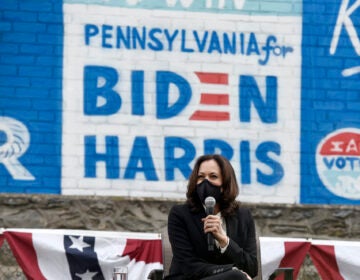

Kamala Harris speaking with Solomon Jones during a visit to Philadelphia on Thursday. (Courtesy of Solomon Jones III)

On Thursday, Democratic Vice-Presidential Nominee Kamala Harris came to Philadelphia, and in a surreal twist of fate, my block was one of the stops on the campaign trail.

But it wasn’t the time that she spent on my street that told me the most about Harris. It was what happened in the hours before.

Around 10:50 a.m., as I rushed home from work, I rode past Relish restaurant on Ogontz Ave., near Walnut Lane. There, I noticed a plethora of campaign signs taped along the parking lot’s gate. Counter-terrorism police were posted on the corner, and the mayor’s security detail was lingering out front. Knowing that Relish often hosts political events, I surmised that the restaurant was one of the stops on Harris’s tour. I stopped, and learned that I was right.

It was shortly after 11 a.m. when Harris’s motorcade arrived. I watched as two white men pulled up in a car across the street. They parked with flashers on and exited the vehicle. One of them yelled, “F— Kamala Harris!” as his comrade watched silently. “She’s not African American!” the man shouted. “She’s Asian! F— Kamala Harris!”

A nearby police officer wondered aloud if the men were members of the white supremacist group, the Proud Boys. A passing Black motorist might’ve had the same impression. As the white man once again yelled “F— Kamala Harris!” the motorist yelled, “F— you, too!”

Those weren’t the only angry moments I witnessed. As Harris walked down the street amid a throng of campaign staff, Secret Service agents and press, a Black man stood in the doorway near State Representative Isabella Fitzgerald’s office. He was grumbling that Harris and Biden wouldn’t change anything. He was angry that Harris, a former prosecutor, had played a role in jailing Black people. A campaign staffer walked up to the man and asked if he wanted to speak to Harris. He said no. She stopped to speak to him anyway.

I couldn’t hear the whole exchange, but I heard him tell her that too many Black people were jailed. She told him that would change. His body language said he didn’t believe it, and as he stood there and talked about not voting, a little boy stared up at him, soaking in every word.

I was impressed that Harris took a few moments away from the adoring crowd to talk to him, and that even though he wasn’t swayed, she made the effort. That short exchange with a disgruntled man illustrated a larger point for me.

Biden and Harris aren’t just running against Donald Trump. They’re running against cynicism, against hopelessness, and against a history that says no matter how well Black folks do, we’re always swimming upstream.

Convincing Black people who’ve repeatedly experienced political disappointment to vote in big numbers is the challenge. If Biden and Harris can do that, they will win, but doing so will require tough conversations. It will require listening.

By 1:23 p.m., Harris’s motorcade was arriving on my block to the sounds of cheers. She was there for a women’s event hosted by my neighbor, Philadelphia City Councilmember Cherelle Parker. The event, which was tightly controlled by the Biden-Harris campaign, was an opportunity for Black women to hear from Harris. But even as I watched my community respond to Harris with adoration, I knew that the Biden campaign would ultimately have to respond to the cynicism. So, when I had the opportunity to do so, I asked Harris the one question that Black voters will need answered in the days leading up to the election.

“There’s a lot of enthusiasm here today,” I said in reference to the cheering crowd who surrounded us we spoke. “I talk with the Black community every day. One of the things I hear often is ‘What is the difference between Joe Biden-Kamala Harris and Donald Trump?’ From a policy perspective, how would you answer that question?”

“Everything,” Harris said, prompting a chorus of agreement from those within earshot.

“Why are we all wearing these masks?” she continued. “Because we’re in the midst of a pandemic, which six million people have contracted. Almost 200,000 people have died. Black folks are three times as likely to get it, twice as likely to die from it. We now know Donald Trump knew about the seriousness of this back in January. In February — we don’t even have to hear what he told somebody. We heard the tape. He knew it was lethal. He knew it was airborne and he said it was a hoax. He said that it wasn’t serious and people are dying from it and our folks are dying in particular. Everything is different.”

Harris then began to tick off a series of policy initiatives that are tailored to address the needs of African Americans.

“We’re talking about what we need to do around funding HBCUs,” she said. “I am a proud graduate of Howard University. We intend to put $70 billion into our HBCUs because we know that’s the pipeline for so many of our national and international leaders … Access to capital. I’ve been here to Philly visiting all the small businesses. Ninety percent of the businesses in Philly are small businesses. Almost half of which are Black-owned. We are going to put $100 billion into low-interest loans targeting Black and brown small businesses to get access to capital so we can continue knowing our small businesses have always been a part of the economic lifeblood of our community. Our small business leaders are not only business leaders, they are civic leaders, they are community leaders. These are just some things of the … many things that we will do.”

People cheered as she walked away, moving on to shake more hands. However, those aren’t the people the Biden-Harris campaign will need to reach. They will have to find an answer for the cynics, and if they can do that, they can win.

Your go-to election coverage

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.