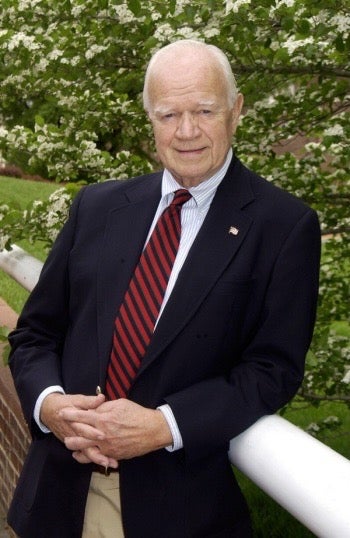

Wayne Craven, 89, ‘Dean of American Sculpture’ and ‘traditional gentleman’

U. of Delaware professor Wayne Craven left behind a long list of former students who are now experts on American art, and a mark on the study of art history.

Listen 2:58

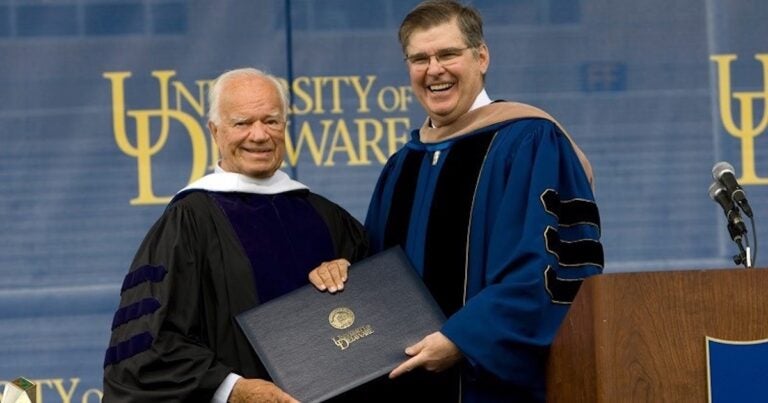

Wayne Craven (left) received an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from Board of Trustees Chair Howard Cosgrove at University of Delaware's 2008 commencement ceremony. The citation called Dr. Craven a 'champion of American art' and a 'fluent and graceful teacher.' (University of Delaware)

This story is part of WHYY’s series “COVID-19: Remembering lives we’ve lost” about the everyday people the Philadelphia region has lost to the coronavirus pandemic, the lives they lived, and what they meant to their families, friends and communities.

Roberta Tarbell’s most vivid memory of her former professor Wayne Craven is their first encounter in 1965 — an interview to determine her acceptance into the University of Delaware’s art history graduate program.

Wayne leaned back on his office chair, puffed on his pipe and said; “This is highly unorthodox, but I want to accept you as a graduate student,” she recalls.

Roberta had only taken one art history course during her time at Cornell University. But Wayne told her if she registered for some art history courses over the summer, he would take a chance on her.

The words of encouragement were refreshing after a department chair at another university said she wasn’t qualified, and her area of interest “wasn’t art.”

“The chair of another department said, ‘There’s no chance, and there’s no place in the field for women, and you want to study American art — and it isn’t art.’ But [Wayne] was saying, ‘We’ll work with you,’ and he did,” said Roberta, now a professor emerita of art history at Rutgers University, and visiting scholar for the Center for American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

She said the encounter is all encompassing of the kind of man Wayne was — someone who encouraged his students to go after their dreams. It reflected his own drive to put American art history on the map in the mid-to-late 1960s, during a time when many academics deemed it unworthy of study. Although almost no one had studied American sculpture, Wayne followed his passion and eventually became known as the “Dean of American Sculpture.”

Wayne, of Newark, died on May 7 at the age of 89 following a bout with COVID-19. He overcame the virus, but not long after he was released from a hospital, died at home from heart failure.

He left behind an academic legacy, and a long list of former students who are now experts on American art. Wayne’s former colleagues and students remember him as an elegantly dressed, traditional gentleman, known for his keen sense of humor, and for his willingness to offer both academic and emotional support.

“He was always elegant, always kind and always had his door open,” said former student and colleague Joyce Stoner, a professor of material culture, and the director of the preservation studies doctoral program at UD.

‘A brave choice’

Known as a devoted researcher up until his death, the award-winning professor and nationally known scholar wrote numerous books and articles on American art. His first book “Sculpture in America” is considered one of the first of its kind, and his book “American Art: History and Culture” is a classroom standard.

“In the mid-century, sculpture was thought to be unoriginal — especially the human figure form, which was not thought to be a stroke of artistic genius, but an artisan making reality,” said Wayne’s goddaughter Kate Lemay, a historian at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery.

“Scholars are now interested in sculpture,” she said. “We think sculpture makes architecture and spaces, and punctuates memories in ways that other things don’t. A painting by necessity is stored indoors, whereas a sculpture is accessible to everybody.

“Wayne was the first one to put this information pen to paper. At the time, you were just so gauche if you went to that kind of topic for a subject for research. It was a brave choice to do it.”

Wayne received his PhD in art history from Columbia University at a time when American art history wasn’t taught. His specialty was medieval art, but he developed an interest in works made in this country when he became part of a small group of art history professors at UD in 1960. Six years later, he and the late William Innes Homer launched the university’s Art History Department.

“He would casually agree with any outline we had; as soon as we had a bright idea, he would say, ‘Go for it,’ and he was enthusiastic,” said Roberta Tarbell, who also is an adjunct professor of art history for the Winterthur Museum/University of Delaware Preservation Studies Doctoral Program.

Many of Wayne’s students have since been hired as American art curators and directors at renowned museums across the country, and have published countless essays, books, exhibition catalogues and grants.

“I think he was the advisor to more than 30 dissertations, so he informed and propelled an army of scholars in the field,” Roberta said.

Wayne’s colleagues and former students say despite his success, he remained humble. He volunteered to teach one of the largest courses at UD every year, which enrolled as many as 350 students. Colleagues say many senior faculty at various universities prefer to focus on research and writing for the professional rewards. But Wayne, who loved teaching, found time to do both.

Joyce Stoner met Wayne as a colleague when she began teaching at UD in 1982, but became his student while working on her PhD in art history in the mid-80s. She recalls that when she began work on her paper “Washington Allston: Poems, Veils and ‘Titan’s Dirt,’” which was later published, Wayne offered her all his files about the artist to aid her research. The act of kindness inspired Joyce to be a supportive professor.

“I’m always trying to be the same way — of not thinking, ‘I’m not going to share this, maybe this person will go off and publish it before I do.’ He wanted to give the best possible leg up to any of his students,” said Joyce, also a paintings conservator for the Winterthur/UD Program in Art Conservation.

The only thing that rubbed him the wrong way was tardiness, Joyce said.

“I think two or three people were late in this one particular class, and he got quietly red-faced and went to the back of the room and locked the door and said, ‘There will be no more latecomers!’” she said with a laugh. “He was very traditional, and very upstanding and wanted people to obey the rules, and be on time and be polite and not interrupt, that sort of thing.”

Show your support for local public media

A ‘traditional gentleman’

Colleagues and loved ones describe the professor as a “traditional gentleman” — from his well-mannered behavior, to his habit of hand-making Christmas cards every year, to hosting his friends at his house for pre-dinner cocktails, to his elegant sense of style.

One year, Wayne won a student-voted “best dressed faculty member” award, for which he was both “pleased and a little embarrassed,” said Lawrence Nees, a colleague since 1978.

“He was always quite nattily dressed,” he said. “I think it was his way of showing his respect for his students; that he would be as formally attired in addressing a group of undergraduates as he would be meeting the president of the university — or going to the White House, which is something he did because of his expertise in American art.”

Wayne’s office was just as immaculate as his attire.

“There was one year where Wayne served as acting chair during my time, and all my other chairs were somewhat like me; you go in their office and there’s stacks of papers everywhere waiting to be handled — Wayne’s desk was clear,” Lawrence said.

His Type A personality also gave way to a playful and “devilish” sense of humor.

“He would say something absolutely straight-faced that seemed completely outrageous, and was deliberately so. He was pulling one’s leg,” Lawrence said.

Kate Lemay, whose father was an English professor at UD and Wayne’s best friend, said her godfather used his humor to help those he cared about overcome difficult times. Kate remembers growing up, Wayne and her father were devoted friends, visiting each other and their wives every week.

“We had a special relationship. He was a mentor, he was a fatherly figure, he was sort of like an uncle. He was a part of the family,” she said.

Wayne’s great-nephew Max Gosc, who lives in Indiana with most of his family, said he was always kind and generous, and available to lend an ear and offer advice.

“When they came out here for Christmas, we used to bake cookies and decorate them,” Max said. “He was always my go-to person. When I needed someone to talk to, I would call him.”

Wayne also had a deep respect for his wife Lorna, who died in February, Kate said. Lorna had a significant influence on his work, and the pair did research together.

“Wayne and Lorna lived for each other — it was that kind of love. As a young woman, my mom would point to Wayne and Lorna as like the couple,” Kate said.

“Lorna was part of that generation where the woman would support the man. It wasn’t unusual for women to type their husband’s manuscripts. But Lorna was an ideas person, and was a very intelligent, smart woman, trained as an artist. She would consult with Wayne. And I think she was his first brainstormer. She would edit his work and help him. He dedicated every book to her — and men weren’t always generous at this time.”

Wayne published a book as late as 2018, and was still doing research up until this past fall. One of Kate’s last meetings with her godfather was at the library.

“It was so endearing and touching to me that even as an elderly man who had hip problems, so it was hard for him to walk, he persevered and he went to his office regularly,” she said. “What’s important to understand about Wayne is he lived for scholarship. His brain was constantly active and he was always inquisitive and curious and wanting to know more things.”

Joyce agrees: Wayne’s life was devoted to study, and he even consulted on former students’ work after retirement.

“Dedicated people, you can’t stop them, and he was one of those people,” she said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.