‘I’m not included here’: People with disabilities face barriers to voting in Philly and beyond

If as many people with disabilities turned out to vote as those without, then the 2018 midterm election would’ve recorded a whopping 2.35 million more votes.

Elizabeth Clay, a Conshohocken voter with a physical disability. (Courtesy of Elizabeth Clay)

Ask us: What do you want to know about voting and the 2020 election?

Liam Dougherty has abstained from voting before because his polling place was inaccessible.

Dougherty, who lives in Fairmount with a progressive muscular disability, has to navigate an old church at 20th and Brandywine to cast his ballot. For years, Election Day was a struggle, sometimes an impossible one.

“There were times where it was really hard for me to get into the building, or I just did not vote,” said 31-year-old Dougherty.

That changed last year when Philadelphia outfitted all polling places with wheelchair ramps, door stops and wedge mats to smooth out doorway bumps — mostly because they had to roll in those big, new voting machines for the last general election.

But while all polling places are now wheelchair-accessible, challenges remain for Philadelphians with disabilities. Doorways may be compliant with federal American with Disabilities Act rules but the barriers to polling places aren’t limited to the moment of entry, voters say.

There are plenty of other obstacles that people with disabilities face in casting their ballots, like getting to their polling places, waiting in long lines and lowering the voting machines to wheelchair height. And even though mail-in ballots have presented a more accessible alternative, they can still pose a challenge for people who are blind and those who have dexterity issues.

The barriers add up. Voter turnout is consistently lower among people with disabilities compared to able-bodied people. If as many people with disabilities turned out to vote as those without, then the 2018 midterm election would’ve recorded a whopping 2.35 million more votes.

In an already anxiety-inducing election year, the potential for inaccessibility is just another hurdle.

“Someone who’s non-disabled might only have to think about, ‘Well, how am I going to get my ballot, in person or mail in?’” said Elizabeth Clay, a Conshohocken voter with a physical disability. “There are added layers of consideration that people with disabilities have to think about. It’s just an added layer of frustration in that process.”

Roadblocks to the ballot

Clay lived and voted in Philly for 10 years before moving to Conshohocken. Clay is missing her right leg, which makes it extra challenging to navigate city streets and make it to her polling place.

“It was like the job was done kind of halfway,” Clay said. “Many locations try to do their best to make it accessible, but you have to consider how you’re going to travel to the polling place.”

This year, the problem could be even worse. The pandemic has forced the City Commissioners to repeatedly adjust and readjust their list of in-person polling places. Voters can’t be certain of their voting location until 20 days before Election Day, per Commissioners spokesperson Kevin Feeley, which could make it more challenging for voters with disabilities to find a ride on short notice.

And with fewer polling places open, voters might expect longer lines to get inside. That’s a huge problem for Dougherty, whose physical disability includes bladder control issues.

Even inside, it’s a struggle. Commissioners spokesperson Feeley said all poll workers are taught how to modify the voting machines for ADA accessibility, but Dougherty said he’s had problems with poll workers not knowing how to lower the machine to reach his wheelchair.

Jamie Ray-Leonetti, the associate director of policy at Temple’s Institute on Disabilities, has experienced similar obstacles to casting her vote. Fortunately, her polling place is right inside her Center City apartment building.

But when she went to vote in 2016 with her husband, who also has a disability, she found a table in the way of the wheelchair accessible path to the voting machine. She had to ask poll workers to move it — but after they did, Ray-Leonetti said they put it right back.

If she hadn’t been there, she suspects her husband would’ve been so discouraged that he would’ve left without voting.

“It’s like being told that you’re invisible, or that your vote doesn’t matter,” Ray-Leonetti said. “These people who are able to walk and see perfectly and navigate the world around them perfectly, they’re able to get into this location and vote with no difficulty. For me, I get in here, I get off the elevator, and the first thing I see is a table blocking my path. I’m not included here.”

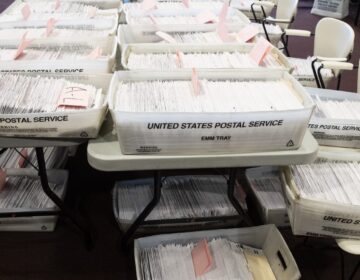

Voting by mail

Many voters with disabilities say that mail-in voting is a huge help. Allowing folks to cast their ballots without leaving their homes is often way more accessible than the alternative.

Clay said after voting by mail twice this year, she never wants to go back to a polling place again.

But even that alternative isn’t foolproof.

Dougherty voted by mail in the June primary. His physical disability imposes dexterity issues. He struggled to fill out the bubbles and write his name and address on the correct lines.

“That’s another factor I’m unsure about,” Dougherty said. “If it’s illegible, I don’t want to get my ballot thrown out.”

There have also been problems for people who are blind. In May, a federal judge ruled that Pennsylvania had to provide a way for visually-impaired voters to fill out a mail-in ballot online, print it at home and then return it to their county elections office.

Katie Maunder, 34, of Collingswood, NJ is blind — and even with the accessibility updates, she said she couldn’t have filled out her mail-in ballot without her mom’s help.

“I honestly wish we could submit it electronically,” she said. “I hope one day it could get figured out so I can vote as any sighted person could.”

How do we fix all this? Ray-Leonetti said true solutions will have to come directly from the disability community. She recommends City Commissioners put together a focus group of people with a variety of disabilities — then have them tour a few polling places before Election Day to point out potential accessibility issues.

“It’s great you’ve made progress, but just understand that things still are not as accessible as they need to be, and it’s a work in progress,” she said. “You have to make sure that what you think is accessible is actually accessible in real life.”

But Feeley said that’s unlikely: “Given the tremendous level of interest in the upcoming presidential election, particularly in these last days, the resources of the Commissioners are being stretched to the limit, and I am not sure that it will be possible.”

Your go-to election coverage

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.