View from the top: Two new luxury buildings welcome the wealthy – and why that matters for the rest of us

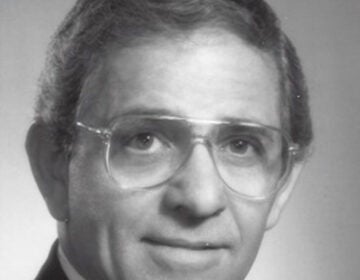

Tom Scannapieco is standing in the penthouse suite of 500 Walnut, his latest addition to the tippy-top of Philadelphia’s real estate market. The building is still under construction and the walls are a raw grey concrete. Caches of tools and building materials lie scattered about the huge room. Men from seemingly every building trade union in the city, and South Jersey besides, swarm almost every floor of the 26-story building.

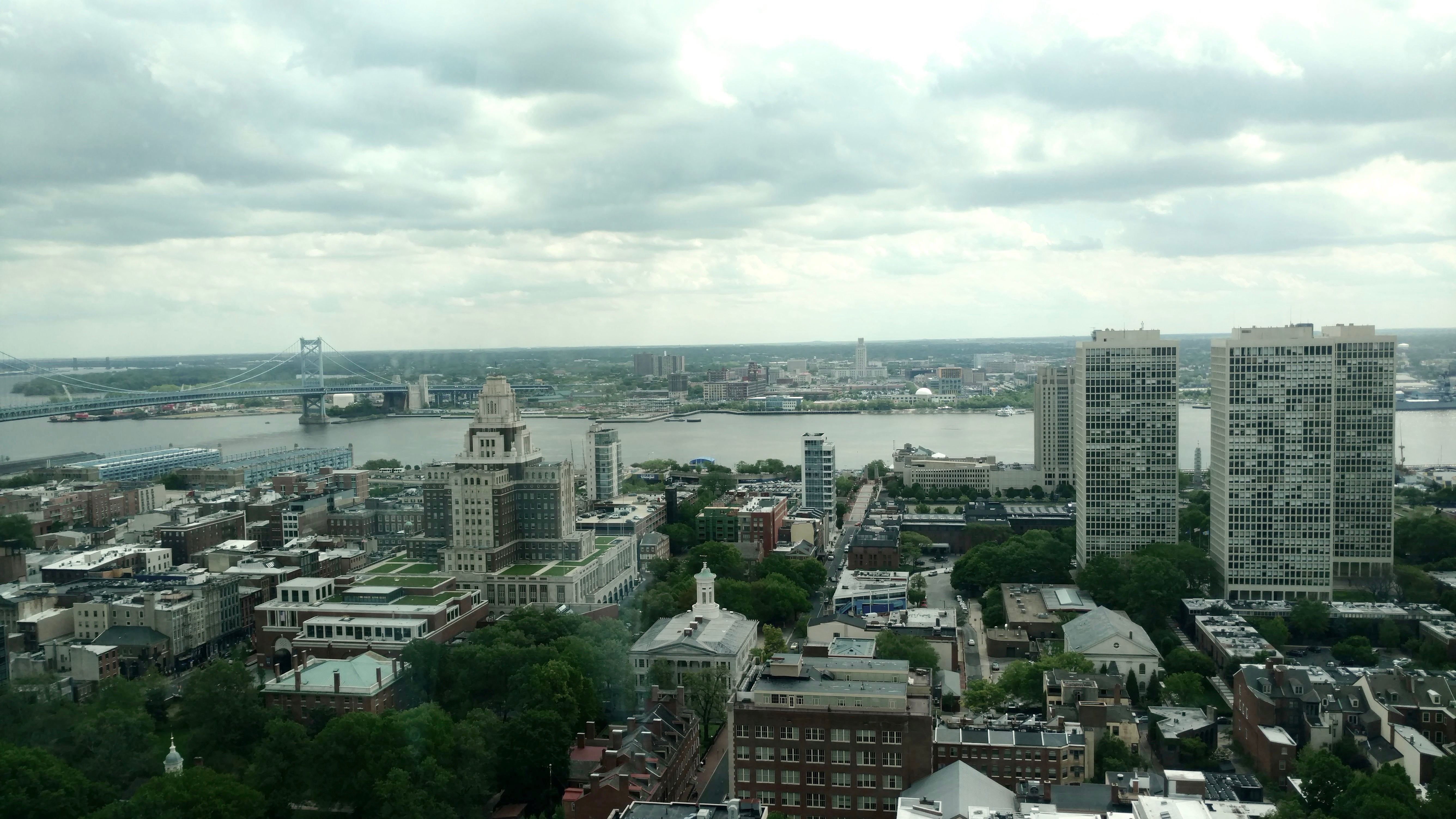

500 Walnut isn’t done yet, but the views are already there to be admired, offering a vision of the city that isn’t usually available this far from the cluster of skyscrapers west of City Hall.

Look out of the easterly windows and see the Delaware River coiling gently around the city, stretching up to the Betsy Ross Bridge in the Northeast and down to the Walt Whitman Bridge in deepest South Philadelphia. The three fingers of Society Hill Towers poke up below, looking rather stubby from this height. Across the river there’s Camden City Hall and an expanse of South Jersey beyond. To the north Independence Mall stretches out, gashed by construction equipment, and then a sea of rowhouses fade off into the blue distance.

Of course the views are this spectacular in a double-decker penthouse suite with its own private elevator. Like all the units in 500 Walnut, there are no interior walls so the space is entirely customizable (all the utilities are in the floors and ceilings). There’s also robotic parking service.

In 2016, when 500 Walnut was still just a rising four-story nub, the then-imaginary penthouse sold for almost $18 million. It was the most expensive housing sale in the history of the city — surpassing the penthouse in Scannapieco’s previous ultra-luxury high rise at 1706 Rittenhouse Square Street.

“We are bargaining for that very, very small slice of the market,” said Scannapieco. “I’m not trying to appeal to a wide range of price points or types of people. And that enabled us to maximize everything. That’s our niche.”

Philadelphia isn’t seeing a boom in this kind of ultra-luxury housing. In fact, Scannapieco doesn’t have any real competition—in the city limits anyway — for new buildings at this price point. The only other new construction within striking distance is Carl Dranoff’s recently opened One Riverside, where prices start at $715,000 and the penthouse is listed at $7 million. 500 Walnut’s prices start at $3 million.

“Most developers would be paralyzed by a building of this size, but not Tom,” said Cecil Baker, the architect for 500 Walnut and One Riverside. “This is a needle tower and the wind pressure, the lateral pressure is so severe. You just don’t see them very often because they are so expensive.”

But in a city with a poverty rate as staggeringly high as Philadelphia, and a median income under $40,000, should the average city resident care about Scannapieco’s needle tower aimed at housing the wealthiest strata? Should one even, perhaps, be irritated by the ten-year abatement on the property that allows its exceedingly wealthy occupants to avoid real estate taxes for the next decade?

Scannapieco is prepared for that question. He’s been in the real estate game for decades, although he only entered Philadelphia proper in the first years of the 21st century when he started acquiring land for 1706 Rittenhouse. Before that, he’d spent his career building and marketing housing in the suburbs (including one ultra-luxury development in Bucks County’s New Hope).

Until recently, that’s where the market that he’s now selling to was almost exclusively based. The fact that the wealthy are taking a greater interest in city living, he says, is cause for celebration.

“This enables Philadelphia to attract a very influential wealthy market that can do things no other segment of the market can,” said Scannapieco. “A lot of our buyers are known for their philanthropy. They are corporate leaders who make decisions about job location, so it’s very, very important for the city to be able to have those types of people live in Philadelphia.”

The negative externalities of ultra-luxury housing in places like Manhattan, Miami, London, and Vancouver are not going to accompany 500 Walnut. Scannapieco’s clientele may “want New York,” but they aren’t the kind of people who have been purchasing ultra-luxury condominiums in Manhattan. Foreign nationals do not see Philadelphia as a market where they can park their capital in gold-plated housing in the sky. There are no Russian oligarchs, Saudi princes, or other foreign nationals buying units in 500 Walnut, says Scannapieco.

Philadelphia is still a regional city, not a world city, and the people who are buying at 500 Walnut and One Riverside are almost all from the area. Scannapieco says that two-thirds of his buyers are moving in from the suburbs and that the final third are moving from elsewhere in Center City. In Dranoff’s case, it’s closer to a half and half split.

“There’s no foreign investment in residential condos in the city,” said Scannapieco. “Philadelphia has a vitality at street level that really differentiates it from other cities in America, but when you are in the shadow of New York and Washington it doesn’t stand out as much. It’s more attractive to the local population that appreciates the quality of life as opposed to the international population looking for something more visible and reputational.”

Largely comprised of executives, business owners, or former business owners— Scannapieco dismisses the notion that 500 Walnut might be marketed to sports players of any description—these are the region’s power elite. For much of the 20th century this class moved, and stayed, out of the city. They tend to choose the historic, wealthy communities of the Main Line, new-money strongholds like Blue Bell, or the stately horse country of Chester County.

Inside the city limits, there hasn’t been much that seemed to interest this very sliver of the market until the early 21st century.

In the late 1990s the annual number of house sales over $1 million in the city could usually be counted on one hand, according to TREND MLS data provided to PlanPhilly from Drexel University economist Kevin Gillen. The biggest year before the crash, between 1997 and 2008, was in 2005 when 69 sales of more than $1 million were recorded. In the fourth quarter of that year alone, the Pennsylvania-side suburbs saw 115 sales of more than $1 million.

“At the beginning of this century, in the whole city there were only five houses for over $1 million,” recalls Councilman Allan Domb, who made his name and fortune as the “Condo King.” “It was really sad. The quality of life and the tax structure did not appeal to high-income people. Now you have a city that’s changed dramatically. Those people want to live here now.”

Domb too is selling units at over $1 million right now, at the Parc building off of Rittenhouse Square. And he isn’t the only one. In 2016, the number of sales over $1 million were the highest they’ve been in at least 20 years with 92 housing units going for that price or more in the city. (Every Pennsylvania-side suburban county clocked more comparable sales, although Philadelphia was very close to the totals racked up by Delaware and Bucks counties. Montgomery County reigned supreme with 161 sales.) City sales in the first quarter of 2017 are higher than in the equivalent timespan of any other year, outstripping every suburban jurisdiction.

In an age of stagnating incomes, temporary employment, and pitchfork populism this uptick of million dollar sales has a PR problem. Life at the top of Philadelphia’s housing market is so remote from the experience of the vast majority of city residents that it’s hard to imagine most people have any positive feelings about it.

But there are many virtues to a diversity of incomes in a city. On a micro-level, there’s the trickle-down effect of wealthy residents spending more of their consumer and dining dollars in the city, and related tax revenues. On a larger level, there’s compelling research that shows wealthy people give more philanthropically when they live outside of wealthy enclaves. The city’s budget will be boosted by the tax revenues from the real estate transfer tax and, after the ten-year abatement expires, from property taxes. Better that City Hall ultimately gets that money than Blue Bell.

“Attracting wealthy households to live in the city has a very strong fiscal benefit,’ says Drexel University’s Gillen. “These households not only pay a lot in taxes, but they also consume much less in public services than poorer households. This results in the city having a lot more money to improve both the quantity and quality of public services for low-income households.”

Scannapieco, Domb, and others in the real estate world argue that there’s another boon for the city in buildings like 500 Walnut. For decades, jobs have fled the city along with the wealthy. If the business owners and CEOs move back, they say, more of the jobs may move back too.

“You can spend a lot of money on subsidizing companies to move into the city,” said Scannapieco. “You can create KOZs [Keystone Opportunity Zones], reduce their taxes, give them government grants for job creation. You can spend a lot of time and effort on that, but if you really want to keep the company in the city have the CEO live in the city.”

If Scannapieco is right, then Philadelphia could use another couple 500 Walnuts. A 2013 Brooking Institute report found that 64 percent of the metropolitan area’s jobs are located between 10 and 35 miles away from its urban centers—that’s a lot of time, money, and gasoline spent to commute in a region with one of the finest transit systems in the nation.

There’s a longstanding narrative in urbanist circles that part of the reason for job flight, especially in the worst years of the urban crisis, was that employment followed CEOs to the suburbs. In the 1970s, William Whyte found that 31 of the 38 companies that left Manhattan one year moved to new locations within eight miles of the CEO’s home. In the words of influential urban historian Kenneth T. Jackson, “the most important variable in determining the direction of a corporate shift was the location of the home and country club of the chief executive officer.”

That’s very much an argument that Scannapieco and other like-minded developers buy into. When the investment firm Equus Capital Partners Ltd announced in February that it would be moving from Center City to Newtown Square, Domb saw it as another example of suburban CEO-syndrome. When he ran into Scannapieco after the announcement, the councilman told him that the city wouldn’t have lost that business if its CEO had bought a unit in 500 Walnut.

There are fears that as the wealthy start to move into the city again, real estate prices will rise and long-term residents will be displaced. While it is unlikely that projects like One Riverside or 500 Walnut are directly affecting prices in, say, Cedar Park there are ripple effects from the larger trend of the region’s richest taking an interest in the city again.

“It is not this cohort of buyers that is directly causing any displacement in the city’s traditional neighborhoods because they are overwhelmingly buying in core Center City neighborhoods,” says Gillen. “But, as they bid up real estate prices downtown, younger and less affluent households are being pushed out to less pricey neighborhoods.”

Among city leaders, many seem to see the upside to this uptick in seriously wealthy residents. On the same spring day Scannapieco looked out over Old City and the Delaware River from the penthouse of 500 Walnut, Dranoff cut the ribbon for One Riverside. The unit count ended up being just 68 rather than the 82 originally planned, as several buyers chose to obtain multiple units and combine them. The building is 80 percent sold. (500 Walnut is two-thirds sold, as of early June, and buyers will start moving in this fall.)

In One Riverside’s courtyard luminaries of the city’s political and development scene, including a third of City Council, milled around snacking on hors d’oeuvres and sipping champagne. The director of planning and development, Anne Fadullon said a few words, as did the city’s managing director Mike DiBerardinis, and District Councilman Kenyatta Johnson.

As the party shifted inside towards the model units and the open bar, DiBerardinis was overheard chatting with a few acquaintances as he sidled towards the exit.

“We can’t only do this, but this kind of thing helps us get the revenue to invest in the neighborhoods,” he told them. Philadelphia can’t only be satisfied with high end growth, the managing director said, but it certainly doesn’t hurt.

“It’s all connected,” said DiBerardinis, gesturing at the condo tower behind him, as he made for the street.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.