Urban agriculture leaders ask for citywide commitments to garden preservation and creation

More than one hundred urban farmers and food justice advocates, some of them with cardboard signs in the shape of carrots, tomatoes, and eggplants, attended the first Philadelphia City Council hearing completely devoted to urban agriculture.

A total of 22 witnesses representing nonprofits, public agencies, students, and grassroots organizations testified to the health, social, environmental, and economic benefits of using vacant lots as community gardens and expressed the need to keep cultivating long-tenured gardens, create new green spaces, and have a say in land-use decisions.

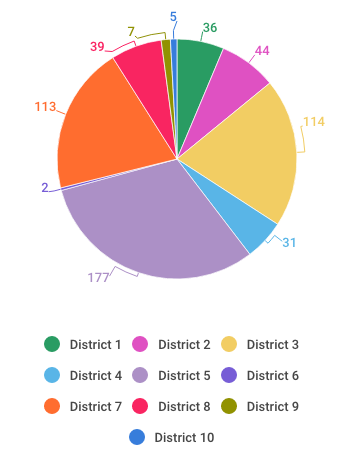

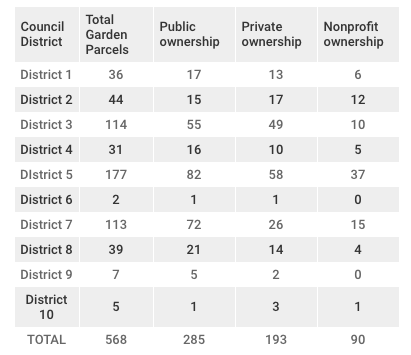

Philadelphia has a long tradition of community gardens and farms and it has become a “national model” in urban agriculture, according to a Scott Sheely, a representative of the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture who testified at the hearing. There are at least 470 gardens on almost 568 parcels in the city, according to the Philadelphia Food Policy Advisory Council (FPAC), but many of the gardeners are in constant fear of losing these spaces because they don’t own or control the land.

“One day we received notice that a privately owned plot of the land on which we gardened, was going up for Sheriff’s sale,” testified Jamilah Meekings, a lifelong resident of the Brewerytown/Sharswood neighborhood and a third generation gardener in the Master’s Work Community Garden at Master and 25th streets. “Unfortunately, we were outbid.”

“That story gets heard again, and again, and again,” Amy Laura Cahn, a staff attorney for the Public Interest Law Center’s Garden Justice Legal Initiative and a Co-Chair at the FPAC, told PlanPhilly after the hearing. “And we yet don’t have an affirmative commitment to preserve these places and to create new ones.”

Urban agriculture leaders applauded the progress the city has made so far, such as the zoning reform in 2012, the FarmPhilly program, the creation of the Philadelphia Land Bank in 2013, and policies like a stormwater fee exemption for gardeners. But as Christine Knapp, director of the Office of Sustainability, said to City Council “we acknowledge the need for a more comprehensive urban agriculture strategy within the city.”

“There’s still this tension that we are trying to debunk: the tension between food production and open space and brick and mortar construction,” Cahn told PlanPhilly. “Those two things are both needed in neighborhoods to create sustainable healthy places for people to live, but there’s a perception of a competition between the two. And gardening, and farming and open space do not win at all. We want to create policies and systems that, in some cases, the decision is made that a garden or a farm is the highest and best use for a parcel.”

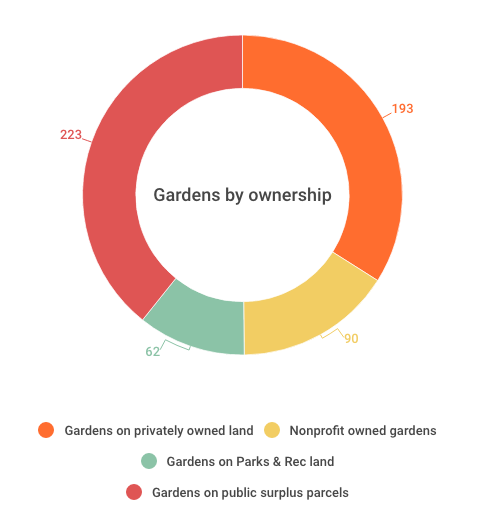

Meekings, like many others at the hearing, is worried about losing the rest of the Master’s Work Community Garden’s lands, which are also publicly owned. Out of the 568 parcels used for farming in the city, 285 are publicly owned, 193 are privately owned and 90 are owned by nonprofits, based on data from FPAC.

Development pressure is creating new challenges for gardeners across the city, and in many cases it’s City Council that controls the future use of these properties. Urban agriculture leaders called for clear pathways to stabilize land tenure, and a commitment to the deliberate, strategic protection and creation of gardens and farms.

Although Wednesday’s hearing lasted more than three hours, only a few people left City Council’s chambers. It was a rare occasion that gathered most of the city’s actors involved in urban farming in one room, and everyone was enthusiastic.

The council members’ hearing table was decorated with African eggplants and Thai Roselle grown by refugees in South Philly. The whole Committee attended at times, with councilmembers Cindy Bass, Jannie Blackwell, Helen Gym, Derek Green and Cherelle Parker filtering in and out.

Councilwoman Blondell Reynolds Brown, chair of the Committee on the Environment, marveled at the diversity of the crowd and congratulated Councilman Al Taubenberger for calling for the hearing.

“I have struggled as I sit here, trying to figure out and remember, the last time we had an audience of witnesses, testifiers and advocates that were as richly diverse -in terms of age, in term of cross sections of the city, in terms of ethnicity, in terms of energy and enthusiasm. This is remarkable, absolutely remarkable,” Reynolds Brown said as the hearing concluded.

Councilman Taubenberger, a Republican with a degree in Agronomy, said that diversity reflected “the power of this type of agriculture.”

Representatives from Philadelphia Parks and Recreation, the Office of Sustainability and the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture all expressed their commitment to support the city’s efforts on urban agriculture.

“As Mayor Kenney seeks to build equity and investment across neighborhoods, urban agriculture requires minimal public investment, with high yields in community impact and benefits,” said Kathryn Ott Lovell, commissioner of Philadelphia Parks and Recreation. “We have the opportunity to create innovative urban agriculture projects that can feed communities, create jobs, empower our citizens, educate our youth and improve our urban ecosystem.”

Scott Sheely from the Department of Agriculture said his agency wants to share the city’s experience in other cities in Pennsylvania and to contribute in different initiatives. “We have to figure out how to do that, but we are here, we are ready and we’re eager to make that happen,” he said.

Councilman Green asked Sheely if the Department of Agriculture has been in conversations with the Department of Health regarding rules for growing medical marijuana. Sheely said there have been conversations, but they haven’t get to the point of discussing rules and obligations. He expected that to happen in the next 3 to 6 months.

Several groups who represent coalitions of gardeners and urban farmers, including the FPAC, the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS), and Soil Generation, painted a picture of urban agriculture as a vulnerable asset and offered recommendations to facilitate a more strategic approach.

“Hundreds of these spaces emerged as neighbors transformed abandoned and disinvested places into vibrant community assets,” said Cahn, FPAC co-chair. “And hundreds of these spaces are still at risk of being lost. This simultaneous push-pull of possibility and precariousness reflects the overall picture of urban agriculture today in Philadelphia.”

For that reason these advocates asked Council to create an office to coordinate the city’s ongoing urban agriculture work, to appoint an urban agriculture advocate to the Philadelphia Land Bank, to contribute capital, and explore incentives.

The FPAC and PHS asked City Council to commit to 1 to 5 new acres for growing food in every district in the city.

“Land preservation is crucial to support the long-term investment PHS and growers make,” said Matt Rader, president of the PHS, home of the City Harvest program that grows and distributes 250,000 seedlings to more than 100 growing sites and trains gardeners and teachers.

Kirtrina Baxter, from Soil Generation Coalition, a black-led gardening coalition with members all over the city, said Soil Generation want to prioritize existing community gardens, have longer leases, and have transparent pathways to ownership. And because the Land Bank has the potential to do that, they want to work within it.

Others spoke to the economic benefits of urban farming. “Today we employ over 40 people and generate more than 2 million dollars in economic activity each year on a block in Kensington that was written off and abandoned for decades,” said Ryan Kuck from Greensgrow Farms.

“Nothing brings people together like food,” said Juliane Ramic, from the Nationalities Service Center and Growing Home Gardens where Southeast Asian refugees work together with African immigrants and local Philadelphians.

Petry Carrasquillo, from Campesinos of Norris Square, a group of neighbors that support Las Parcelas gardens in El Barrio in North Philadelphia, said people from “Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Colombia, Palestine, Virginia, Kentucky, New Hampshire, New Jersey and Philadelphia” worked together in their plots.

Because the city doesn’t provide water and electricity to vacant land, the gardeners have to learn how to use rainwater, solar power, allowing them to “practice a sustainable lifestyle,” said Carrasquillo, and to provide their families with healthy and affordable healthy food in neighborhoods that are often food deserts.

“I cannot convince high quality grocery store chain to open stores in Southwest, nor can I lure the education or jobs we would need to keep strong business in our community, but I can grow a seed,” testified Chris Bolden Newsome, from the Bartram’s Farm and Community Resource Center. “We need to have access to vacant land in Philadelphia not just to grow food but to build safer more involved neighborhoods.”

Paul Mendoza, a northeast Philadelphia resident and one of several students from the W.B. Saul High School of Agriculture Science in Roxborough in attendance, said farming has the potential of “taking kids off the street and having them work in a garden that they will be proud of.” Why waiting for kids to grow up and improve this world, he asked the councilmembers, when “we can fix things today.”

Councilman Taubenberger said Council would evaluate if there were any need for legislation. In regards with the list of recommendations offered, he agreed that having an agriculture advocate on the Land Bank would be helpful. He wasn’t so sure about committing to create 1 to 5 new agricultural acres in every district.

“Good agriculture land is also good building land, because it’s firm, it’s sturdy, it’s well drained, so that type of land is in a premium in the City of Philadelphia and that might be a little bit of a push,” he told PlanPhilly. “But expanding the gardens even if it’s by several hundred thousand feet? That’s a good thing. Whether we get to the 1 to 5 acres, I’m not sure. But we can try.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.