A Penn physicist accidentally created X-rays over 130 years ago. His family is now donating some of the earliest known images

Images taken in 1896 by Arthur Goodspeed of coins inside a small purse were a precursor to medical X-rays and the birth of radiology in the U.S.

Listen 1:49

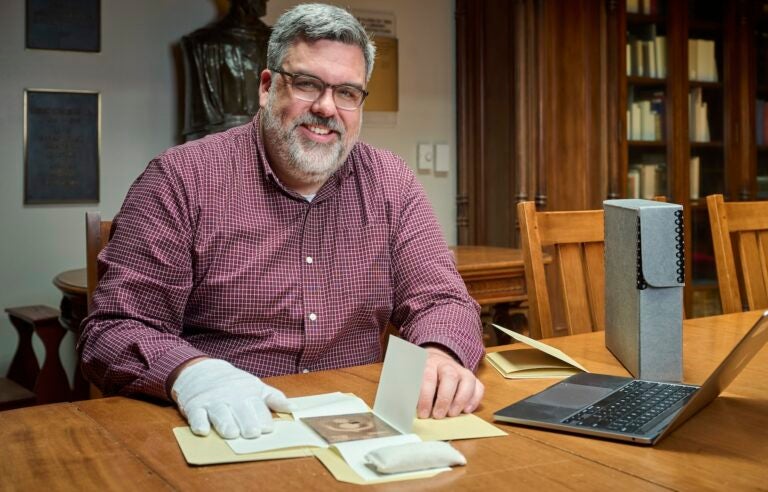

University of Pennsylvania archivist John Bence handles a glass plate showing one of the earliest known x-ray images taken by Penn physicist Arthur Goodspeed in 1896. (Courtesy of Penn Medicine)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

The box was small and looked worn, with a faded logo from the Wanamaker department store on the lid. Descendants of University of Pennsylvania physicist Arthur Goodspeed stumbled upon it among various family heirlooms and artifacts.

Inside were two old, thin glass plates, with black and white images printed on them. They were a bit fuzzy, but showed the upside-down U-shape of metal in the frame of a coin purse and two dark circles at the center, perhaps silver dollars or quarters.

The glass plates, authenticated by archivists and conservationists at Penn, were taken in Philadelphia by Goodspeed in 1896. They are believed to be among the earliest X-ray images in the world, an immediate precursor to medical X-rays of human bones and body parts and the birth of academic radiology departments in the United States.

Goodspeed’s family has now donated the plates back to the university and its archives, which were recently on display for staff.

While Goodspeed quickly realized the potential for this new technology, Dr. Pari Pandharipande, chair of the Perelman School of Medicine’s Department of Radiology, said it’s unlikely he could have known this would lead to a whole field of practice and other types of medical imaging like ultrasounds, MRIs, CT scans and more.

“The field has become incredibly important in medicine, but also in other areas,” she said. “One of the things that’s interesting to think about is, what is the X-ray of today? That is a really exciting thing to think about, it’s also a really intimidating thing to think about at the same time.”

How an accident led to a scientific discovery

In a lecture room at the University of Pennsylvania in 1890, Goodspeed and photographer William Jennings were experimenting and trying to create images of coins and brass weights using electrical charges.

When the two men were done, they put their work to the side, stacking several photographic plates atop each other and leaving a couple stray coins laying on the top.

Goodspeed then showed Jennings a collection of Crookes tubes, which are glass vacuum-like cylinders used to demonstrate how cathode rays, or electron beams, behave. When high voltage is applied and the beams bounce off the glass, they emit a florescent, glowing discharge.

While they were figuring out how to photograph the glow, the Crookes tube was giving off radiation, which traveled through space and other objects to reach the nearby stack of photographic plates and the discarded coins.

When the plates were later developed, Goodspeed and Jennings couldn’t explain the faint small circular marks, or shadows, that appeared on the images. They didn’t spend too much time fretting over it, but Goodspeed kept the images, said University Archivist John Bence.

“He knew something happened and ‘I might want to look at this someday’ sort of thing,” Bence said.

Meanwhile, German scientist Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was exploring this process with more intentionality in a laboratory nearly 4,000 miles away.

Using dark rooms, Crookes tubes and electric currents, Röntgen discovered a way to capture images of rays that could pass through objects and materials of one kind, and reveal objects of another underneath.

He used this method to take an image of his wife’s hand, which showed dark shadows of her finger bones and a ring she was wearing surrounded by a more transparent or translucent outline of her flesh.

Röntgen, who is credited with discovering X-rays and would go on to win the Nobel Prize, published his findings in the winter of 1895. Goodspeed in Philadelphia, having read about the new science, realized what he and Jennings had accidentally done several years before.

“Like, ‘Oh, that sounds familiar. I was fooling around with Crookes tubes and photographic plates and created a shadow-like image,’” Bence said.

That’s when archivists believe Goodspeed replicated his original accident by taking new images of a coin purse in 1896. He then quickly partnered with Penn surgeon Charles Lester Leonard to apply X-rays to people.

Some of Goodspeed’s earliest patient X-ray images, which were called skigraphs or roentgenograms at the time, were taken of heads showing teeth, jaw and skull bones. Those images are part of the Yale Peabody Museum in New Haven, Connecticut.

Improving X-rays and the future of radiology

It still took some time for the outside world to catch up with the science, and it wasn’t completely understood at first. Bence said that was pretty clear by a 1903 article in the New York Times.

“It says like, a scientist in Philadelphia discovered invisible rays that emanate from the human body and they were calling it the ‘human ray,’” he said, laughing. “Scientific communication is so much more immediate now, but it took a while to translate and move around and get around.”

It was pioneering work, though, said Penn radiologist Dr. Mitchell Schnall. Before X-rays, there was a lot of guesswork in figuring out what was going on inside the body, and where, that could be causing pain or illness.

“Even for foreign objects, penetrating objects, they didn’t know where they were. They couldn’t see broken bones,” he said. “Things also we take for granted — kidney stones, bladder stones.”

Goodspeed also later found ways to improve X-ray imaging by creating a screening mechanism in order to make the radiation safer for patients and doctors.

“It decreased the doses needed to make X-rays by about an order of magnitude by about a factor of 10,” Schnall said.

Schnall always knew the story behind Goodspeed and his contributions to the field of radiology, but said it’s been exciting to see early, physical evidence of those discoveries in the glass plate images.

So much of medicine can be about looking at the challenges facing health providers in the present, Pandharipande said. Moments like this, she said, can be a reminder that many medical innovations can begin in the most unsuspecting places.

“I think that’s the incredible thing about medicine,” she said. “When you think about leaps and bounds in medicine, often it is based on something that you can’t even imagine today, and so part of what we have to do is keep our eyes and ears open for that.”

The plates will be kept in Penn’s archives and temporarily displayed on specific occasions as they cannot be exposed to light for long periods of time.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.