UPenn library acquires the papers of Ashley Bryan, a pioneering African American poet and artist known for children’s books

The children’s book artist is a pioneer in African American literature.

Listen 1:40

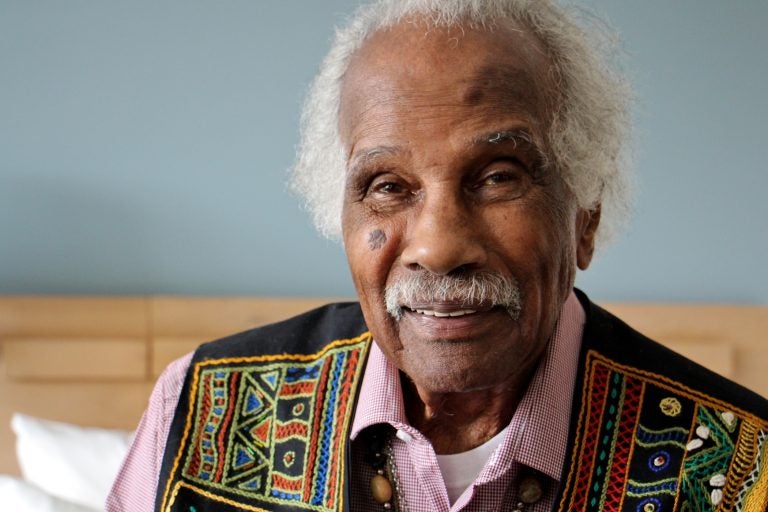

Children's book author and illustrator Ashley Bryan, 96, has donated his papers to the University of Pennsylvania. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

A few years ago, as Ashley Bryan was approaching 90 years old in his home on Little Cranberry Island off the coast of Maine, he started to think about preserving his legacy.

Or, rather, not preserving it.

“At one point, Ashley said that when he died people can just come and take what they want,” said Nick Clark, founding director of the Ashley Bryan Center in Maine.

“Fortunately, there were a lot of people on the island and family members who did not think that was a good idea,” he said. “They didn’t give Ashley the immediate dope-slap. They let it simmer for a while to let it come around to his way of thinking.”

Bryan has been making children’s books for almost 60 years. In 1962, he was the first African American to publish a children’s book as an author and illustrator. He was also a pioneer in creating stories centered on children about African and African American history and culture.

He came to publishing relatively late in life. He had a teaching career that spanned ten different colleges, including the Philadelphia College of Art (now University of the Arts) and Lafayette College in Easton, Pa.

He was 40 years old when he published his first children’s book.

“It was impossible. I couldn’t get into the field for years and years,” said Bryan.

His first book was a retelling of African folk tales.

“They were told in a very academic way, and I wanted to open up the spirit of the voice,” he said. “I worked with the language and poetry to open up the spirit of the story being told.”

Since then Bryan has worked on about 50 books, including illustrating books by poet Nikki Giovanni and novelist Richard Wright. He has won the Newbery Honor, the Coretta Scott King award, and the Hans Christian Andersen award.

He also served in World War II, in a segregated company at the invasion of Normandy. He went on to study art in New York and Paris, where he befriended poet Robert Creeley and followed cellist Pablo Casals.

“In 1956, he gets a Fulbright Scholarship and goes to Freiberg, Germany, because he wants to learn German so he can read [poet Rainer Maria] Rilke in the original,” said Clark. “This is the kind of mind at play.”

Bryan’s passionate life and wide-ranging interests are collected in his papers. When it came time for the Ashley Bryan Center to find an appropriate repository for the archive, they looked near and far.

“With his long residency in the state of Maine, it was hopeful the archive would stay there,” said Clark. “But when you start looking at what it consists of, it begged for a major research institution.”

Clark was introduced to the University of Pennsylvania libraries by the widow of another children’s book author, William Steig, whose papers are held there.

Penn Library Senior Curator Lynne Farrington leapt at the chance to acquire the Bryan papers because Bryan life represents more than children’s books.

“He sees art as his salvation, as a way to deal with what’s happening in this country,” said Farrington. “He found in Maine, on a little island, a community that embraced him in a way that other parts of this country were unwilling to do.”

Farrington is not getting everything. Bryan is still living and working mostly on Little Cranberry Island (splitting his time with family in Houston, Texas) and is keeping a portion of his archive with him. On the event of his passing, much of his archive will likely stay in Maine, where he has set down deep roots.

Farrington was not able to say just how much material has arrived at Penn, just that it’s “over 50 large containers.” The formidable job of sorting, cataloging, and indexing the archive is in front of her. She expects the collection to be an important research component appealing to a wide range of fields.

“Children’s literature has become more and more important in the academic world as more people realize that children’s literature has such an influence on people, beyond their childhood,” said Farrington.

Be that as it may, Bryan still prefers the company of children than that of academics.

“I’ve always worked with little ones, with children,” he said. “I love the way they think and the way they work out what the world means.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.