U.S. goal to be ‘first’ on devices worries former regulators

Dr. Jeffrey Shuren was adamant: The United States would never cut corners to fast-track the approval of medical devices.

In this June 22, 2016 photo made available by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Dr. Jeffrey Shuren, the FDA's Director of the Center for Devices and Radiological Health, speaks at FDA's Celebration of the 40th Anniversary of the Medical Device Amendments. Under Shuren, new device approvals have more than tripled, while warnings to device manufacturers about product safety and quality have fallen roughly 80 percent, an Associated Press investigation found. (Michael J. Ermarth/FDA via AP)

Dr. Jeffrey Shuren was adamant: The United States would never cut corners to fast-track the approval of medical devices.

“We don’t use our people as guinea pigs in the U.S.,” Shuren said, holding firm as the new director of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s medical devices division.

Again and again in 2011 — four times in all — Shuren was summoned before Congress. Lawmakers accused the agency of being too slow and too demanding in reviewing new devices like heart valves and spinal implants, driving U.S. manufacturers overseas where products faced less rigorous review. Each time, he pushed back.

And yet the next year, Shuren and his team adopted an approach that surprised even some of his closest colleagues: The FDA would strive to be “first in the world” to approve devices it considered important to public health.

The agency’s shift mirrored the talking points of the $400 billion medical device industry — a lobbying behemoth on Capitol Hill — and ushered in a series of changes that critics say have allowed manufacturers to seek regulatory approval for high-risk devices using smaller, shorter, less rigorous studies that provide less certainty of safety and effectiveness.

Under Shuren, annual new device approvals have more than tripled, while warnings letters to device manufacturers about product safety and quality issues have fallen roughly 80 percent, an Associated Press investigation found.

The assortment of medical devices now on the market includes spinal rods that can leave metal shards in children and a nerve-zapping obesity implant that may not work for many patients.

The cheaper and faster medical device approvals began despite multiple, high-profile safety problems involving pelvic mesh, hip replacements and other implants.

An AP analysis of FDA data shows that since 2012, tens of thousands of injury and death reports have been filed in connection with devices that were cleared through a streamlined pathway that minimizes clinical trial testing. The FDA’s database for reporting device problems often includes incomplete, unverified information submitted by manufacturers, physicians, lawyers and patients. Because of these limitations, it’s often unclear whether a device played any role in an injury or death.

In response to questions from the AP, the FDA said its “first in the world” goal was not about a competition with other countries but rather was adopted as part of a strategy that also focused on quickly identifying defective products to ensure U.S. devices “remain safe, effective and of high quality.”

The agency said it has focused on taking steps to reduce the time and cost of device development “that do not compromise our standard of reasonable assurance of safety and effectiveness.”

Warning letters have declined, the FDA said, because the agency is using a new approach that involves fewer warnings but more inspections to oversee companies that violate its rules.

Last week, the FDA announced a new goal to be “consistently first” among the world’s regulatory agencies to identify and address medical device safety issues.

The agency also rejected the idea that Shuren’s approach to regulation has changed over time, saying he has worked for years to improve patient safety.

Still, some current and former FDA officials are worried about the ambition to be first on approvals. They include Dr. Peter Lurie, who calls the agency’s new direction “an invitation to a race to the bottom for scientific standards” seemingly prompted by industry pressure. Lurie held senior posts at FDA from 2009 to 2017 and now heads the nonprofit Center for Science in the Public Interest.

The FDA’s medical device standards are still considered among the highest in the world, requiring “reasonable assurance” of both safety and effectiveness. But by trying to outpace countries with less stringent requirements, Lurie said, the FDA has opened the door to lowering its own standards to achieve its goal.

The FDA’s struggle to find the right mix of regulation and innovation in overseeing more than 190,000 medical devices — from pacemakers to contact lenses to surgical robots — has been chronicled for decades by government inspectors and outside researchers.

For almost as long, the agency has had a symbiotic relationship with industry.

Fees paid by medical device manufacturers for the review of their products now cover about 35 percent of the annual budget of the agency’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health. The last four officials in Shuren’s position have gone on to higher-paid positions in industry.

In addition, Shuren’s wife, Allison, is a former lobbyist who now leads her law firm’s health-care practice group and advises medical device clients, among others, on regulatory and legislative issues. The FDA said Shuren passed a “rigorous ethics review process” before assuming his position that addressed potential conflicts of interest. He also recuses himself from FDA matters involving clients represented by his wife or her firm, the agency said.

Joshua Sharfstein, a former FDA deputy commissioner now teaching at Johns Hopkins University, praised Shuren for balancing the competing demands of protecting the public while promptly approving beneficial new devices.

“I don’t think there’s a viable way to be the head of devices and be in open warfare with industry all the time,” he said.

But some who spent years working under Shuren say speeding up product reviews became the clear priority after 2012.

“Basically, it was ‘We need to find ways to get products on the market quicker, faster and we need to figure out how to reduce the premarket data requirements,'” said Christy Foreman, an industry consultant who spent 22 years at the FDA, including four years leading its device review office.

The FDA notes that laws passed by Congress require the agency to emphasize the “least burdensome approach” to reviewing new devices. But the agency itself helped fashion those laws, working with industry lobbyists and lawmakers on provisions that effectively limit its ability to request additional evidence from manufacturers.

The philosophy of “acceptable uncertainty” is sometimes the price of making life-saving devices quickly available, according to the FDA. At the same time, it acknowledges its main system for tracking problems is riddled with “incomplete, inaccurate, untimely, unverified or biased data.”

“So instead, you have devices of unknown benefit on the market that still harm patients,” said Dr. Rita Redberg, a prominent medical researcher and cardiologist at the University of California San Francisco. “I do feel that the FDA sees their role as making industry happy and not as much protecting the public health.”

Every day, patients in the U.S. and around the world benefit from medical technology. The inventions of this global industry include implants that help the deaf hear, implantable lenses that restore sight to the elderly and cardiac pumps that keep failing hearts beating.

For most of the last century, medical devices were not regulated in the U.S. But a series of high-profile safety problems in the 1970s — including deaths, miscarriages and injuries caused by a contraceptive implant — pushed Congress to intervene.

The laws that resulted are both more complex and less demanding than those governing drugs.

To win FDA approval, for example, most new prescription drugs undergo two large, rigorous clinical studies proving they benefit patients. But most new medical devices enter the market with no clinical trial testing.

Historically, more than 95 percent of FDA-reviewed devices on the market went through a streamlined process in which they need only show that they are “substantially equivalent” to a product already on the market. Typically, only devices considered high-risk, like heart pumps, must demonstrate safety and effectiveness in humans, but even those can sometimes rely on existing scientific data as opposed to new studies.

On Monday, the FDA proposed changes to the streamlined system that would push manufacturers to incorporate more up-to-date technology into their devices. But some of the major reforms could take years to implement.

Some experts have long argued that this fast-track pathway was never intended to be permanent. As framed by Congress in 1976, the system was originally meant to be a temporary way to grandfather in thousands of devices already on the market that weren’t considered high-enough risk to require immediate review. But instead of being phased out, it became mainstream.

The industry contends that flexibility is critical to innovation, allowing manufacturers to quickly and cheaply experiment and improve. An FDA review under that process costs about $11,000, compared to $320,000, under the more rigorous standard.

The result, though, is that some medical products barely resemble the decades-old “predicates” they reference in applying for FDA clearance. And even when old devices have been linked to injuries or death, future products are allowed to reference them for approval because the FDA lacks explicit legal authority to swiftly intervene.

In more than four decades, the FDA has banned only two products — powdered surgical gloves, which caused allergic reactions in patients, and fake hair implants, which caused infections and didn’t work. The agency says its ability to ban products is “bound by federal law” and is essentially limited to devices that are either deceptively marketed or unreasonably dangerous.

The U.S. device system is “basically set up to get things on the market, not to get things off the market,” said Larry Kessler, a University of Washington professor and consultant who worked more than a decade in the FDA’s device center.

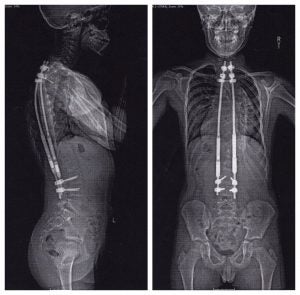

A device used to treat childhood scoliosis illustrates how quickly manufacturers can win FDA approval with minimal clinical trial testing.

The MAGEC rod uses remote-controlled magnets to gradually extend titanium columns implanted in children’s backs to correct debilitating spinal curvature. It is marketed as an alternative to traditional implants, which require frequent surgeries to manually extend the rods as a child grows.

Prior to clearing it for use in the United States, the FDA allowed the MAGEC rod’s California-based manufacturer, Ellipse, to begin exporting its product overseas.

The company enlisted a Hong Kong surgeon to conduct its first human trials after winning European approval in 2009 following experiments in pigs. In a company-funded study published three years later — based on the results of just two patients — the surgeon concluded the MAGEC rod “improves quality of life and is more cost-effective.” The rods were later implanted in patients in Australia, Israel, Korea and elsewhere.

The company had assumed it would need to conduct a large clinical study including American children to win FDA approval for use in the United States, Dr. Behrooz Akbarnia, a San Diego-based surgeon and company consultant, said in an interview.

But in early 2014, the FDA informed the company it could seek approval via the streamlined process, Akbarnia said. Ellipse claimed its device was “substantially equivalent” to a mechanical implant developed in the 1950s. It was cleared for use in the U.S. by the FDA in just 35 days.

“That was one of the things that surprised me,” Akbarnia said, “because it was so fast.”

The approval also “shocked the spine industry,” according to an article by Ellipse’s former vice president of engineering Tiger Buford, who did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

More than 2,000 children have been implanted with MAGEC rods worldwide, according to company filings by Ellipse, which was purchased by Nuvasive in 2016 for roughly $400 million.

Anthony Wainess was 9 when he became the first U.S. child to have MAGEC rods implanted in 2013 under a “compassionate use” exemption by the FDA. The rods temporarily helped the boy’s spine grow correctly, but began breaking within a year and were removed in 2016.

Anthony’s doctors theorized his body might be having an allergic reaction to the metal rods, according to his father, Steven Wainess.

The FDA told the AP that the MAGEC rod was cleared based on laboratory testing, animal studies and a clinical study “to demonstrate the device is safe and effective.”

The agency said it requires makers of all spinal implants to include warnings about potential risks, noting that the MAGEC rod’s labeling warns that it can break, move, corrode, cause pain and should not be used by patients with metal allergies.

Researchers in Europe have identified cases of metallosis in children with the rods, the tissue around their spines stained black by titanium shards and debris.

The long-term effects of titanium metallosis are not yet known, but metal debris in patients with chrome and cobalt hip implants can cause bone and tissue damage. The all-metal hip implants, also cleared through the FDA’s streamlined path to market, were implanted in an estimated 500,000 Americans before the FDA reclassified them as high-risk in 2016. Today, they have largely been recalled or phased out.

In a paper published in January in the medical journal, Spine, British orthopedic engineer Thomas Joyce said all 34 MAGEC rods examined by his lab at Newcastle University showed signs of metal wear, which could lead to debris spreading throughout children’s bodies.

The level of metal debris from MAGEC rods is about 100 times the levels he’d previously seen with hip implants, “a shocking amount,” he reported. Joyce has worked as an expert witness for lawyers suing metal hip makers. He donates his payment to his employer, per university rules.

Nuvasive said in a statement that its device has been shown to be effective in helping avoid the “pain, elevated complication rates, and psychological distress” of traditional spinal rods.

“While no technology in these patients is without risk, we have also seen MAGEC rebuild patient and family lives,” the company said.

Joyce said Nuvasive initially cooperated with his research, providing materials to help with his tests. But after his research was published, he said the company sent a letter to spine doctors worldwide questioning its validity.

Joyce said he’s simply trying to answer basic safety questions that haven’t been addressed by the company or regulators: Why does the MAGEC rod cause metallosis, and what are the long-term effects on children?

A device that claims to treat depression by beaming rapid-fire bursts of magnetic energy into the brain’s prefrontal cortex had a similarly smooth path to market, even though its benefits were unclear.

Between 2012 and 2016, former U.S. military members participated in a Department of Veterans Affairs study of the transcranial magnetic stimulation device, or TMS. As of 2018, the VA has spent more than $3.4 million acquiring dozens of the machines and related supplies, based on the FDA’s approval.

The FDA cleared TMS technology for the U.S. market in 2008 even though the agency’s own advisers said data submitted by the original manufacturer failed to establish its effectiveness. In fact, the advisers called its effect “marginal,” ”borderline” and “questionable.”

The experts did note that TMS therapy appeared “reasonably safe,” producing only minor complications such as headaches and scalp pain. That compared favorably to older devices used for hard-to-treat depression, including electro-shock therapy.

The FDA eventually approved the device through a pathway reserved for “low to moderate” risk devices that are not equivalent to previously approved devices.

Under Shuren’s tenure, six more TMS manufacturers have come on the market, mainly by piggy-backing off the original FDA clearance.

This June, when the VA published the findings of its study, they echoed the results of a decade earlier: TMS made almost no difference in patients’ depression. The authors offered several explanations, including that veterans often have multiple psychiatric problems that complicate treatment.

The American Psychiatric Association’s guidelines describe TMS as offering “relatively small to moderate benefits.” And even when TMS treatment is successful, its long-term durability has not been established in rigorous patient studies.

Still, with persistent marketing from manufacturers, TMS has gradually won acceptance as an alternative to antidepressants. Some clinics also advertise unapproved uses of the device, including for autism, Alzheimer’s and post-traumatic stress disorder.

More than 800 U.S. clinics have the devices, according to a filing from the original TMS manufacturer, Neuronetics Inc. The firm tells doctors they can recoup the cost of a machine by treating just 12 patients, with a typical course of treatment costing up to $10,000 for 30 or more sessions over four to six weeks.

“The clinics are proliferating, the insurance is reimbursing, but we still don’t exactly know what kind of patients should be receiving this intervention,” said Dr. Dost Ongur, a Harvard Medical School psychiatrist and editor of the journal that published the VA study.

TMS can be effective for certain patients, Ongur and other psychiatrists say, but identifying them can be challenging.

The FDA said it approved TMS after determining that its benefits outweighed its risks. The device’s approval is limited to patients who have failed to respond to drug therapy with at least one antidepressant, the agency noted.

Neuronetics said in a statement that its device has been proven effective in studies of more than 900 patients and is covered by more than 65 private insurers and the government’s Medicare plan. And Magventure, which makes the device used in the VA study, said TMS’ impact on the brain is “a well-established fact,” though researchers are still exploring the “optimal way” to treat different patient types.

But skeptics remain. The Blue Cross Blue Shield network’s unit for reviewing medical devices has assessed TMS three times, most recently concluding in 2014 that the studies “do not provide convincing evidence.” The group is considered a pioneer in evaluating medical technology.

Foreman, the former FDA review chief, said the “least burdensome” requirements that bind FDA reviewers make it difficult to demand better evidence for devices like TMS. In such cases, the agency’s position is generally “the device isn’t going to hurt anybody so let’s put it out there and let the consumer use it,” she said.

But even ineffective treatments for depression can be harmful, according to Diana Zuckerman, a depression researcher and president of the nonprofit National Center for Health Research, which assesses the quality of outside research and conducts its own.

“If you are going five days a week for a month, spending all this money and you feel you’re no better than when you started, you could end up more depressed,” Zuckerman says.

A new analysis of the TMS literature by Zuckerman’s group concludes that the treatment “is not shown to be beneficial compared to typical placebo effects.”

One of the rationales FDA cites for accepting uncertainty in new device safety and effectiveness is “patient preference,” which holds that the agency should consider patient opinions in its approval decisions.

Former FDA regulators say Shuren has repurposed that idea to justify putting even more devices on the market.

“Jeff tells wonderful stories in terms of ‘We’re doing this to make sure patients have this greatly improved technology,'” Foreman said. “But there’s another side to it, too.”

In recent years, patient preference information has been used to push approvals through the FDA’s pathway for high-risk devices, even in a case where the manufacturer failed to meet its own study goal.

In early 2015, the FDA approved a first-of-a-kind obesity device — an implantable stimulator that shoots electricity through the nerves connecting the stomach and brain. But less than a year earlier, the Maestro Rechargeable System had received a mixed review from the agency’s scientists and outside advisers.

To demonstrate effectiveness, the FDA and the manufacturer agreed Maestro patients would need to lose at least 10 percent more excess body weight than patients who received a sham treatment. But one-year data showed patients with the device lost only 8.5 percent more of their weight.

FDA scientists cautioned that long-term complications from removing and adjusting the device were not known. And some agency advisers said the demographic of study participants was unacceptable, since 93 percent were white and U.S. obesity rates are highest in African-Americans and Hispanics.

Still, the agency approved the device, citing a survey that showed patients were willing to accept the risks.

The patient survey, for which the FDA paid $280,000, is being used by regulators to “define minimum clinical effectiveness to evaluate new weight-loss devices,” the agency said, adding, “The FDA recognized obesity as an area of unmet patient need.”

The device manufacturer, ReShape Lifesciences, did not respond to requests for comment.

Earlier this year, Shuren addressed a conference of medical device industry executives, each of whom paid about $1,000 to attend.

Armed with dozens of PowerPoint slides, he explained how the FDA was approving more new devices in less time and credited his “north star” — the FDA’s goal to be “first in the world” to approve new devices.

He highlighted the agency’s new focus on “customer service,” including removing “unnecessary burdens” for companies and streamlining clinical trials.

“We all know that premarket clinical trials can be very costly, very time-consuming and, in some respects, of limited value,” Shuren said.

He explained that the FDA was now using easier-to-produce data to approve a variety of devices, including artery-opening stents, spinal implants and diagnostic tests.

Meanwhile, warning letters to device makers over safety, marketing and other issues have fallen to their lowest level in over a decade. The FDA says it has offset warnings with increased inspections and that companies continue to fix their violations at the same rate.

The stepped-up approvals and modified enforcement have the endorsement of President Donald Trump and his appointee, FDA Commissioner Dr. Scott Gottlieb, who has highlighted “acceptable uncertainty” as a key concept to “modernize” device regulation.

In September, the FDA began codifying that concept in draft guidelines for manufacturers, which would ease pre-market testing standards for certain devices, in exchange for companies conducting larger follow-up studies, even though the FDA’s own data show that many studies are not completed until five or more years after approval.

The FDA said in a statement that all devices carry a level of uncertainty, even after extensive testing. It said its guidance focuses on “breakthrough” devices, where “it may be appropriate to accept a little more uncertainty,” while still meeting FDA standards.

Lurie and other former regulators worry that the FDA is laying the groundwork for a “sliding scale” of medical evidence that will leave patients even more uncertain about the safety and effectiveness of devices.

“This guidance is basically a ‘come hither’ to industry, inviting them to ask FDA for the lower standards of evidence,” he said.

Follow Matthew Perrone at @AP_FDAwriter

Associated Press writers Holbrook Mohr, Meghan Hoyer and Reese Dunklin contributed to this story.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.