Training the Navy SEALs of the teaching world

Listen

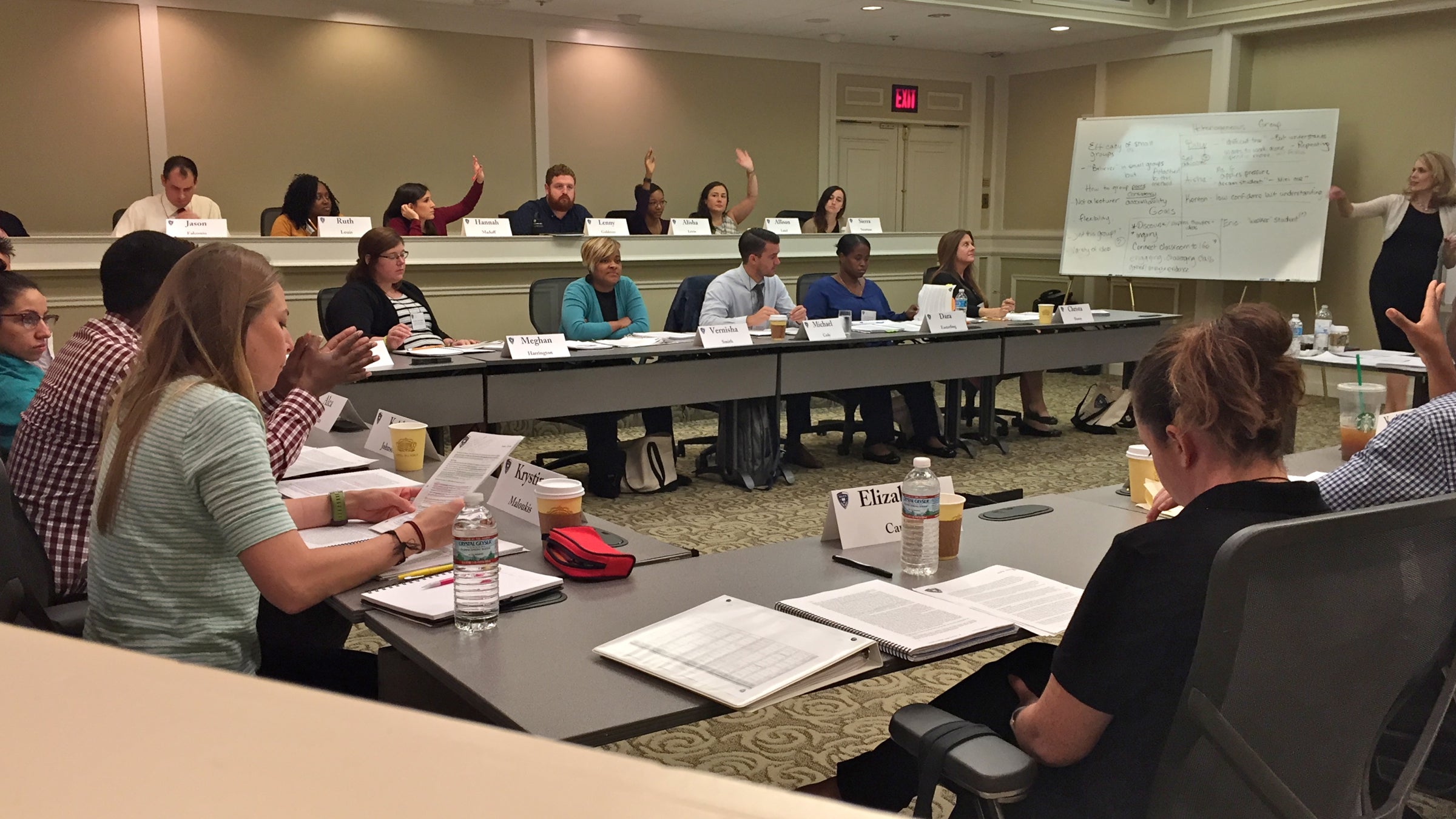

Top teachers gather for a seminar at the National Academy of Advanced Teacher Education or NAATE. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/WHYY)

Inside a conference room at a swanky hotel in Wilmington, Delaware, about 30 classroom teachers sit in tiered rows arranged like a mini-amphitheater. All eyes tilt toward the professor at the front of the room.

Today’s lesson revolves around a case study, much like the kind you’d find in a business school. But instead of sugar-cane exports or European currency, the topic of this case is “using diverse small groups effectively.”

The case is set in a fictional Brooklyn classroom and dives deep into the classroom behavior of four students — Billy, Aisha, Eric, and Kenton — who’ve been grouped together for an assignment on the Cold War. It is loaded with details on each student’s proclivities, their teacher’s personal history, and the exact nature of the assignment.

Over the next 90 minutes, the discussion barrels into territory few outside the teaching profession could comprehend. The teachers cite academic studies on classroom dynamics, tossing around terms such as “task-oriented assignment” and “ill-structured problem” the way scientists might talk about hemoglobin.

It’s the kind of conversation that makes a lay person realize something most teachers already know: Classrooms are complicated and teaching isn’t easy.

Opportunity for educational elite

That sentiment lies at the heart of the National Academy of Advanced Teacher Education, an organization aiming to provide advanced training for the nation’s best instructors. NAATE wants its graduates to be the Navy SEALs of the teaching world, plying them with specialized knowledge and professional validation in a field where training tends to be dull, standardized, and aimed at the lowest common denominator.

“Every other industry looks at its ‘A’ players,” says NAATE co-founder and chief program officer Deborah Levitzky. “They invest in them. They know who they are, and they wanna keep them. In this industry that’s a radical shift.”

NAATE’s primary course — known as its Teacher Leader Program — brings together top teachers from from around the country for 23 days of intense instruction spaced out over two years. It’s like the Ivy League for classroom teachers, right down to the spiffy NAATE crest that seems to emblazon just about everything.

It feels elite, and that’s exactly the way NAATE wants it.

Since 2009, NAATE has trained 540 teachers and 140 school leaders. The courses cost between $12,000 and $16,000 — even with outside philanthropists subsidizing some of the tuition. Schools and districts pick standout teachers to send, then pick up the tab.

The Philadelphia School Partnership — one of the area’s largest education funders and a prominent advocate for educational reforms — recently plunked down nearly $450,000 to send 20 Philadelphia teachers and eight city administrators to NAATE. They came from four schools — two charters, one Catholic school, and one district school. Eventually, 15 percent of the teaching staff at James G. Blaine Academics Plus, Freire Charter High School, First Philadelphia Preparatory Charter School, and St. Malachy School will have passed through one of NAATE’s programs.

On the national level, NAATE has received support from major reform proponents such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the Walton Family Foundation.

‘How do you get even better?’

NAATE’s calling card is its intensity. Participating teachers receive reams of literature to review and get daily feedback on their performance. Even visitors may receive a thick packet of prep materials in the mail before their arrival.

It is a far cry from the staid PowerPoint presentations many associate with school-based professional development. That’s largely because it’s designed for veteran teachers who want to get better at their craft. Too often, says Levitzky, professional development programs in schools districts focus on beginning teachers or others who are struggling just to reach adequacy.

“If you’re a brand-new teacher, you need to learn the rituals and the routines and probably some foundational skills as a teacher,” she says. “Once you’re eight years in or 10 years in, the question is how do you up your game and how do you get even better?”

NAATE wants to be the destination for good, experienced teachers who crave more, teachers like Sister Regina Dougherty of St. Malachy’s Catholic school in North Philadelphia.

Dougherty, a veteran music teacher, says that by the time you’ve been in the classroom for a couple decades, professional development starts to feel repetitive.

“It’s another professional development,” she says. “Been there, done that, three, four times over.”

Not only is it boring, but routinized professional development sends a message that teaching doesn’t require constant refinement. Would you show a doctor a few slides on brain surgery and expect him or her to feel fulfilled?

“Everybody loves doctors. Everybody loves lawyers,” she says. “They’re willing to pay through the nose for the best. Well, we’re the best, too.”

Sean Burke, who teaches at a charter school in Newark, New Jersey, says she took her current job because it offered better professional development than is typically available. For teachers who care about their craft, opportunities to get better in a formal setting are hard to find.

“I care about my practice. I want teaching to be my long-term profession. And I do want to be better than the day before,” she says. “The only way I know I can get that is by going to top quality professional development.”

Matters of motivation, leadership and respect

NAATE’s goal is to both create better teachers through advanced training and fulfill the career ambitions of motivated teachers so that they stay in the classroom. Levitzky says 95 percent of the teachers in NAATE’s first five cohorts have remained in the profession.

NAATE did initially track a sampling of graduates to see if completing the program boosted student test scores. It did find a bump, but it was impossible to know whether those changes could be attributed to NAATE. Feeling uncomfortable with the scope of the data, the organization has shifted away from using test scores as a guage of the program’s quality. It does, however, point to surveys that show a vast majority of participants believe the training to be far better than what they typically receive.

“The program’s real impact is on mindset and softer leadership skills that don’t lend themselves to being measured by assessments,” says Juan Fernandez, NAATE’s senior director of school partnerships.

The organization thinks someday it can have a brick-and-mortar campus where thousands enroll every year. Those thousands will be loaded up not only with knowledge, but with the skills needed to pass that knowledge along to their colleagues. If it was successful enough, a place like NAATE could serve as a mark of excellence for its graduates and an aspiration for those still working their way up the ranks.

“We don’t confer the same level of respect on [teachers] as other professions,” says Levitzky. “NAATE treats every other teacher that comes through its doors like a consummate professional.”

Behind the maze of big words and reading packets, NAATE’s central crusade may be just that: professional development that treats its recipients like professionals.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.