Three genetic networks may play a role in autism, CHOP study finds

Autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder, is often hereditary. Dr. Hakon Hakonarson, director of the Center for Applied Genomics at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, says that’s helpful when it comes to developing treatment options.

“Our most recent finding is a meta-analysis that looks at genes that belong to the same family. So if one gene is deleted or missing, it can disrupt the whole pathway,” said Hakonarson.

His team genotyped 6,700 kids with autism and nearly 13,000 kids without any symptoms of autism, looking for clusters of mutations called copy number variations. CVNs are genes that are doubled or omitted in a sequence.

Autism causation is complex and variable, but Hakonarson says he has found three such genetic pathways that are particularly implicated in many kinds of autism. “This is the first time that this comes up as being significant sort of cascade or network of genes that constitute a potential for causality in autism,” said Hakonarson.

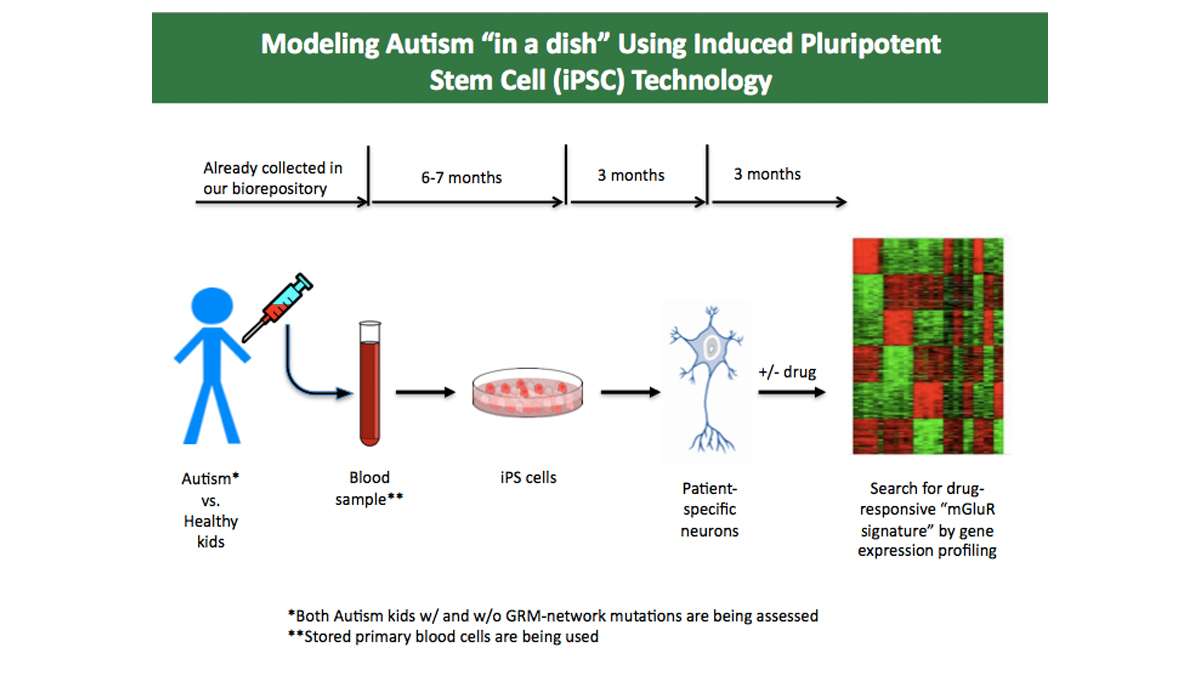

One of these pathways, called the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) signaling pathway, regulates basic functions such as neuron creation and connections in the brain, has been linked to autism in previous studies – and is also implicated in the development of ADHD and schizophrenia.

Hakonarson says this network is particularly promising for treatment – because there are drugs that act on that pathway already in the works. One drug in particular, which acts on the glutamate receptors, will be tested in the fall for its effectiveness in treating ADHD.

But, any treatment option needs buy-in.

Autism and cross-disability advocate Savanna Logdsdon-Breakstone says that research around behavioral health often fails to seek input – in research design, marketing and application of treatments — from the people it will impact.

“My biggest concern, whenever I hear that there’s gonna be new genetic research, is that a lot of times this research has not had a lot of autistic voices,” said Logsdon-Breakstone. “Genetic research in and of itself is not a bad thing, but we need to be very aware of how things end up being used, how they end up being funded. And when we base our marketing around fear and tragedy that that can have really disastrous consequences for real people.”

Logsdon-Breakstone says that any new treatment should focus on improving quality of life now – and not add to stigma against autism and other behavioral health issues.

“It’s really important to think about this in the context of things that will help us have better lives,” said Logsdon-Breakstone. “But we don’t necessarily want a cure. We want greater access to things, we want less anxiety, and we want things that will help us control our meltdowns.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.