The wounds of clergy sex abuse remain unhealed, but truth may yet see light of day

ListenArthur Baselice Jr.’s grief has pushed him into a self-imposed exile.

Almost 10 years after his son died from a drug overdose with links to his abuse by two Franciscan clergymen in Northeast Philadelphia, Baselice rarely leaves his house.

“I don’t want to go nowhere,” said Baselice.

Walking through the Baselice home in suburban South Jersey is like walking through a monument to their lost son, Arthur Baselice III. Pictures of him are everywhere. The urn with his ashes sits on a table at the entrance to the living room, where each night his father and mother light a candle in his honor.

Arthur’s bedroom, covered in sports memorabilia, is exactly the way he left it on the night that he died.

“Nothing’s changed,” said the father. “Same sheet, same bedspread. Everything is the same.”

Baselice Jr., 67, a retired Philadelphia detective who grew up a Catholic school kid in South Philadelphia, has a tattoo of his son’s face on his left forearm. Some of his son’s ashes rest in a bracelet on his right wrist.

All these years later, the pain hasn’t dulled. Baselice often wakes up in the middle of the night gasping for breath, tormented by what happened. Sometimes, as he jogs through his Gloucester County neighborhood – seemingly out of nowhere – he bursts into tears.

His wife, Elaine, and his daughter, Ashleigh, he says, are no better.

“Do I cry a lot?” said Baselice. “Yeah, most of the time.”

Baselice says he didn’t used to be an emotional person.

“Emotional?” he scoffs with the jaded laugh of a policeman. “Not at all. But this hit home.”

‘Makes me sick’

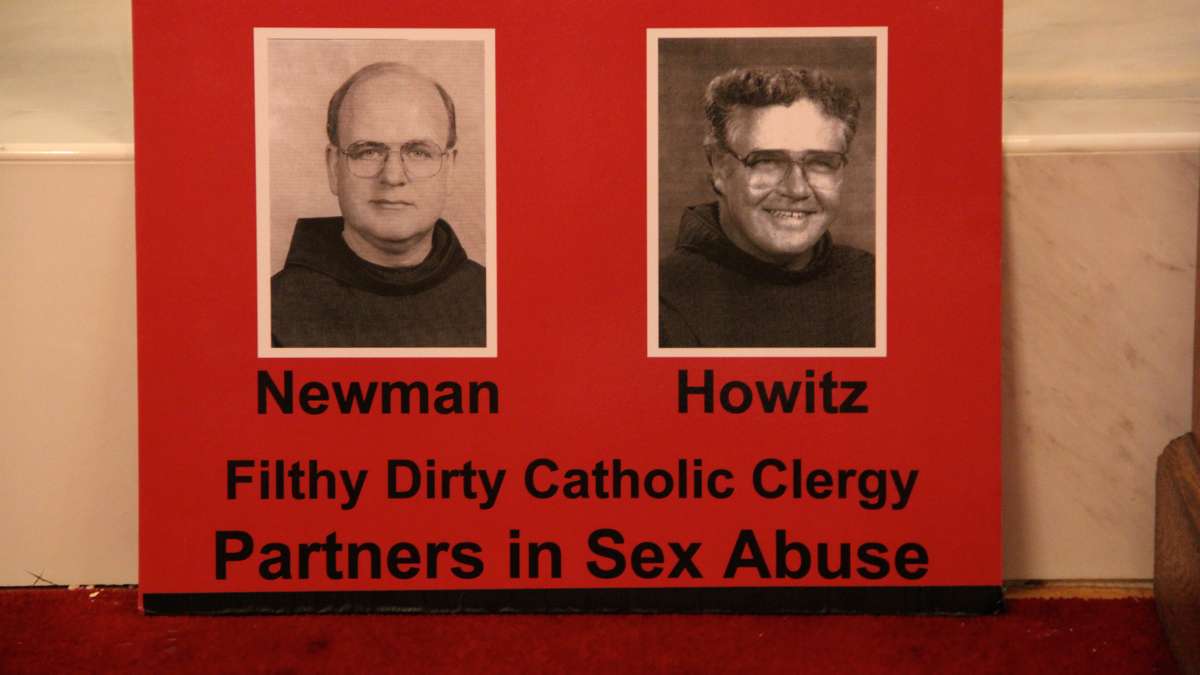

In 1994, Arthur Baselice III was a sophomore at Archbishop Ryan High School in Northeast Philadelphia. A gifted football player with a charming smile, Arthur started gaining the attention of the school’s principal, the Rev. Charles Newman.

The pair became close — at first innocently. But before long, a sexually abusive relationship developed.

During Arthur’s junior year, when the teen went to Newman for advice, the priest invited him into the Franciscan residence next to the school and gave him alcohol.

Before long, Newman was giving Arthur marijuana, cocaine and Oxycontin — numbing the boy to the sexual abuse he endured.

Later, Brother Regis Howitz, a maintenance worker at the school, abused Arthur as well.

In exchange for using Arthur to satisfy his perversions, Newman fixed the teen’s declining grades and exempted him from summer school.

As Arthur’s drug habit became an addiction, Newman fuelled the fire by siphoning money to him out of the school’s coffers — which continued well after Arthur graduated.

All the while, Baselice and his wife were in the dark. They had suspicions about Newman, but their longstanding trust in the church clouded their judgment.

“Newman came to my house and blessed my house when I moved to Jersey,” said Baselice. “Newman heard my confessions on a regular basis. I would would get Communion from Newman at the 6:30 Mass. All the while he was molesting my son.”

Baselice actually invited Newman and Howitz to his home for dinner once, which he can’t help recalling every time he walks through his dining room.

“Howitz sat here. Newman sat here. My son sat there. My wife sat there. And I sat there,” he said. “And that’s where they had dinner.”

Baselice didn’t find out the truth until about 2004, when Arthur — who was by then struggling with a heroin addiction — found the courage to give with his parents a letter he wrote in 2000, which he had been previously unable to bring himself to share:

“He is the one who started me drinking and gave me the money to buy drugs so he could have his way with me. It makes me sick to think about it,” the letter reads. “You always thought I liked Father Charles. The truth is I hate him! And I used him for what he did to me. […] I thought, at 17, I knew everything. The truth is I know nothing. […] He always told me that if I told anyone, he would kill himself.”

Newman eventually resigned from Archbishop Ryan when it was uncovered that he stole nearly $1 million from the school and his Franciscan order — a crime for which he served four years in prison.

But by the time the Baselice family attempted to file charges against Newman and Howitz for the sexual abuse, the statute of limitations had expired.

By 2006, after battling his heroin addiction for years — and plagued by memories of the abuse — Arthur died of an overdose in a Camden apartment.

He was 28, and he left behind a young son.

“I seen him the night that he went out. I said, ‘How you doing? You OK?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ That was it,” said Baselice, choking back tears.

The next morning, two detectives came to his house to tell Baselice the news about his son.

“There’s three types of death that they write up. It’s either natural, suspicious or homicide. And anything that’s suspicious or homicide has to go to the [medical examiner]. Have you ever been to the M.E.? Well I know what they do. And that’s what they did to my son,” said Baselice. “They cut his body open.”

Investigations by the Archdiocese of Philadelphia and the Franciscan order have since found Arthur’s claims against Newman and Howitz to be credible, and both clergymen have been moved to restricted, nonpublic ministry.

But they are supervised only by their religious superiors in the Order of Friars Minor of the Franciscans Assumption BVM Province.

“They don’t have a bracelet on,” said Baselice. “So these guys could wander around anywhere they want.”

Battle over statute of limitations

Changes to Pennsylvania law that were made too late for Arthur Baselice III now give victims born after 2002 until age 50 to file suits criminally and until age 30 to file civilly.

But Baselice Jr. and other victim advocates say those reforms do not go far enough.

They’ve pushed to completely remove any statute of limitations for childhood sexual abuse in Pennsylvania moving forward. They also want past victims to have a two-year window in order to file civil charges against their alleged abusers.

Sister Maureen Paul Turlish helped achieve those goals in Delaware in 2007. She’s on the board of the Greater Philadelphia chapter of Voice of the Faithful, a group of active Catholics who criticize the church hierarchy’s handling of clergy abuse.

“The sexual abuse of a child is soul murder and should have the same kinds of laws covering it as murder,” said Turlish. “There are no statutes of limitation on murder.”

State Rep. Mark Rozzi, D-Berks, has been the driving voice behind statute of limitations reform in Harrisburg.

Rozzi says he was raped by a priest in 1984 at age 13. He didn’t begin sharing his story until a friend and fellow abuse victim committed suicide in 2009.

Rozzi’s first effort at statute of limitations reform was criticized by state Catholic Church leaders because public employees, such as teachers, were exempted.

His latest bill on the issue removed those exemptions so that all who were sexually abused as children would have the same opportunity to file complaints.

Still, Rozzi says the church has remained a staunch, decisive opponent.

“They keep changing the line. They don’t want any move on reform,” said Rozzi in a telephone interview. “Their response is the statutes in Pennsylvania are very good as they are now.”

Rozzi was offered VIP passes to attend Pope Francis’ Philadelphia visit, but he turned them down.

Rozzi’s bill is one of three to expand the rights of victims that the state’s Catholic leaders, led by Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput, have successfully lobbied against.

State Rep. Ron Marsico, R-Dauphin, chair of the House Judiciary Committee where the bills have stalled, did not return a request for comment.

The Pennsylvania Catholic Conference, of which Chaput is governor, says the existing regulations are fair. The organization criticizes the window legislation because of the potential for stale evidence.

“Removing this fairness from our judicial system would make it impossible for any organization that cares for children to defend themselves in court years later,” wrote spokeswoman Amy Hill in a statement.

Chaput garnered national attention for his successful battle against similar bills in Colorado, when he served as Archbishop of Denver.

Advocates for reform believe that his track record there was the reason Chaput landed the top job in Philadelphia — a locus of the international clergy abuse scandal.

“The litigation industry, which especially focuses on suing Catholic institutions, is working to change the civil laws across the country and impose massive financial damages on Catholic and other private institutions — retroactively,” Chaput said in a 2006 newspaper interview during his stint in Denver. “They claim it’s about justice, but it’s very hard to see why it would be ‘just’ for innocent Catholic families today to have their community crippled because of the actions of evil or sick individuals 25 to 60 years ago.”

In 2009, two years after Delaware amended its statute of limitation laws, the Diocese of Wilmington filed for bankruptcy after it was named in more than 175 lawsuits.

Seeking truth and reconciliation

To Baselice, his fight to bring his son’s case to civil court has nothing to do with financial gain.

In 2004, when Arthur was in a treatment facility, a representative of Rev. Newman’s Franciscan order arrived to offer him $50,000 in exchange for signing a waiver that would relieve any additional liability from the order and the Archdiocese.

Arthur declined, but the priest persisted — at one point calling when the entire family was huddled around the phone.

“‘Just sign the release and you can do whatever you want with the money,'” Baselice remembers the priest telling his son.

“That’s what made me nuts,” he said. “My kid said, ‘But, Father, it’s not about the money. I want to get better.'”

Baselice sees the church’s current position as a continuation of what Philadelphia grand juries detailed in scathing reports published in 2005 and 2011: a church whose leaders systematically placed their organizational and financial self-interest ahead of the needs of sex abuse victims and the safety of other children.

“If I am successful in litigation. Is that check going to restore me? It’s going to punish them, but it’s not going to restore me. The only thing I can look for is a little bit of satisfaction,” said Baselice. “This all boils down to one word: truth. I’m trying to expose it. They’re trying to hide it.”

As that debate continues, advocates hope Pope Francis will use his international stage in Philadelphia to make a statement about clergy abuse.

Rumors suggest the pontiff may discuss the matter privately with a few victims, but the subject is not in the official public schedule for the World Meeting of Families.

Victims groups emphasize that many people in the region will be hurt by the week-long event.

“They are re-abused, re-wounded by this visit and the pomp and circumstance surrounding it when they’re still waiting for the person who hurt them — who raped them — to be put in jail,” said Karen Polesir, director of the Philadelphia chapter of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests.

In the wake of the clergy abuse scandal, which became widespread news in 2002, a few U.S. bishops resigned for their role in sheltering guilty priests, but the Vatican has not publicly disciplined any bishops for having protected sexual predators.

Advocates, though, were encouraged when Pope Francis announced in June the creation of a Vatican tribunal tasked with investigating and punishing bishops who covered up abuse.

Under Francis’ predecessors, Benedict and John Paul II, the church defrocked about 850 priests and penalized about 2,500 more for sexual abuse.

After the Philadelphia Grand Jury reports found that the actions of former Archbishops Cardinal Anthony Bevilacqua and Cardinal John Krol put children in harm’s way, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia says it made substantive reforms.

“The Church has recognized its mistakes and is dedicated to helping survivors heal, preventing abuse and protecting its people,” wrote spokesman Kenneth Gavin in an email correspondence. “The archbishop has also said that the lessons learned have made our church humbler, wiser and a more vigilant guardian of our people’s safety.”

Since 2006, the Archdiocese has provided more than $1.6 million in resources for counseling, medication, travel and childcare assistance, and other forms of support for survivors and their families.

It has also invested more than $2.4 million in education and training for adults and children to recognize and report abuse.

The Archdiocese paid for some of the younger Baselice’s medical treatment before he died. Over the years it has also funded therapy for Elaine and Ashleigh. Baselice Jr. turned down the offer.

As for the church’s larger reforms, Baselice is unmoved, and, for him, the hoopla surrounding Pope Francis’ visit is just too much to bear.

“I’m going to the islands for a couple of days just to get away from all this nonsense,” he said.

But no matter where he goes, Baselice says the pain of his son’s death will never leave him.

Standing in Arthur’s empty room, the father could do nothing but think of his own demise — pointing down to the last place he saw his firstborn child alive.

“If anything happens to me,” he said, “that’s the bed I’m dying in, right there.”

Kevin McCorry attended Archbishop Ryan High School from 1997-2001 while Rev. Charles Newman was principal. McCorry never had an interaction with Arthur Baselice III.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.