The upstart university, the beauty queen, and the future of higher ed

Listen

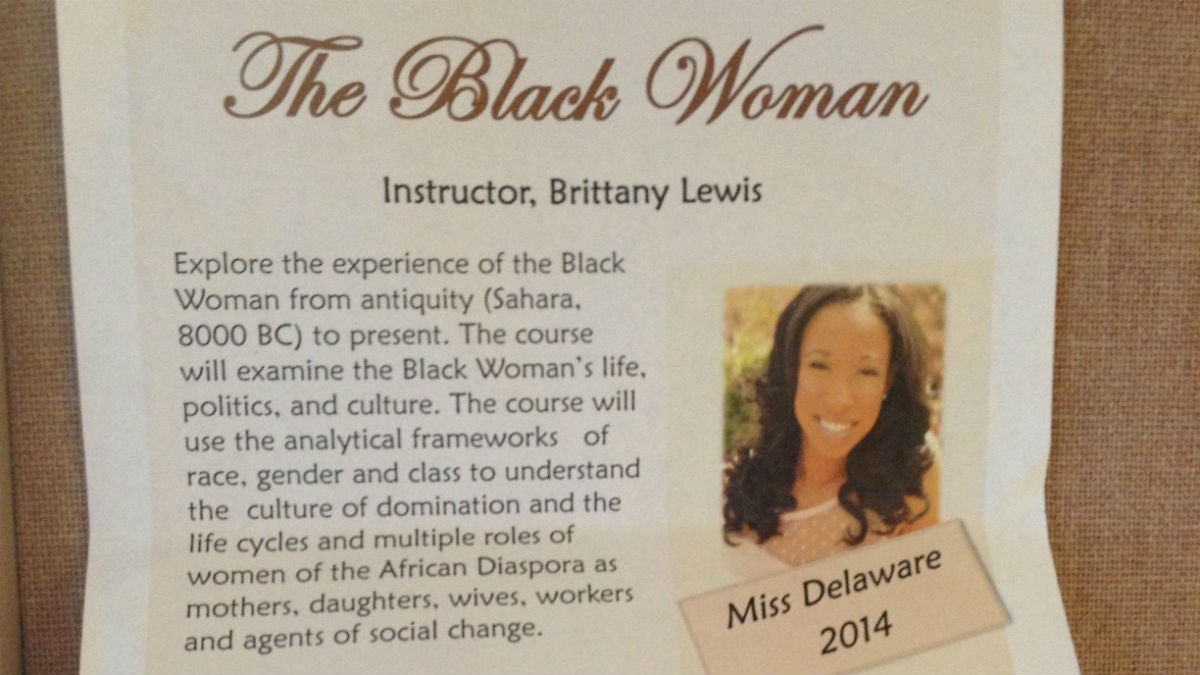

A flier for 'The Black Woman' at Wilmington University. (Avi Wolfman-Arent/for WHYY)

Last October Doreen Turnbo got an unusual message on her office voice mail.

“When I first heard it I have to confess I went, really, is this a joke,” Turnbo recalls.

The woman on the other end wanted to teach a college course. Turnbo, the dean of the college of arts and sciences at Wilmington University, wasn’t surprised by the offer. She was, however, surprised by the person making it.

“She left a message for me on the phone that said hello I’m Brittany Lewis, I’m Miss Delaware 2014,” Turnbo says. “I have an idea for a course and I would really enjoy talking with you about it and hope that you would consider allowing me to teach it.”

At a lot of four-year schools the story would stop here. A pageant champion wants to teach a credit-bearing course?

No thanks. Move along.

Turnbo had the opposite reaction. She and her team went right to work curating and approving the curriculum. “It really didn’t take very long at all,” Turnbo says. “I think maybe over two months we were able to flesh out what this course would look like.” By January, a course titled “The Black Woman” was being advertised to prospective students. By March, it was live.

Like that, Miss Delaware had become a college professor.

A changing professoriate

Lewis’ sudden transformation–without the benefit of a master’s degree or Ph.D. in the humanities–comes during a time of significant upheaval in the American professoriate. In 1975, full-time, tenure or tenure-track professors made up about 45 percent of all instructional staff, according to federal numbers crunched by the American Association of University Professors. Today that number hovers around 20 percent.

To replace them, colleges have dipped into a growing pool of part-time instructors and adjunct faculty who exist primarily to teach rather than conduct research. Many land at instructional schools like Wilmington University–schools committed to low overhead, limited bureaucracy, and career readiness.

At Wilmington, things go from idea to action fast, a strategy meant to keep the school relevant and responsive in a turbulent job market. That core belief in flexibility extends to the school’s faculty. Full-time professors with specific research interests can’t be deployed to meet, say, a booming demand for nurses. They are more or less fixed entities, and Wilmington University does not abide fixed entities.

“People outside of academia are our teachers,” Turnbo says. “They are our professional practitioners. And they are in every one of our colleges.”

The mere fact that Wilmington employs non-Ph.D.s is no surprise. Many schools hire “professors of practice” or “scholarly practitioners” to teach in pre-professional fields such as law, finance, and engineering.

At Wilmington, though, that hiring philosophy extends to every type of course–even those squarely situated in the humanities. Prior to winning Miss Delaware last year, Lewis had been a public school teacher. Before that, she studied African American history at Temple University. One of her primary qualifications for teaching a course on the “Black Woman,” however, was being a prominent a black woman.

“She fits the topic of the course,” Turnbo says.

Wilmington University by the numbers

Just 7.3 percent of Wilmington’s professors are full-time employees, according to the most recent federal data. That’s more than five times below the national average. To put that figure in perspective, Wilmington University (which is about to eclipse 20,000 total students) actually has 103 fewer full-time faculty than tiny Swarthmore College (enrollment 1500).*

That said, Wilmington University has zero graduate assistants. That means every course is taught by a professor. It also means that a lecture course listed under Professor Y’s name isn’t really being run by Professor Y’s teaching assistant. Wilmington also tends to hire professors with applicable full-time jobs. In other words, these aren’t starving adjuncts living gig-to-gig, but rather working professionals who teach on the side.

This malleable, adjunct-heavy workforce has allowed Wilmington to keep costs low and accommodate working adults and other so-called “non-traditional” college students. It’s also helped spur tremendous growth. Over the last 10 years, Wilmington University is the nation’s second-fastest growing private, four-year, Ph.D. granting university according to The Chronicle of Higher Education. Founded in 1968 on the site of a former motel, Wilmington now has more than 19,000 students at 14 locations throughout the region. Late last year, school officials announced the development of yet another campus, which will cover 29 acres in northern New Castle County.

“Wilmington University is not that motel school that we talked about 45 years ago or so,” says Jim Wilson, Wilmington’s Vice President for Academic Affairs. “It really is a regional leader in education.”

There is no one reason for this meteoric rise, but administrators say the school’s ability to streamline course creation and its willingness to hire faculty from outside the academy have been key. Both are hallmarks of a school that is “entrepreneurial at heart,” says Wilson. And they speak to a philosophy that chafes many in the higher education establishment–specifically, the notion that, as Wilson puts it, “Just because one has a doctorate doesn’t mean they necessarily know how to teach.”

They’ve “exploited an ecological niche”

John Barnshaw, a senior researcher at the American Association of University Professors, disagrees.

“There’s a lot of research that shows that faculty who are engaged in research actually are better able to explain the complex phenomena that you would get in a four-year education,” Barnshaw says.

Barnshaw used to live in Delaware–right across from a Wilmington University athletics complex, he says–and once directed the Delaware Cost Study, a proprietary survey service that allows universities to compare staffing strategies and costs. He argues that full-time faculty provide stability and force institutions to think big-picture about where they want to specialize.

“Institutions have to be strategic,” Barnshaw says. “And one of the best ways they can be strategic is making long-term commitments to high-quality faculty and giving those faculty the resources they need to excel in research and in teaching.”

Barnshaw acknowledges that Wilmington University and schools like it have been able to capitalize on huge spikes in the number of adults entering higher education, catering to a population traditionally ignored by research institutions. He believes, however, that the success is illusory. As online education expands the menu of educational options, Barnshaw believes schools with greater institutional focus–driven, naturally, by the research interests of their full-time faculty–will win out.

“If there was a high-quality Ph.D. instructor teaching intro to journalism at the University of Pennsylvania and they were to drop some of that content online they’re now directly competing with Wilmington University,” says Barnshaw. Wilmington University, he says, has “exploited an ecological niche very well. There’s nothing wrong with that, but there has to be an Act II.”

The question essentially is one of quality: Can a faculty full of part-timers and non-academics deliver a worthy college education?

Brittany Lewis certainly thinks so. She points out that she has a lot of the traits that make a good teacher. She’s a former Teach for America fellow. She’s used to speaking in front of strangers, thanks to her pageant experience.

An evening with Miss Delaware

In March, I dropped in on one of her classes. The topic was the history of black hair, and the students were discussing a serious academic text about black hair in the context of white oppression. Unlike many college seminars this course is actually lively–full of laughter, chatter, and testimony.

Nicole Evans, 34 and wearing scrubs, spoke about getting a perm as a child and how she had already, at a young age internalized this notion that her natural hair was somehow inadequate. “So when you have like a European person, right? They are born with how their hair is gonna be, right,” she says. “They don’t try to alter how their hair is gonna be.”

Evans, like a lot of the folks in this seminar, is what you’d call a “non-traditional” college student. Her dreams of higher education stalled when she got pregnant as a teenager. Now that her child is a teenager himself, Evans has gone back to school for her bachelor’s. Wilmington was the obvious choice.

“Wilmington University is inclusive,” she says. “They make it easy for you to get in the door, to take your placement test, to get approved to come into their programs. It’s just easier.”

Evans works as a nurse full-time, so Wilmington’s flexibility was key. She doesn’t care one bit that her teacher here isn’t a Ph.D. In fact, she really only has one gauge for educational quality. “I am tired. I came from work today. I had a million things to do when I got off of work,” she says. “But I was excited about coming to class. So that says a lot.”

She believes Brittany Lewis is a great teacher. And perhaps that shouldn’t be a surprise. Lewis really loves this material–loves it with the sort of passion you’d expect from a young, energetic academic.

In fact, she loves it so much that this fall she will start her Ph.D. in American history with a focus on black feminism at George Washington University.

Someday, Miss Delaware hopes to be a full-time, tenure-track professor.

*Wilmington University says it now has about 50 more full-time professors than reported by the federal government. It also claims the federal count of its part-time faculty is inflated and that at least some of those professors haven’t taught on campus in two or three years.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.